I love to talk about Copper. I must say that before to become materials science engineer I was very much in touch with electronics and initialy I wanted to become electronics engineer but it was Copper the metal that fascinated me since the beginning when I created my first PCBs for my electronic circuits. So indeed Copper is a remarcable metal. During my years at the techincal university I had the opportunity study Copper even more, the amout to details here is huge. I will cover few of them in this post. I consider to write more posts about Copper becasue this metal has a lot to offer. But let me start with its most important characteriscis. So WHAT is COPPER?

THE RAW METAL

The Beginnings of Bronze

The story of copper and its principal alloys, bronze (Cu-Sn) and brass (Cu-Zn), is virtually a chronicle of human endeavor since man emerged from the Stone Age. The ubiquity of the copper metals and their contribution to every civilization since Sumeria and Pre-Dynastic Egypt gives them a unique position in the history of technology.

Copper is one of those 6 metals that man started using very early. As a matter of fact, copper was the first metal that man discovered in 10.000 years ago. The other 5 metals used in pre-historic times were gold (Au), silver (Ag), tin (Sn), lead (Pb), and iron (Fe).

The earliest definite date usually assigned to true bronze casting is about 2500 B.C., i.e. 700 years or more after copper is known to have been in use; nevertheless numerous analyses show that copper artifacts of around 3000 B.C. sometimes contain small and variable percentages of tin (Sn). These may be regarded as “accidental bronzes.” One of the first things that the early coppersmith must have learned was that when he hammered copper he hardened it and, conversely, by heating the object he could soften or anneal it again. Thus the unalloyed metal could be fabricated and cut in a number of different ways. But when some unknown inventor conceived the idea of deliberately adding fixed proportions of tin (Sn) ore to the melt, he produced true bronze and thereby started the Bronze Age. As bronze was harder, almost equally durable and decidedly easier to cast than copper, although much more liable to fracture if not properly made, its use spread rapidly. In the Mediterranean countries bronze was not supplanted for over 2000 years and it lasted a good many centuries longer in north-western Europe, where methods of extracting and working iron were slower to follow those of Hallstadt and Rome. Meanwhile, both bronze and copper ran side by side. Museum labels on exhibits are not to be trusted unless analyses have been made and it is only in recent years that this has been systematically undertaken.

The majority of the surviving relics of early copper work are in cast form, an art which the Egyptians quickly brought to a high state of perfection. It is less easy to cast copper than bronze; but once they had learned to alloy the metal deliberately with tin, and frequently also with a little lead, the operation became much easier. When a little tin (Sn) or lead (Pb) is added, even accidental amounts like 1%, the production of sound castings becomes much easier; and this must have hastened the development of bronze as a definite alloy.

The melt flow was improved, and thereafter there was no limit to their fertility of invention. In this connexion, it must be remembered that the abundant remains, which the world possesses today, are but a fraction of what once existed in Egypt, the rest having been stolen or melted down and recast into other forms.

Small, decorative pendants and other items discovered in the Middle East have been dated about 8700 B.C. These objects were hammered to shape from nuggets of “native copper,” pure copper found in conjunction with copper-bearing ores. The earliest artifacts known to be made from smelted metal were also copper. These were excavated in Anatolia (now Turkey) and have been dated as early as 7000 B.C. The discovery of a copper-tin (Cu-Sn) alloy and its uses led to the Bronze Age, which began in the Middle East before 3000 B.C. More recent discoveries in Thailand, however, indicate that bronze technology was known in the Far East as early as 4500 B.C. The Bronze Age ended about 1200 B.C., after which iron technology (the Iron Age) became common.

The Beginnings of Brass

The Romans were the first to use brass on any significant scale, although the Greeks were well acquainted with it in Aristotle’s time (c. 330 B.C.). They knew it as ‘oreichalcos’, a brilliant-and-white copper, which was made by mixing tin (Sn) and copper (Cu) with a special earth called ‘calmia’ that came originally from the shores of the Black Sea. Pure zinc was not known until quite modern times, the ore employed being calamine which is an impure zinc carbonate rich in silica. The earliest brass was made by mixing ground calamine ore with copper and heating the mixture in a crucible. The heat applied was sufficient to reduce the zinc to the metallic state but not to melt the copper. The vapour from the zinc, however, permeated the copper and formed brass which was then melted.

Some Roman armour, particularly the helmets worn on ceremonial occasions, was made of brass. A large number of fine specimens of these helmets still survive. Spears and swords, daggers and palstaves, were originally of bronze, but later for weapons the Romans turned entirely to iron. The Romans also used brass for brooches (fibulae), personal ornaments and for decorative metalwork. The alloys employed contained from 11 to 28% Zinc, and the Romans clearly knew the value of different grades of brass for different purposes. The quality specified for delicate decorative work, for instance, had to be very ductile and of a good colour; and the Roman mixture contained about 18% Zinc and 80% Copper, i.e. it was about the same as the modern ‘gilding metal’ so widely used today for imitation gold jewellery.

