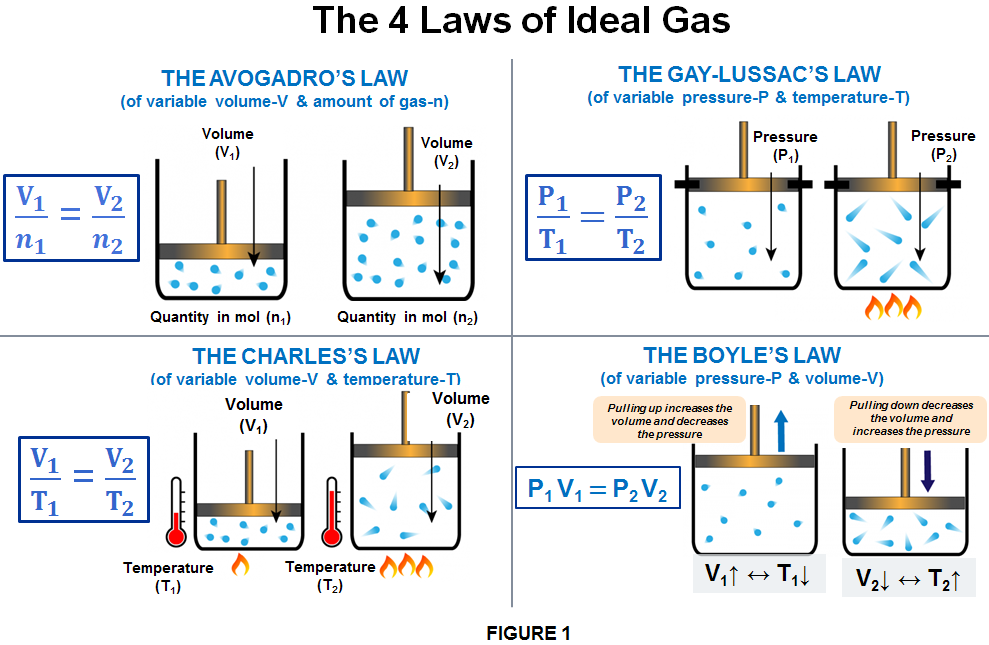

Gas is the 3rd state of matter which has nor fixed shape neither a fixed volume. However gases are essential for many applications. In order to study, understand and keep a gas under control, we need to have a good study reference as starting point. And we do have that. The behavior or gases is mainly characterized by the 4 gas laws. For a quick recall these are the 4 main gas laws:

- THE AVOGADRO’S LAW – of variable volume & constant amount of gas;

- THE CHARLES’S LAW – of variable volume & temperature;

- THE GAY-LUSSAC’S LAW – of variable pressure & temperature;

- THE BOYLE’S LAW -of variable pressure & volume.

These laws assume that all gases behave like an “ideal” gas. In such a gas, there are no interactions between individual gas particles, the particles move randomly, and they take up no space. Even though no real gas has these features, the gas laws do show how most gases behave at normal temperatures and pressures. Also, in calculations involving gases we must always consider the gas constant which is linked to the condition of ideal gas.

IDEAL GAS CONSTANT = The kinetic energy per unit of temperature of 1mole of a gas is a constant value, sometimes referred to as the Regnault constant (R), named after the French chemist Henri Victor Regnault. Studying the thermal properties of matter Regnault discovered that Boyle’s law was not perfect. He noticed that when the temperature of a substance nears its boiling point, the expansion of the gas particles is not exactly uniform. Therefore combining the 4 gas laws, Regnault calculated a new constant as the molar equivalent to the Boltzman constant expressed in units of energy per temperature increment per amount of substance, rather than energy per temperature increment per particle. He simply multiplied the Avogadro’s constant with Boltzman’s constant, the result being the constant R which we call the Ideal Gas Constant.

R = NA * k = 8.31446261815324 J K-1 mol-1

Taking all these observations into consideration, we can define more clearly what’s an ideal gas.

