Carbon is a marvel of nature. This element is absolutely impressive. First of all Carbon is the main reason why life on Earth exist. And second because carbon is capable of forming the most compounds , way much more than all the other elements in Periodic Table combined. Not only that but Carbon is even able to bond with itself creating many allotropes (structurally different forms of the same element) due to its valency. Now this is not really unique only to carbon, of course there are other elements which bond with themselves creating allotropes, like for example tin (Sn) or Phosphorus (P). Yet Carbon is special, nanotechnology is overwhelmingly carbon-based and carbon allotropes play an essential role for future technology developments. They’re all pure carbon but with different arrangements of their atoms. Let’s take a look at a few of these from a more human scale

Well-known forms of carbon include of course: the diamond and the graphite. But in recent decades, many more allotropes have been discovered and researched including:

- ball shapes such as buckminsterfullerene

- sheets such as graphene.

- larger scale structures of carbon also include nanotubes, nanobuds and nanoribbons.

- other unusual forms of carbon exist at very high temperatures or extreme pressures.

According to the Samara Carbon Allotrope Database (SACADA) there are around 500 hypothetical 3-periodic allotropes of carbon known at the present time and new ones are constantly being discovered or predicted.

Carbon has up to date, 15 isotopes from which only 2 are stable: Carbon-12 and Carbon 13. The rest of 13, are all radioactive and with few exceptions, most of these decay in matter of seconds. They are generally used for further scientific research. However if we put radioactivity aside, the nucleus plays a back-seat role in carbon. Any carbon atom has 6 protons in their nucleus and 6 electrons orbiting it. The most frequent carbon we deal with is Carbon-12.

In terms of all of its other properties and behavior it is the 6 electrons that surround and shield the nucleus that are important. 2 of these electrons are deeply embedded in an inner core near to the nucleus and play no role in the atom’s chemical life – its interaction with other elements. This leaves 4 electrons, which form its outermost layer, that are active. It is these 4 electrons that make the difference between the graphite of a pencil and the diamond of an engagement ring. To understand this we need to understand the basic models of how we visualize electron orbits around the nucleus of an atom.

HOW CARBON ATOMS COMBINE TO FORM COMPOUNDS

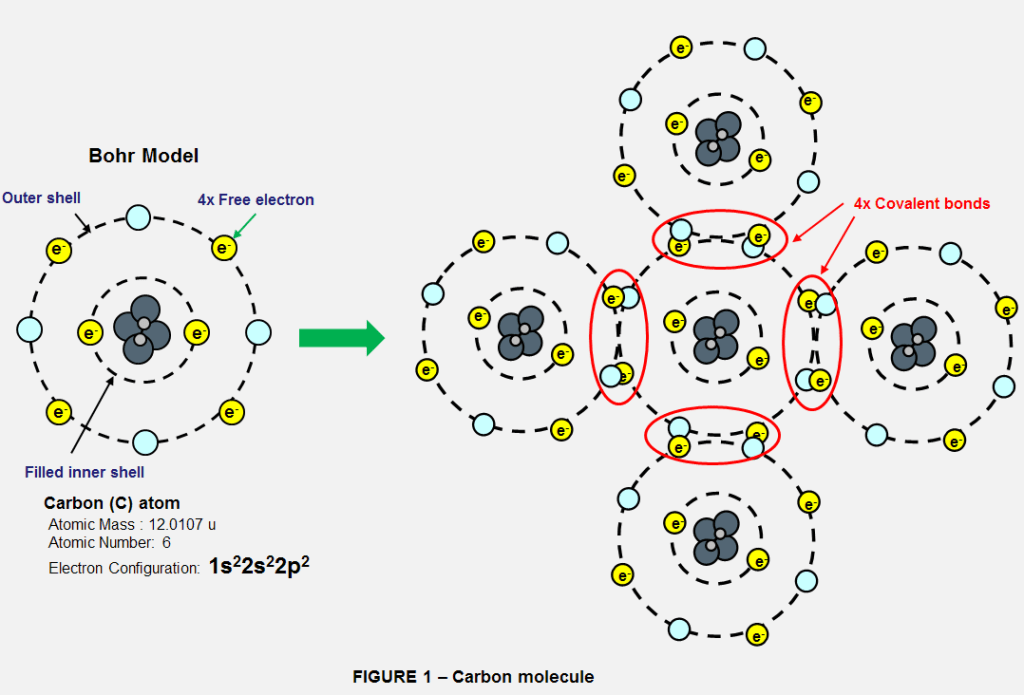

To start we have the simplified Bohr model, which separates the electrons into shells. The first shell can contain 2 electrons, while the next shell can hold 8. An atom wants to fill each shell to be stable. Let’s take an atom of carbon, which has 6 electrons, to see how this plays out.

