For better or worse, all I could think about when I travel by plane is kerosene, and the remarkable trick those mid-19th century inventors used to transform crude oil: distillation.

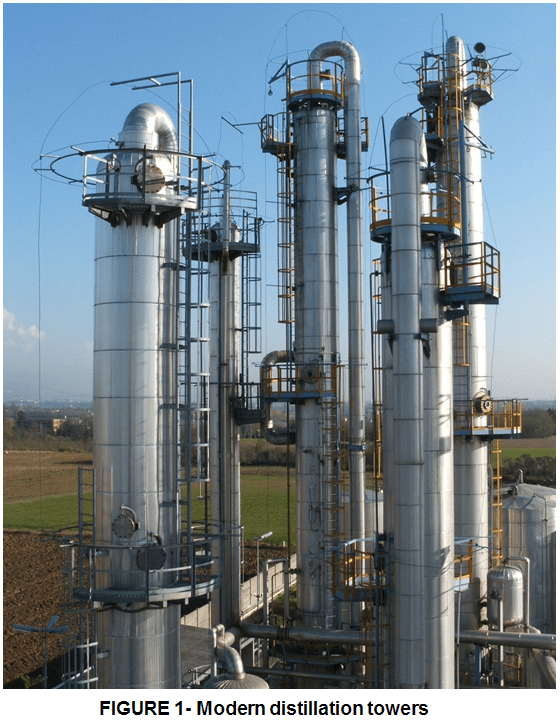

The story of Kerosene started many centuries ago. The Persian physician and alchemist Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Rizi also known as Rhazes, who lived roughly between 865 CE and 930 CE, wrote about his discovery of kerosene in his 9th-century Book of Secrets. Rhazes became interested in the naturally occurring springs of the region, which oozed not water, but a thick, black, sulphurous liquid. At the time, this tar-like material was extracted and used on roads, essentially as an ancient form of asphalt. Rhazes developed special chemical procedures, which we now call distillation, to analyze the black oil. He heated it up and collected the gases that were expelled from it. He then cooled these gases down again, whereupon they transformed back into liquid. The first liquids he extracted were yellow and oily, but through repeated distillation they became a clear, transparent and free-flowing substance – Rhazes had discovered the early form of kerosene. In order to distill oil, Rhazes had used an apparatus called an alembic, which is what, in modern times, we call distillation vessels – the towers you see sticking up out of oil refineries.

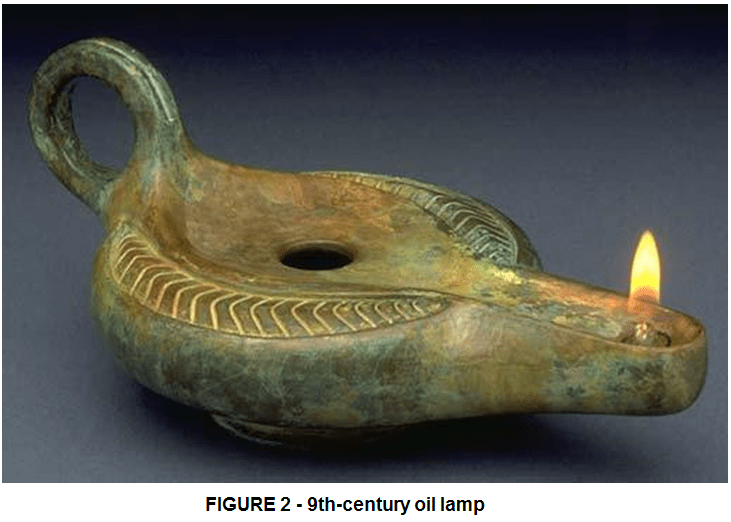

In the meantime, oil lamps evolved. The design of a 9th-century oil lamp looks simple, but it is remarkably sophisticated (FIgure 2 below) Think about a bowl of olive oil. If you simply try to light it, you’ll find it’s quite difficult. It’s hard because olive oil has a very high flashpoint. The flashpoint of a flammable liquid is the temperature at which it will spontaneously react with the oxygen in the air and burst into flames; for olive oil this is 315°C. That’s why cooking with olive oil is so safe. If you spill it in your kitchen, it’s not going to ignite. Also, to fry most foods you only need to get to a temperature of around 200°C, which is still a hundred degrees below olive oil´s flashpoint, so it’s easy to cook without the oil burning. But at 315°C, your pot of olive oil will burst into flames, and in doing so, will create a lot of light. Not only is this incredibly dangerous, but the flames will be short-lived; they´ll consume all the fuel very quickly. Surely, you must be thinking, there’s a better way to burn olive oil for light. And as it turns out, there is. If you take a piece of string, submerge it in the oil, leaving the top poking above the surface, and then light it, a bright flame is created at the tip of the string without having to heat up the full pot of oil, It is not the string that creates the flame; it is the oil emerging from the string. This is ingenious, but it gets better. If you continue to let it burn, the flame doesn’t travel down into the oil- instead the oil climbs up the string, only igniting when it gets to the top. This system can maintain the flame for hours; indeed, for as long as there is oil in the bowl. It’s a process called wicking, and seems miraculous – the oil is able to defy gravity and move autonomously – but it’s a basic principle of liquids and it´s possible because they possess something called surface tension.

