Chocolate is not food. Chocolate is a material. You can create things out of chocolate exactly like you do with any other material such as plastic, metal, glass, wood, ceramics or concrete. Except that chocolate is the only one material which is delicious. It is a soft material with good enough mechanical strength, is quite easy to work with it and create objects. After you finish building your chocolate object if you really want, you can also eat it.

Chocolate starts with Cocoa beans. These beans must be processed in multiple stages until we get the final product as raw chocolate. Basically the general process of how all chocolate is made is this:

STEP 1

While still on the Cocoa tree, the pods start out green and turn orange when they’re ripe. Then, when the pods are ripe, harvesters travel through the cocoa orchards with machetes and hack the pods gently off of the trees.

STEP 2

Cocoa needs to be harvested manually in the forest. That’s simply because, machines could easily damage the tree or the clusters of flowers and pods that grow from the trunk, so that’s why workers must harvest the pods by hand.

STEP 3

The farmers cut the outer peel of the cocoa pods, open with long knives to collect the fruit pulp inside and then deposited them in a heap on the ground. This natural process removes any of the remaining fruit pulp around the beans.

STEP 4

Over 2 weeks the heaps of beans start to decompose and ferment, and in the process they heat up. During fermentation, the beans change from gray to brown to purple and develop their aroma.

If this step doesn’t take place, whatever else you do, you won’t get anything remotely like chocolate. It is during this fermentation that the fruity ester molecules are created, which is the result of a reaction between the alcohols and the acids that are created by enzymes acting within the cocoa beans. As with all chemical reactions there are a vast number of different variables that affect this outcome, such as:

- the ratio of the ingredients,

- the surrounding temperature,

- the availability of oxygen …and many others.

This means that the taste of chocolate is highly dependent not just on the ripeness and species of the cocoa bean, but also on how high the rotting piles of beans are stacked, how long they are left to rot and generally what the weather is like.

STEP 5

After fermenting, the cocoa beans are spread out and left to dry in the sun for about 6 days. This serves the purpose of “killing” the cocoa seeds, in as much as it stops them from germinating into cocoa plants. But more importantly it chemically transforms the raw ingredients of the cocoa bean into the precursors of the chocolate flavours.

After the cocoa pods are dry enough, they are collected into baskets, thousands of sacks of cocoa are taken from the collection centers to huge warehouses. The beans, packed in sacks or containers, are then shipped to the cocoa processing houses. Here they are split open and the cocoa beans are removed, then they are send to chocolate producing sites in Europe, America and Asia.

+++++++++++++++++++++

If all these make you wonder why chocolate makers rarely talk about these subtleties, it is because they are a secret. On the face of it cocoa seems to be like other commodities: a basic ingredient, like sugar, that is bought and sold on world makers, fueling a billion-dollar industry in edible products. But what is much less talked about is that, just like coffee and tea, different varieties of bean and different techniques of preparation create vastly different tastes. A detailed understanding of both is required to buy the right beans and when it comes to creating the finest chocolates this knowledge is closely guarded.

Controlling quality, meanwhile, also means taking into account the variability of tropical weather and the sporadic influx of disease. All in all, producing quality chocolate requires a huge amount of care and attention, which is why good dark chocolate is expensive. What you get for money, though, is not just the delicate fruity flavours from the fermented esters, but a set of earthy, nutty, almost meaty flavours. These are produced in the process that comes after fermentation, when the beans are dried and roasted. As with coffee making, roasting turns each bean into a mini chemical factory, in which a new set of reactions takes place.

First, the carbohydrates within the bean, which are mostly sugar and starch molecules, start to fall apart because of the heat. This is essentially the same thing that happens if you heat up sugar and starch molecules, start to fall apart because of the heat. This is essentially the same thing that happens if you heat up sugar in a pan: it caramelizes. Only in this case the caramelizing reaction takes place inside the cocoa bean, turning it from white to brown and creating a wonderful range of nutty caramel flavour molecules.

The reason why any sugar molecule – whether is a cocoa bean or a pan or anywhere else – turns brown when heated is to do with the presence of carbon. Sugars are carbohydrates, which is to say that they are made of carbon (“carbo-“), hydrogen (‘hydr-‘) and oxygen (‘-ate’) atoms. When heated, these long molecules disintegrate into smaller units, some of which are so small that they evaporate (which accounts for the lovely smell). On the whole, it is the carbon-rich molecules that are larger, so these get left behind and within these there is a structure called a ‘carbon-carbon double bond’.