First we fill the first shell with it’s 2 electrons, then we have 4 electrons left to fill the next shell, leaving 4 open positions in its outer shell. The 4 open positions mean that carbon willingly interacts with many other elements as well as itself. Often by sharing electrons in a special type of bond, called a covalent bond. This versatility allows carbon to create many different kinds of molecules.

A COVALENT BOND is = a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs, and the stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms, when they share electrons is known as covalent bonding.

Take hydrocarbons. These are molecules formed between Hydrogen (H) and Carbon (C) atoms. Hydrogen has 1 electron, and seeks 1 electron to fill it’s inner shell. So, carbon likes to form 4 covalent bonds with 4 hydrogen atoms to form a stable 8 electron outer shell, while helping hydrogen form a stable 2 electron shell. This is methane (CH4), an incredibly common molecule that is the main ingredient in natural gas fuels. This is just one example of arrangement carbon can take.

Hydrocarbons take a huge range of shapes and configurations, but what we are interested in is how carbon bonds to itself. This simplified Bohr model doesn’t give us a clear understanding of how carbon to carbon bonds take radically different shapes.

HOW CARBON ATOMS COMBINE WITH THEMSELVES TO FORM ALLOTROPES.

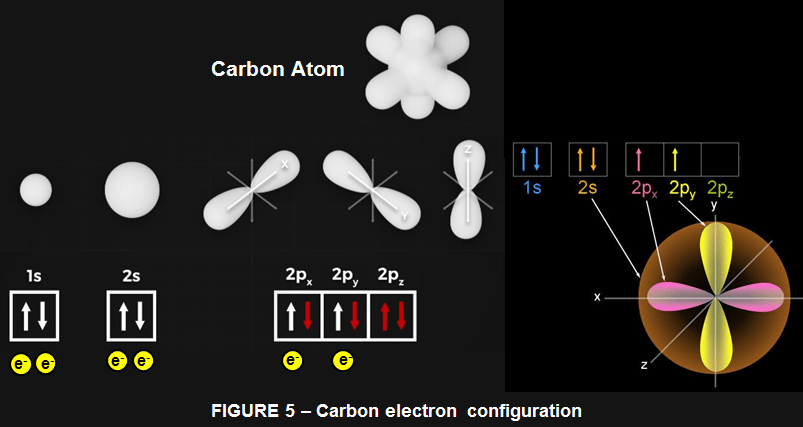

To have a better picture, we need to dive a little deeper before we can understand the magic of carbon allotropes (such as carbon nanotube, fullerene, diamond, graphene etc.). Electrons don’t travel in neat 2D circular orbits as the Bohr model would suggest, in fact we can’t even know the position and speed of an electron. Instead we can make predictions about electrons’ general locations in 3D space. We call these orbitals, and they are regions where we have about a 90% certainty that an electron is located somewhere within that region. A neutral carbon atom has 6 electrons, which are arranged in a ground-state electron configuration of: 1s22s22p2 . This means that :

- 1s orbital: Holds two electrons.

- 2s orbital: Holds two electrons.

- 2p orbitals: Holds the remaining two electrons, with each electron occupying a separate 2p orbital (e.g.,2px and 2py) to minimize repulsion

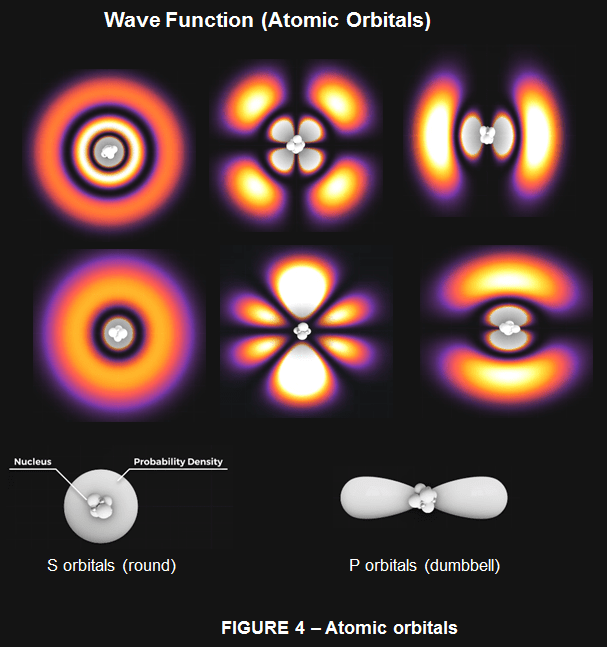

However, in bonding, carbon’s orbitals tend to merge (hybridize) to form new orbitals (sp3,sp2 or sp) with different shapes, energies, and spatial arrangements that allow it to form 4 covalent bonds. Like that electrons are shared more regularly around the nucleus and provide some interesting opportunities to form bonds with other atoms. This can get pretty complicated, but for now we just need to concern ourselves with two types: s and p orbitals.

s orbitals are spherical in shape with the nucleus of the atom at their centre. p orbitals are often called dumbbell shaped, in fact it’s more like a figure of 8 shape like the infinity symbol. (As shown in Fig 4). In the ground state, electrons will occupy the lowest energy orbitals first, which in this case is the 1s orbital. It can hold 2 electrons.