IDEAL GAS (or the Perfect Gas) = is the theoretical substance that helps establish the relationship of 4 gas variables, pressure (P), volume(V), the amount of gas(n) and temperature(T). In a more comprehensive description, the ideal gas has the following characteristics:

- In an ideal gas we assume that the gas particles are extremely small and hence their volume is negligible. So the gas does not occupy any spaces. The volume of the system is much larger than the volume of the gas atoms or molecules. The gas fills its container and has empty space between gas molecules. Than means they are expandable and compressible.

- Ideal gases do not experience any intermolecular forces between gas particles. Particles are in constant motion and they only collide elastically with each other and with the walls of container. So their kinetic energy is fully conserved.

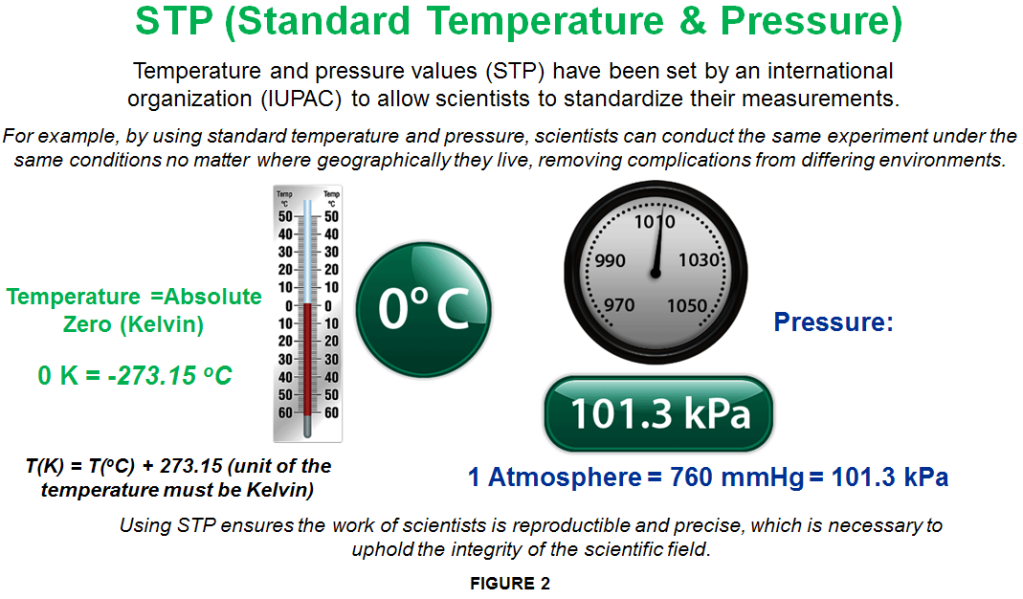

- The average kinetic energy of gas particles corresponds to the gas temperature on Kelvin scale. Absolute zero (0 K) is the temperature where molecular motion stops.

- In an ideal gas, particles have always a random and straight-line motion. They only change direction when they collide with their container or another particle.

