From the first objects ever created by man we always needed to put parts in a functional assembly. Nowadays, our technology is already advanced and the objects we create are almost entirely made of different parts put together in a stiff and functional product. There are multiple ways we can do this.In case of plastic parts a frequent way to assembly the component parts of a product is to use Snap-Fits. For metallic parts, depending of how we want to use the final product, in case it must have easily replaceable components we can use bolt and nuts, or in case we want to build something solid and permanent we can also weld 2 or more metallic parts together. We can do that wit plastics as well, by laserwelding, and so on. There are multiple ways to assembly the component parts in one final assembly.

Yet the oldest way ever used by humans to make assemblies of at least 2 parts is by Gluing. Therefore using adhesive materials.

In the course of time since their first use from the Middle Pleistocene era (circa 200.000 years ago) and during their development, adhesives have gained a stable position in an increasing number of production processes. There is hardly any product in our surroundings today that does not contain at least one adhesive—be it the label on a beverage bottle, protective coatings on automobiles, or profiles on window frames or in more advance versions on aeroplanes and other flying objects.

GLUE = is the most frequent material we use for everything we want to put fast and easy into an assembly. Hence glue, which is nothing else but initially a sticky liquid, an adhesive substance used for sticking objects made from different materials together. However GLUE used to build strong assemblies is a very specific and special material.

Many liquids are sticky – that is, they will stick to you if you put your finger in them. Oil sticks to us, water sticks to us, soup sticks to us, honey sticks to us. Thankfully they stick to other things better than us, which is why towels work.

For instance when you have a shower, water trickles down your body, sticking to your curves of your chest, belly and bum in defiance of gravity. This stickness is due to the low surface tension between the water and your skin. When the water comes in contact with the fibres of a towel, they act as little tiny wicks – just as candle wicks suck up liquid wax – so the micro-wicks of the towel suck the water off your body. Hence your skin gets dry, and the towel gets wet.

The stickness of liquids, then, is not a property intrinsic to any particular liquid, but is determined by how they interact with different materials. However just because something is sticky doesn’t mean it can be used to glue for example an aircraft together. Wet your finger and dab it on a speck of dust and it will stick to you, and remain sticking to you until the water evaporates. That water loses its stickness when it evaporates is why, although it is sticky, it is not a glue.

Glues starts off as liquids and then, generally speaking, transform into a solid, creating a permanent bond. This is a material process humans have been playing with for a very long time. Our prehistoric ancestors made pigments like powdered charcoal or naturally occurring coloured rocks such as red ochre, and used them to draw pictures on the walls of caves. To get them stick to the walls, they mixed the pigments with sticky things like fats, wax and egg, and so invented paints.

Paints are essentially coloured glues, and these earliest ones were permanent enough to last for thousands of years. Some of the oldest cave paintings still in existence are in the Lascaux caves in France, estimated to be about 20.000 years old. Tribal cultures have long used these coloured sticky substances as face paints, a central part of both sacred rituals and warfare. The tradition continues today with the modern cosmetics industry.

Lipstick, for instance, is made up of pigments mixed with oils and fats that allow the colour to stick to your lips – hence the name. Getting the glue to stick to your lips for hours, but still be easy enough to remove at the end of the day, has always been an issue; ditto eyeliner and any other kind of make-up. The problem illustrates one of the main themes in glue design – namely, that unsticking is often as important as sticking. But more on that later – mastering sticking is hard enough for now. If you want to stick something together that needs mechanical strength, like the components of an axe, a boat or, indeed, an aeroplane, then you need something stronger than paint or lipstick.

In the summer of 1991, 2 German tourists discovered the skeleton of a dead man while walking in the Italian Alps. The mummified man turned out to be 5.000 years old, and was later nicknamed Ötzi. His remains were extremely well-preserved because they´d been encased in ice since his death, as were his clothes and tools: he wore a cloack made of woven grass, a coat, a belt, leggings, a loincloth and shoes, all made of leather. All of his tools were ingeniously designed, but with respect to glue, it´s Ötzi´s axe that´s most interesting.

The axe is made of yew wood, with a copper blade, bound together with leather straps stuck on with a birch resin. This gummy substance is produced by heating up birch bark in a pot, yielding a brownish-black goo that was widely used as an adhesive in the late Paleolithic and Mesolithic eras. It works for heavy tools like an axe because when it solidifies, it forms a tough solid.