Next we have the 2s orbital, which is a larger sphere, and can also hold 2 electrons. Then we have our three p orbitals, one aligned along the x, y and z axis, each capable of holding 2 electrons. Carbon in its ground state has the 1s and 2s orbitals filled, with 1 electron in the px orbital and 1 in the py orbital. To be stable, Carbon wants to fill these 3p orbitals with 2 electrons each. Now this where things get a little funky and confusing. Carbon can bond to itself in different ways that affect these orbital shapes.

Take diamonds. = To fill these orbitals, carbon bonds with 4 neighboring carbon atoms. To do this it promotes one electron from it’s 2s orbital into the empty pz orbital. This pz orbital is higher energy than the 2s orbital, and the electron doesn’t want to stay there, so the carbon atom takes on new hybrid orbital shapes to compensate. This is called sp3 hybridization, which is a mixture of s and p orbital shapes and looks something like as shown in Fig. 6.

Where one side of the figure of dumbbell expands, while the other contracts. The 2s and 3p orbitals are transformed into 4 new sp3 orbital shapes. They repel each other equally a 3D space to form a 4 lobed tetrahedral shape with 109.5 degrees between each lobe. Covalent bonds now form between the carbon molecules where these orbital lobes overlap head on in what’s called a sigma bond.

This creates a repeating structure like this and it’s this rigid framework of carbon atoms that makes diamond extremely hard.

Now, what’s fascinating to me, is that you can take the same carbon atoms and now form graphite, a material so soft that we use it as pencil lead and as a lubricant. How does that work?

For Graphite a different hybridisation occurs. Once again 1 electron from the 2s orbital is promoted into the pz orbital, but this time the s orbital hybridizes with only 2 of the p orbitals, giving us the name sp2 hybridization.This gives us 3 sp hybrid orbitals and 1 regular p orbitals.

This new arrangement causes the orbitals to take a new shape, with the 3 sp orbitals arranging themselves in a flat plane separated by 120 degrees, with the p orbital perpendicular to them. Now, when the carbon atoms combine, the heads of the sp orbitals overlap once again to form this flat hexagonal shape.

A hexagon pattern is naturally a very strong and energy-efficient shape. For example, bees don’t intentionally build honeycombs in hexagons They form as a result of the warm bee bodies melting the wax and the triple junction hardens in the strongest formation.

The shape is frequently used in aerospace applications where high strength and low weight is a priority.

FEW OF THE MOST FREQUENT CARBON ALLOTROPES

AMORPHOUS CARBON/COAL = when carbon atoms join willy-nilly with no orderly structure we have amorphous carbon. This is the main carbon allotrope we encounter usually found in coal and soot.

DIAMOND= is a manifestation of carbon in its purest form. This is one of the most ordered arrangement of carbon atoms where every atom is connected to 4 other atoms in a tetrahedral succession of crystalline arrangements by very strong covalent bonds. All electrons are involved in these bonds, which makes diamond an extraordinarily hard and strong material. Likewise it comes transparent because there are no free electrons to absorb the light that passes through it.

LONSDALEITE = this is another ordered arrangement which is a rare form of diamond. Is the hardest solid known, almost 60% harder than normal diamonds.

GRAPHITE = in graphite the atoms are arranged in a semi-crystalline structure in hexagonal flat sheets with very weak atomic bonds between the sheets. Each carbon atom is bonded to 3 others, forming planes. There is 1 spare electron per atom, which allows it to delocalize and break free from its atom. The existence of free electrons means that graphite is conductive and opaque with a shiny almost metallic sheen.

GRAPHENE = is closely related to graphite, yet this is the equivalent of an extremely well-ordered thin layer of graphite, made to have only a single sheet of atoms. It’s an ordered arrangement in which the carbon atoms are arranged in hexagonal rings along a wide plane. It’s a 2D shaped material.

FULLERENES = These are molecules formed solely by carbon atoms, joined in hexagonal and pentagonal rings. These are usually molecules with 60 and 70 carbon atoms arranged in a spherical/dome-shaped form of carbon structures, named after Buckminster Fuller the american architect who popularized the geodesic dome.

CARBON NANOTUBES = lastly you can roll a graphene sheet into a tube and you get carbon nanotubes. Carbon nanotubes are generally a handful of nanometers (10-9m) wide, but can reach several millimeters in length. They are remarkably strong and have interesting electrical properties. Both Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene play an important role in the future of electronics and materials science.

Leave a comment