Air-conditioning systems are essentially refrigerators for air. In your car, for instance, the air-conditioning system passes the cabin air over copper tubes containing refrigerant, thus cooling the air. Cool air can’t maintain a high concentration of water, which is why water droplets form on air conditioners (this is also why clouds form as air rises and becomes cooler). Hence a by-product of air conditioning is that it dehumidifies the air. In hot, humid countries air conditioning is often the only way to make traveling by car, bus or train tolerable. But it also consumes a huge amount of energy. In Singapore, for instance, cooling accounts for about 50% of the energy consumption in homes and offices. In the US, the entire transport sector, including trains, planes, ships, trucks and cars, accounts for 25% of the country’s energy use, while the heating and cooling of buildings through air conditioning accounts for nearly 40%.

And just as the back of your fridge gets hot as result of cooling the interior, so too does air conditioning a vehicle or building release that heat back into the environment, raising outside air temperatures. The overall effect of this isn’t huge except in dense cities, where the temperature rise due to air conditioning is appreciable. Scientists at Arizona State University have shown that, solely because of air conditioning average night-time temperatures have increased by more than 1°C in urban areas. That doesn’t sound like a lot, I admit, but, remember, even a 2°C increase in global average temperatures is likely to lead to severe climate change. Making air conditioning more energy-efficient is thus a global challenge.

To increase the efficiency of cooing systems, the heat has to conduct quickly through the metal pipes, which is why we use copper (Cu) for air-conditioning pipes. Copper may be expensive, but it’s a very good conductor of heat. But on a very hot day in a stuffy office with the outside temperatures approaching 40°C, even copper sometimes isn’t enough to keep the room cool. The way the liquid coolant flows through the tubes can tip the balance though.

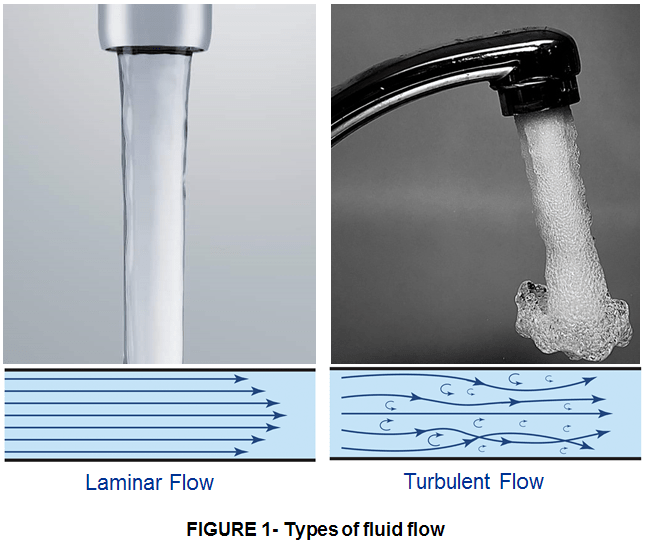

Uniform (Laminar) flow, like water coming out of a pipe, is predictable, but its speed is inconsistent within the stream. Generally the outer part of the flow, the part nearest the pipe – also called the boundary layer – is slower than the inner part. There isn’t much thermal interaction between these two layers, which decreases the speed at which the heat is conducted away. The cooling system is considerably more efficient if you can achieve what’s known as a turbulent flow. This is a chaotic state of flow, where the liquid tumbles and creates vortexes, mixing everything together quite thoroughly. Increasing the pressure is one way to get turbulence (turning the tap on all the way, so the water comes tumbling out of the pipe chaotically), but that uses up a lot of energy. It’s better if you can disrupt the boundary layer, which we accomplish by making helical grooves inside the copper pipe so that they break up the uniform flow by constantly mixing the liquid. This has become the preferred means of getting a turbulent flow, which allows the cooling liquid to extract heat more efficiently, radically increasing the efficiency of air conditioning without any extra energy expenditure. Genius, eh?