Without wicking, candles wouldn’t work. When you light the wick on a candle, the heat melts the wax and creates a pool of molten wax.This liquid wax travels up the wick, through microchannels, to the flame. Thus feeding the flame with a new supply of liquid wax to burn. If you choose the right material for the wick, the flame will burn hot enough to maintain a pool of liquid wax, and ensure a constant flow of fuel. This deceptively complex system is self-regulating, and requires so little input from us we no longer regard candles as a piece of technology, but that is exactly what they are.

For thousands of years, all across the globe, wicking provided the primary mechanism for indoor lighting, whether in candles or oil lamps. Without these two technologies, at night the world descended into a dark gloom. As you might expect, oil lamps were popular in places where oils were plentiful, while candles were used where wax or animal fat were more readily available. Nevertheless, as ingenious as they were, candles and oil lamps had their drawbacks: there was obviously the fire risk, but there were also the production of soot, the low brightness of the flame, the smell and the cost. These shortcomings meant that there were always those searching for better and cheaper and safer ways of providing indoor light. Rhazes’ discovery of kerosene in the 9th century would have been the solution, had anyone realized it.

Lack of oxygen was a problem for ancient oil lamps too. The design didn’t allow enough oxygen to get to the fuel to burn it fully, which is why the flame gave off relatively low light. This was a problem right up until the 18th century, when a Swiss scientist named Ami Argand invented a new type of oil lamp that used a sleeve-shaped wick protected by a transparent glass shield. It was designed so that air could pass through the middle of the flame, radically improving the amount of oxygen delivered and thus the efficiency and brightness of oil lamps, making them equivalent to 6 or 7 candles.

This innovation led to many more, and eventually it became clear that olive oil and other vegetable oils were not ideal fuels. To get brighter light you need higher temperatures and for that you need faster wicking, and the speed of the wicking is determined by the surface tension and the viscosity of the liquid. Trying to find oils that were cheap but also had a low viscosity led to more experimentation, and, sadly, the deaths of a lot of whales.

Whale oil is produced by boiling strips of whale blubber. The oil the blubber releases is a clear honey colour. It’s not great for cooking or eating because of its strong fishy taste, but with a flashpoint of 230°C and low viscosity, it is very good for oil lamps. The use of whale oil in Argand lamps skyrocketed in the late 18th century, especially in Europe and North America. Between 1770 and 1775 the whalers of Massachusetts produced 45,000 barrels of whale oil per year to meet the demand. Whaling became a big industry, fueled by the need for indoor lighting, and some whale species were almost driven to extinction by that demand. It’s estimated that by the 19th century more than a quarter of a million whales had been killed for their oil. This could not go on, and yet the demand for indoor lighting was still on the rise.

As human populations grew bigger and wealthier, education became more important, the culture of reading and entertaining after dark became more prevalent, and so the demand for oils increased, as did the pressure on inventors and scientists to come up with ways to meet this need. Among them was James Young, a Scottish chemist who, in 1848, found a way to extract a liquid out of coal that had excellent properties for burning in an oil lamp. . Young called his liquid paraffineoil. A Canadian inventor, Abraham Gesner, did the same thing and called his product kerosene.

Crude oil is a mixture of differently shaped hydrocarbon molecules, some long like spaghetti, some smaller and more compact, others linked together in rings. The backbone of each molecule is made of carbon atoms, each one bonded to the next. Each carbon atom also has 2 hydrogen atoms attached to it, but there’s a lot of variety in their shape and size: the molecules vary in size from just 5 carbon atoms to hundreds. There are very few hydrocarbon molecules with fewer than 5 carbon atoms, though, because molecules that small tend to exist as gases: they’re called methane, ethane, propane and butane. The longer the molecule, the higher its boiling point, so the more likely it is to be a liquid at room temperature.