THE IDEAL GAS LAW

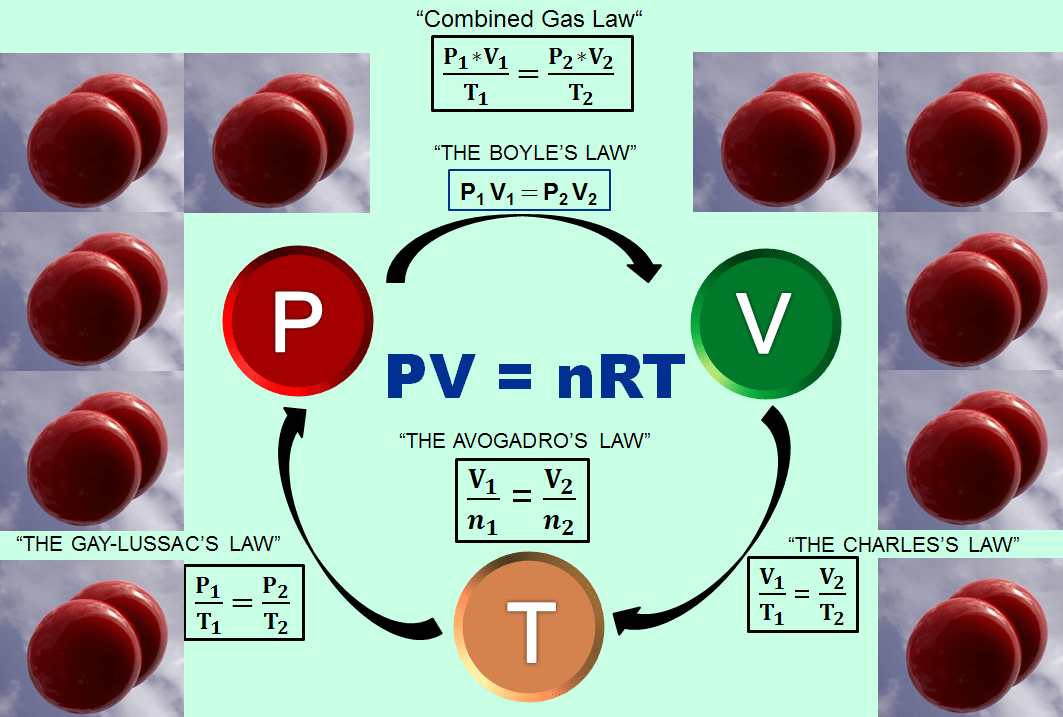

As mentioned earlier, the volume (V), pressure (P), temperature (T), and quantity (amount) of gas (n) all can affect one another. Since different gases act similarly, it is possible to write a single equation relating all of these properties which is defined as the Ideal Gas Law. In fact, this law combines the 4 ideal gas laws and the ideal gas constant (R ) into one neat and tidy formula!

PV = nRT

Where:

- P is pressure

- V is volume

- n is the number of gas molecules in moles

- R is the ideal gas constant

- T is temperature (which has to be in Kelvin)

This formula is often used when you want to determine the amount of gas that is present in a container. For example, you could find the mass of gas in a container by weighing the gas in the container, pumping out the gas and then reweighing the container. However, since gases have such low weight, the difference would be so small it would be hard to measure. Instead, all you need to know is the pressure – which can be obtained from a pressure gauge – the volume of the container, and the temperature of the gas. Then put these values into the formula and solve for n, from which the mass can be obtained. The laws come very close to describing the behavior of most gases, but there are very tiny mathematical deviations due to differences in actual particle size and tiny intermolecular forces in real gases. Nevertheless , using this law, you can easily find the value of any of the other variables — P, V, n or T — if you know the value of the other three.

This shows that the ideal gas law states that all gases contain the same number of gas molecules when they are under equal temperature, volume, and pressure. That’s why 1 mole of any gas fills a volume of 22.4 liters at STP (Standard Temperature & Pressure) (Note: This does not mean that the gases have equal masses!).

Although in reality no gas is an ‘ideal gas’, some gases do come very close. Therefore, the Ideal Gas Law allows us to roughly predict the behaviour of any gas.

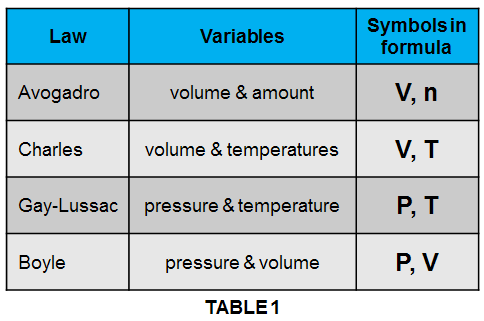

The table below shows how all the above gas laws are present in this ideal gas law.

THE KINETIC MOLECULAR THEORY.

The 4 gas laws I’ve mentioned earlier are the basics about gases. Yet, like any laws, these ideal gas laws are merely summaries of observations, such as the way pressure and volume are inversely proportional (Boyle’s law) or the way volume and temperature are directly proportional (Charles’s law). We observe these relationships to always be true, but again, just like any other law, it does not explain why. For that, we are going to need something more powerful, we need a theory. And the theory that explains this behavior of gases is called kinetic molecular theory. This theory consists of 5 postulates, and from them all of the ideal gas laws can be derived. Let’s go through each postulate and talk about what they mean.