Einstein missed this idea. This system of creating a turbulent flow was invented in the 20th century, at a time when Einstein was already dead and the state of the air-conditioning sector hadn’t progressed beyond it. Grooved copper tubes are made through a process that’s pretty similar to squeezing toothpaste – just imagine that, instead of toothpaste, there’ s a bullet inside the tube, with a diameter that’s slightly greater than the nozzle so it doesn’t squirt out when you squeeze. Instead, the bullet gets pushed against the nozzle, and the tube flows around it, which stretches out the copper. But because there are helical grooves on the bullet, as you squeeze, the bullet spins and carves it grooves into the inside of the copper tube. Magic!

The only problem is that the bullet had to be made by bolting together several components made from a super-hard material called tungsten carbide, and inside the massive copper-squeezing machine the pressure often got so high that the bolts snapped off, the bullet fell apart, and the whole thing ended up in a big mess and cost millions of pounds to sort out. It was determined that we could bond the 2 halves of the tungsten carbide bullet together by turning the inside of the material into liquid, while keeping the rest of the material solid. It’s a kind of very precise welding. And like a lot of discoveries, once you know the trick, it’s easy to do.

The engineers who found this solution just had to compress the 2 parts together and put them into a high-temperature furnace. This caused liquid to form inside the material; it flowed between the two pieces and then joined them together. Once it all cooled down, you were left with single, seamless piece of tungsten carbide. But that didn’t mean the bullets would hold together through practical use. So they did a trial and good news was that it worked perfectly and they filed for a European patent, as “Method of liquid phase bonding”.

Miraculously, by late 1920’s the liquid that solved the problem was found. That was made by replacing hydrogen atoms in hydrocarbons with fluorine and chlorine, hence resulted a new family of molecules known as ChloroFluoroCarbons (CFC’s), which since then started to be used as cooling liquids for refrigerators and air-conditioning systems.

Finding ways to cool more efficiently is all good, yet there were larger problems looming. So much work had gone into making cooling systems work better, but no-one had thought about what would happen when the fridges and the air conditioners stopped working. They just went to rubbish dump, where the valuable metals were salvaged -the steel from the frame of the fridge, and the copper tubes.

But there was a problem with here. No one collected the ChloroFluoroCarbons (CFC’s); they evaporated quickly, as soon as the copper pipes were cut, cooling them one last time as the liquid evaporated into thin air. Ironically No one was worried about them. CFC’s were already being used as propellants in cans of hairspray and other disposable items: they were supposedly inert, so what harm could they do? It was just assumed that once they became a gas, they’d be dispersed by the wind. Which is exactly what happened. But over the course of decades they found their way into the stratosphere, where they started to get broken down by the ultraviolet light from the sun, into molecules that could do us a lot of harm.