This is true of hydrocarbon molecules made up of up to 40 carbon atoms. If they get any bigger than that they can hardly flow at all and so become a tar. In distilling crude oil, the smaller molecules are extracted first. Hydrocarbon molecules with 5-8 carbon atoms form a clear transparent liquid which is extremely flammable: it has a flashpoint of -45°C, which means that even at sub-zero temperatures it will ignite easily. So easily, in fact, that putting this liquid into an oil lamp is quite dangerous. Thus, in the early days of the oil industry, it was discarded as a waste product. Later, when we began to better understand the virtues of this liquid, it became more appreciated, especially for the way it mixed with air and ignited, producing enough hot gas to drive a piston. It was subsequently named petrol (or gasoline), and we began using it to fuel petrol engines.

Larger carbon molecules, with 9-21 carbon atoms, form a transparent clear liquid with a higher boiling point than petrol. It evaporates at a slow rate and so is less easy to ignite. But because each molecule is quite big, when it does react with oxygen it gives off a lot of energy, in the form of hot gas. It won’t ignite, however, unless it’s sprayed into the air, and it can be compressed to a high density before it bursts into flames. This is the principle Rudolf Diesel discovered in 1897 eventually giving his name to the liquid forming the basis of his tremendous invention: the most successful engine of the 20th century. But in the early days of the oil industry, the mid-19th century, diesel engines hadn’t been invented yet, and there was a pressing need for a flammable substance for oil lamps.

While searching for this oil, producers created a liquid that had carbon molecules with 6-16 carbon atoms. This liquid is somewhere between petrol and diesel. It has the virtues of diesel – it doesn’t evaporate so quickly as to form explosive mixtures – but it is a fluid with a very low viscosity, similar to that of water. As a result it wicks extremely well, allowing flame to be very bright. It was cheap and effective, and didn’t rely on olive trees or whales. It was kerosene, the perfect lamp oil.

These discoveries might not have come too much, but, as it turned out, they just preceded the beginning of the American Civil War. Whaling ships became military targets, and taxes on other lamp oils created an opportunity for this new kerosene industry to find a foothold. But it didn’t really take off until inventors started playing around not with coal, but with the black oil that would be found near coal mines. This crude oil, which had to be pumped out of the ground, is a black, smelly, sticky substance. But before they could use it they had to harness distillation, an old trick first used for this by Rhazes – which proved to be extremely lucrative. Now the genie really was out of the lamp.

Today kerosene is a versatile fuel that is used for various applications and industries to provide predominantly heat, and also light and power. The most common type is aviation fuel. As the name implies, it is used to fuel and lubricate aircraft and other flying equipment. There is also rocket kerosene. Its features consist in chemical stability and a minimum amount of impurities in the composition. Many military jet fuels are blends based on kerosene as well. It can also be used as a refrigerant for heat exchangers. The level of wear resistance and low-temperature characteristics are the main advantages of this type of fuel.These advantages make it the cleanest type of fuel. The reverse thrust from the energy carrier is quite high, as well as the specific heat of combustion, which makes it possible to use it in rockets.

Kerosene is often used in the entertainment industry for fire performances such as fire-breathing, fire juggling or poi and fire dancing. Because of the low flame temperature, there is less risk of the performer coming into contact with the flames when burning outdoors.Various other used include:

- medical sphere (for lice removal, for lung treatment, for stomach therapy, for treatment of cardiovascular diseases and nervous system)

- clothing cleaner, impregnation of natural leather;

- lubricant for machine tools and apparatus;

- cooking fuel for portable stoves

- in some parts of the world, particularly in areas where the temperatures fall below freezing, kerosene is used as fuel in some types of diesel engines. It is less commonly used as fuel for ground transportation, although it has been used in the past for this purpose too;

- for burning in kerosene lamps and domestic heaters or furnaces

- as a solvent for greases and insecticides

- it’s very popular in properties with no gas mains connections as a way of fueling boilers

One of the main advantages of kerosene is considered to be its environmental safety. This type of fuel emits a small volume of vapor in the form of paraffin, so it is cleaner than wood or coal. But it also emits toxic substances, in particular, nitrogen and sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, etc. These elements can be harmful to the body if inhaled. It is better to use this fuel outdoors or in ventilated buildings.

Global civilization currently burns approximately one billion litres of kerosene per day, mostly in jet engines and space rockets, but it is also still used for lighting and heating in many countries. In India, for instance, more than 300 million people use kerosene oil lamps to provide lighting in their homes.

Wow! Great read! Very interesting and educational. I wish text books were written like this.

LikeLike

Thank you very much. I am glad you’ve enjoyed reading this. I also enjoy writing about materials science, this being one of the main reason why I created this blog. But one day who knows… probably I will publish my own text book about materials too, I will think about it. 🙂

LikeLike

Your communication style beautifully captures your authentic self, making readers feel engaged and heard.

LikeLike

I’m glad you like it, thanks for reading ;-).

LikeLike

I just put there things simply as they are without much scientific terms. I am glad to know you enjoy my content. Thank you so much.

LikeLike