POSTULATE 1 => GAS CONSIST OF PARTICLES IN CONSTANT MOTION

We make the assumption that a gas is made up of particles, whether they are individual atoms or small molecules, and that these particles are in constant motion. Throughout their motion, the gas particles travel in straight lines unless they collide with something, whether that is another gas particle or the walls of whatever container they are in, at which point they will bounce off and change directions. This vision of gas particles as moving around like billiard balls on a pool table seems pretty intuitive, but it is an important one, as it implies that tiny particles like atoms are subject to laws of motion just like macroscopic objects are, and that they won’t just stop in their tracks and change direction without cause.

POSTULATE 2 => GASES ARE MOSTLY EMPTY SPACE

We can assume, under most sets of conditions, that the gas is mostly empty space. This means that the fraction of the total volume that is occupied by the particles of gas themselves is so close to zero that we simply ignore it, regarding them as essentially dimensionless points. This is in stark contrast with solids and liquids, which are non-compressible, because all the particles are pretty much right up against one another, there is very little empty space between the particles.

POSTULATE 3 => GAS PARTICLES EXERT PRESSURE WHEN COLLIDING WITH THE CONTAINER

The phenomenon we refer to as pressure is actually the gas particles in the sample imparting some of their kinetic energy of motion onto the walls of the container every time they collide with it, just like a macroscopic object would transfer energy onto some surface during a collision. It may seem like atoms are so tiny that they can’t impart much force, and that’s true, but remember that in any sample of gas there are trillions and quadrillions of particles, so all together, it can add up to a lot. If there are a lot of particles moving very fast, there are many collisions, so the system has a lot of pressure. If there are very few particles moving very slowly, there are very few collisions, and thus the system has very low pressure.

POSTULATE 4 => GAS PARTICLES DON’T INTERACT WITH EACH OTHER

We ignore the possibility that gas particles could exert any kind of gravitational or electromagnetic influence on one another. Although they technically can interact slightly, due to dispersion interactions or even dipole-dipole interaction if the molecules are polar, we consider such interactions to be entirely negligible, so any collision will be purely elastic, or occurring with no loss of kinetic energy. They will simply bounce off of one another once again, like balls on a pool table.

POSTULATE 5 => AVERAGE MOLECULAR SPEED OF GAS PARTICLES (their kinetic energy) IS PROPORTIONAL TO TEMPERATURE

The average kinetic energy of the particles in the gas is proportional to the temperature of the gas in Kelvin.This means that if you increase the temperature, you increase the kinetic energy, which means the particles will be moving faster. This means that in this specific context, temperature is entirely indicative of average molecular velocity.

=================================

So those are the 5 postulates of kinetic molecular theory. These postulates are powerful in explaining the behavior of gases. To see how, let’s quickly review our understanding of some of the ideal gas laws.

For Boyle’s law, we can see that if we keep temperature constant, meaning the molecules move at the same speed, increasing the volume must decrease the pressure, because the particles have to move faster to reach the sides. And decreasing the volume must then increase the pressure. This is why pressure and volume are inversely proportional.

For Charles’s law, if we increase the temperature, in order to keep pressure constant, meaning the frequency of collision stays the same, the volume must expand, because if the particles move faster but also move farther, they will hit sides with the same frequency as before. This is why volume and temperature are directly proportional.

For Gay-Lussac’s law, we can see that increasing the temperature while keeping the volume constant, the pressure must increase as the particles are moving faster. This is why pressure and temperature are directly proportional.

Kinetic Molecular Theory has the power to explain all of the ideal gas laws. All of these laws, which are simply statements of observation, now make perfect sense in the context of kinetic molecular theory.

In additon to what has been said about the characteristics of Ideal Gas we can also add the statement that: ”An ideal gas, obeys the assumptions of the kinetic molecular theory.”

Leave a comment