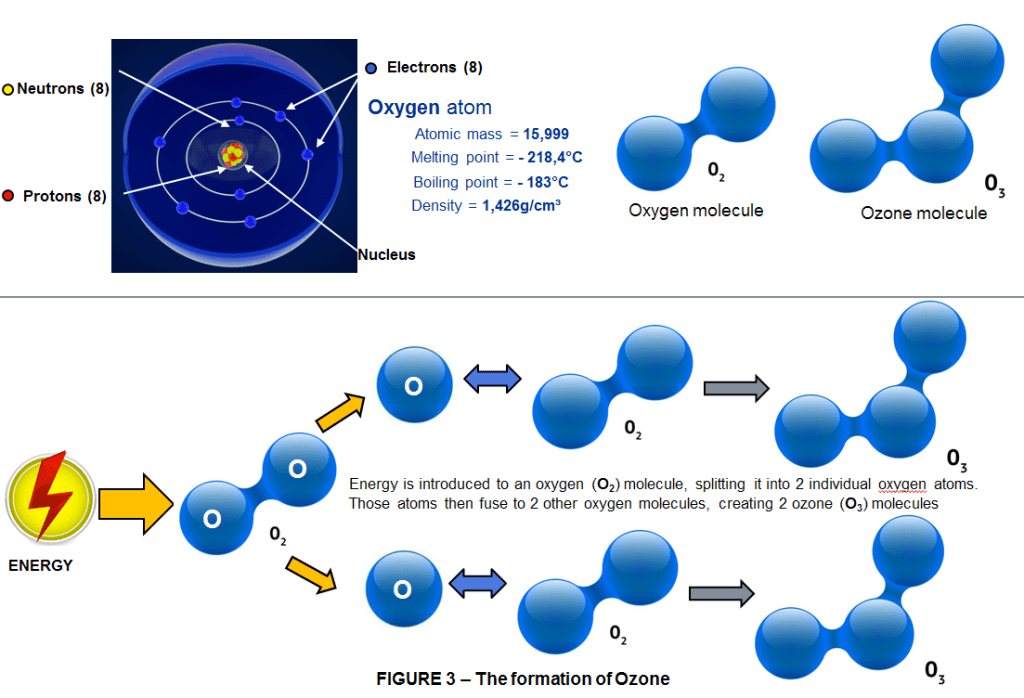

The sun emits light we can see and light we can’t see. Ultra-violet light is the latter. It’s the light that gives us a tan, and because it has so much energy, it can and does burn us: prolonged exposure can damage your DNA, and eventually causes cancer. This is why wearing sun cream is essential; the job of this liquid is to absorb ultraviolet light before it hits your skin. But there’s another barrier between you and the ultraviolet light that’s a lot more effective – the ozone layer. Ozone is like a sun cream for the planet, and like sun cream you can’t really see it once it’s been applied.

In fact, when a plane is flying through the ozone layer, but looking out of the window, you’d have no idea. Ozone is related to oxygen. The oxygen we breathe is a molecule made up of 2 oxygen atoms bonded together (O2); Ozone is a molecule made up of 3 oxygen atoms bonded together (O3). It’s not very stable, and, being highly reactive, it doesn’t stick around for long. Ozone also has a smell, which you can sometimes detect during the production of sparks – some of the O2 in the air is transformed into O3 as it encounters the spark’s high energy, and the resulting reaction produces a strange pungent smell. But while there’s not a lot of ozone in the air we breathe down on terra firma, up in the stratosphere there’s enough ozone to form a protective layer that absorbs ultraviolet light from the sun.

But when CFC molecules find their way into the ozone layer, they break down after interacting with the high-energy rays of light emitted from the sun. This creates highly reactive molecule called free radicals; these then react with the ozone an decrease its concentration, thus depleting our ozone layer. Chlorofluorocarbons are also very potent greenhouse gases that contribute to the increased greenhouse gas effect. The increased greenhouse gas effect results in an increase of the average temperature on earth, which for example leads to climate change and rising of the sea level. Some chlorofluorocarbons may cause long-term damage to aquatic organisms. Health effects vary somewhat between different chlorofluorocarbons. Some chlorofluorocarbons may be harmful by skin contact or even cause severe eye irritation.

By the 1980s, atmospheric scientists had begun to realize that the effect of CFC’s on our ozone layer was significant and had huge consequences. In 1985, scientists from the British Antarctic Survey reported that there was a hole in the ozone layer, spanning 20 million km2, above Antarctica and not long afterwards it was determined that, across the globe, the thickness of the ozone layer was degrading. CFC’s are, by and large, to blame for this, and so an international ban, called the Montreal Protocol, was put in place and took effect in 1989. CFC’s in refrigeration were banned, was their use in dry cleaning, where they were used instead of water to clean clothes. But despite the swift response of the global community, there are still CFC’s in circulation, and other holes have opened up in the ozone layer. In 2006, a hole of 2.5 million km2 big was found over Tibet, and in 2011 there was a record loss of ozone over the Arctic, which suggests we won’t be able to recover from all this damage until the end of the 21st century. The world has managed to avoid catastrophic loss of the ozone layer by banning CFC liquids and replacing them with fluids less damaging to the environment – these days the refrigerant in your fridge is likely to be (iso)butane or other Natural refrigerants (such as ammonia, carbon dioxide, propane or even water).

IsoButane it’s a highly flammable liquid, and if it leaks from the back of your fridge it could be hazardous, but it’s still safer than the liquids used in Einstein’s day, and it’s a much better bet for the planet. Our protective sunscreen layer of ozone is too precious to destroy with CFC’s. So even if it’s not really suitable for any air-conditioning systems, for example it’s actually quite risky for air-co used in aircrafts, the risk of using butane may be small enough for domestic refrigerators.

Leave a comment