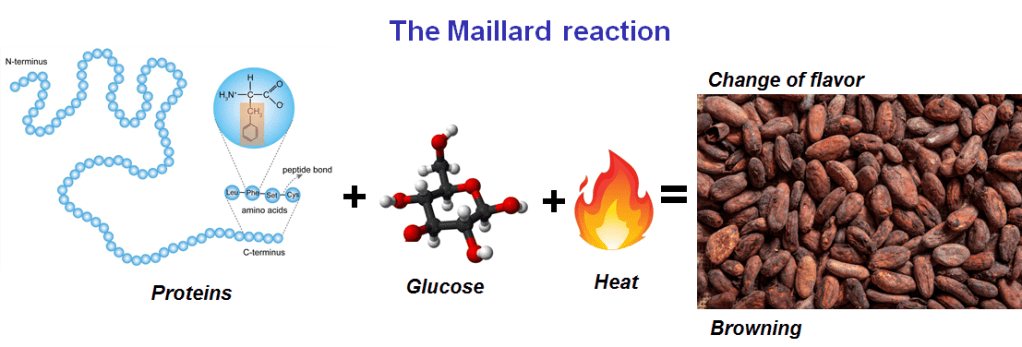

This chemical structure absorbs light. In small amounts it gives the caramelizing sugar a yellow-brown color. Further roasting will turn some of the sugar into pure carbon (double bonds all round), which creates a burnt flavour and a dark-brown color. Complete roasting results in charcoal: all of the sugar has become carbon, which is black. Another type of reaction, which occur at a higher temperature, also contributes to the colour and flavour of the cocoa: the Maillard reaction.

This is when a sugar reacts with a protein. If carbohydrates are the fuel of the cellular world, proteins are the workhorses: the structural molecules that build cells and all their internal workings. Seeds (in the form of nuts or beans) must contain all of the protein needed to get the cellular machinery of a plant up and running, so there is plenty of protein in the cocoa beans. When subjected to temperatures of 160°C and above, these proteins and carbohydrates start to undergo Maillard reaction, reacting with the acids and esters (produced by the earlier fermentation process) and resulting in a huge range of smaller flavour molecules.

It is no exaggeration to say that without the Maillard reaction the world would be a much less delicious place: it is the Maillard reaction that is responsible for the flavour of bread crust, roasted vegetables, and many other roasted, savoury flavours. In this case, the Maillard reaction is responsible for the nutty, meaty flavours of chocolate, while also reducing some of the astringency and bitterness.

Grind up the fermented and roasted cocoa nuts and add them to hot water and you have the original hot “chocolate” made by Mesoamericans. The Olmecs and then the Mayans, who 1st cultivated chocolate, drank in this way, and it was revered as a ceremonial drink and an aphrodisiac for hundreds of years. The cocoa nuts were even used as currency. When European explorers got hold of the drink in the 17th century, they exported it to coffee houses, where it competed with tea and coffee to be the beverage of choice of Europeans – and lost. What no one had really mentioned was that “chocolate” means “bitter water”, and even though it was sweetened with the new cheap sugar flooding in from the slave-run plantation of Africa and South America, it was also a gritty, oily and heavy drink, because 50% of the cocoa bean is cocoa fat. This is how it remained for another 200 years: an exotic drink, notable but not terribly popular.

Once the cocoa beans are processed as described above, we can continue the process with the next stage by making the basis ingredient for chocolate: THE COCOA BUTTER. When this is ready then you the finally you can make your chocolate.

COCOA BUTTER is one of the finest fats in the vegetable kingdom, slugging it out with dairy butter and olive oil for pole position. In its pure form it looks like fine unsalted butter and is the basis not just of chocolate but of luxury face creams and lotions. Don’t let this put you off – fats have always provided humans with more than just food, in the form of candles, creams, oil lamps, polish and soap. But cocoa butter is a special fat for many reasons.

For one, it melts at body temperature, meaning that it can be stored as a solid but becomes a liquid when it comes into contact with human body. This makes it ideal for lotions. Moreover it contains natural antioxidants which prevent rancidity, so it can be stored for years without going off (compare that to butter made from milk, which has a shelf life of only a few weeks). This is good news for face cream makers but also for chocolate manufacturers.

Cocoa fat has another trick up its sleeve: it forms crystals, and these are what give chocolate bars their mechanical strength. The major component of cocoa butter is a large molecule called a triglyceride, which forms crystals in many different ways, depending on how these triglycerides are stacked together. It’s a bit like packing the boot of a car: there are many ways to do it, but some take up more space than others. The more tightly packed the triglycerides, the more compact the crystals of cocoa fat. And the denser the cocoa fat, the higher its melting point and the more stable and stronger it is. These denser forms of cocoa are also the hardest to make.

Leave a comment