The Major Groups of Copper and Copper Alloys

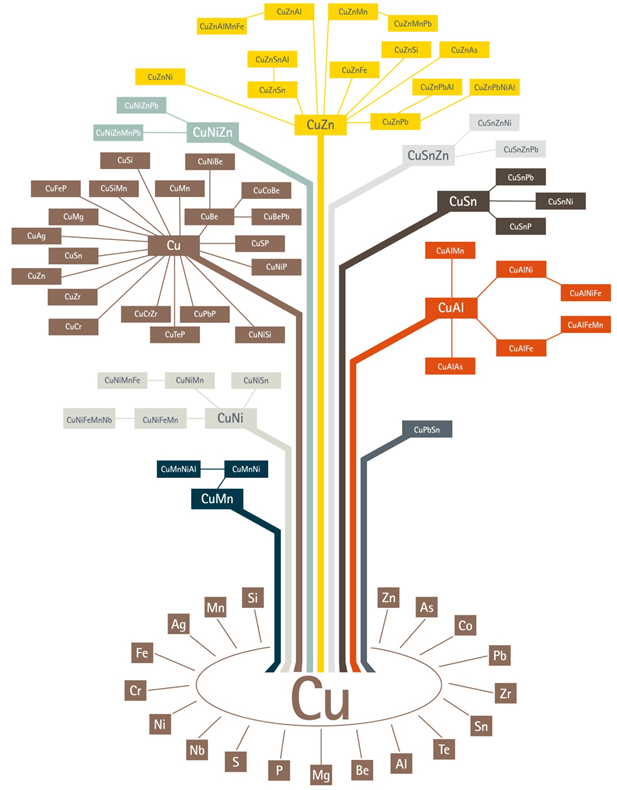

The elements most commonly alloyed with copper are aluminum (Al), nickel (Ni), silicon (Si), tin (Sn), and zinc (Zn). Other elements and metals are alloyed in small quantities to improve certain material characteristics, such as corrosion resistance or machinability. Copper and its alloys are divided into 9 major groups. These major groups are:

- Coppers – Cu, which contain a minimum of 99.3% Cu

- High-copper alloys – High Cu, which contain up to 5% alloying elements

- Copper-zinc alloys Cu – Zn (brasses), which contain up to 40% Zn

- Copper-tin alloys Cu- Sn (phosphor bronzes), which contain up to 10% Sn and 0.2% P

- Copper-aluminum alloys Cu-Al (aluminum bronzes), which contain up to 10% Al

- Copper-silicon alloys Cu-Si (silicon bronzes), which contain up to 3% Si

- Copper-nickel alloys Cu-Ni, which contain up to 30% Ni

- Copper-zinc-nickel alloys Cu-Zn-Ni (nickel silvers), which contain up to 27% Zn and 18% Ni

- Special alloys, which contain alloying elements to enhance a specific property or characteristic, for example, machinability

Production of Copper

Primary copper is produced from sulfide copper minerals and oxidized copper minerals. These materials are processed pyrometallurgically and/or hydrometallurgically to produce a high-purity electrorefined or electrowon copper containing less than 40 parts per million (ppm) impurities, which is suitable for all electrical, electronic, and mechanical uses. Secondary copper is produced from recycled scrap. Recycling of scrap accounts for approximately 40% of copper production worldwide.

The Industrial Revolution brought about a tremendous change in the production of copper and its alloys. In the first place, an insistent demand arose for more and better raw material. Therefore from mid of 18th century the copper has literally put humanity again in another copper Age: The Electrical Age and one more time today in the Digital Age. The technology we have today would have not been possible without Copper.

As the biggest technological milestones ever made by humans because of Copper, I would mention:

- The Invention of the Stamping Press (which inevitably was followed by coining presses)

- The Navigational Instruments

- The Brass Clocks and Watches

- The Architecture and the Fine Arts

- The Shipbuilding

- The Lightning Conductor

- The Voltaic Pile and its Consequences

- The electrical transformer

- The electromagnets and the electric motor

- The Dynamo

- The Electric Telegraph

- The Submarine Cables & The Atlantic Cable

- The Cables & The Electricity Generation and Supply

- The Telephone

- The Electric Lighting

- The Radio and The Radar

- The Modern Architecture, Building and Plumbing

- The Railways and Other Traction on Land

- Money

- The Paper Manufacture

- Printing (of books, magazines, photographs)

- The Printed Circuit Boards

- The large brewing vats

- The compounds and fertilizers for Agriculture and Horticulture

Just to name the few of them, all these applications were only possible because of Copper. Thus, in the 20th & 21st Century we have turned the complete circle. Industry began with man, the agriculturist, picking up shining pieces of copper and wondering what they were; and we conclude with man, the horticulturist, putting back the same element in solution out of a watering-can. The modern Agriculture depends very much on Copper.

We need COPPER more than ever. This metal is just super useful.

I’m always amazed by the depth of research that goes into your blog posts.

LikeLike