Our ancestors used it to glue arrowheads and flights, to make flint knives, to repair their pottery, and to make boats. The liquid is mostly made from a family of molecules called phenols. Their chemical name may be unfamiliar, but I´m sure you would recognize the smell: the major phenol in birch bark glue is 2-methoxy-4-methylphenol, which smells of smoky creosote and which is one of the constituents of birch bark glue. It is the hexagon of carbon and hydrogen atoms joined to an- OH hydroxyl group that is the hallmark of a phenol.

Phenol aldehyde smells of vanilla. Ethyl phenol smells of smoky bacon; indeed, whenever you smoke fish or meat, it´s the phenols that give them that distinctive flavor. When you heat up the birch bark, you extract the phenols. The thick resin that´s produced is basically a mixture of a solvent called turpentine and phenols. The turpentine is the base of the liquid, but over the course of a few weeks the turpentine evaporates. This leaves just the phenol mixture, which turns from a liquid into a hard tar, a tar sticky enough to bond wood to leather and other materials.

As it turns out, trees are excellent purveyors of sticky things. Pine trees exude nodules of resin that also make good glues. An adhesive popular for a thousands years, gum arabic, comes from the acacia gum tree. The resin of Boswellia tree is a particularly nice-smelling glue called frankincense.

Myrrh, another aromatic resin, comes from a thorny tree called Commiphora. Resins were often used in medicines as well as in perfumes, perhaps because their active chemical components, like phenols, had potent antibacterials properties. Frankincense and myrrh were so highly valued in antiquity that they were given as presents to queens, kings and emperors, which is why their presence in the Christian nativity story is so significant. The stickiness of the tree resins is no accident. They evolved to be sticky so they could trap insects, and therefore provide a valuable form of defence for the trees.

The gemstone amber is actually fossilized tree resin, and often there are insects and bits of debris trapped inside it, perfectly preserved. Without tree resins, it would have been very hard for our earliest ancestors to make tools and equipment, and so for our civilization to get off the ground.

Nevertheless, you wouldn’t want to glue an aeroplane together with them – they would certainly crack during flight. Phenol molecules don´t bond very strongly to other substances – the molecule itself is too self-contained, too happy sticking to itself. But once you´re in the tree, you don´t need to look very far for stronger glues.

Consider birds: their wings are not bolted or screwed together. Their muscles and ligaments and skin are bonded via families of molecules called proteins. Our bodies are bonded together with them too. One of the most important of these proteins is called collagen.

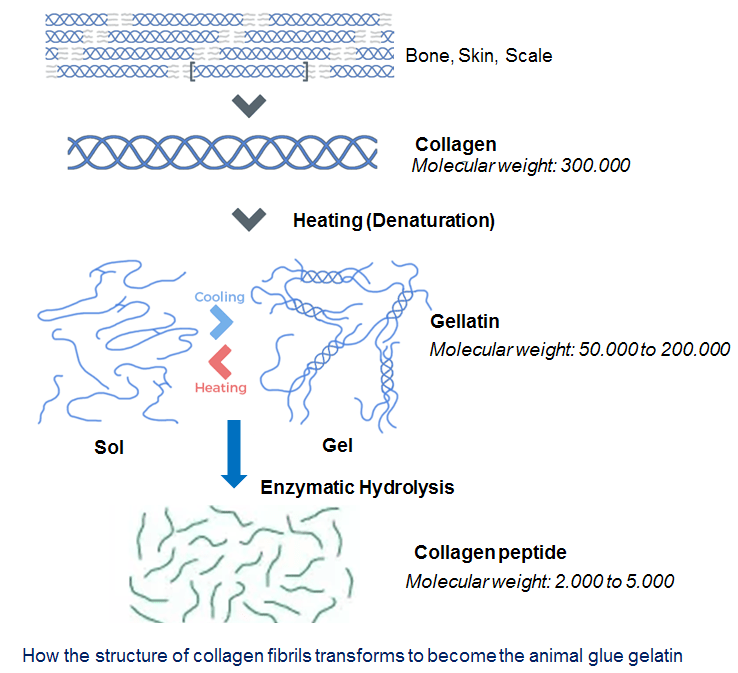

It is common to all animals and relatively easy to extract. Early humans used skins of fish and hides of wild game – they separated the fat and then boiled the skin in water. This extracts the collagen from the animals and creates a thick, clear liquid that turns into a solid, stiff material when it cools: gelatin.

The collagen proteins in gelatin are long molecules made from a carbon and nitrogen backbone. In animals, collagen molecules, stick together to create strong fibrils that make up your tendons, skin, muscles and cartilage. But once they’ve reacted with hot water in the glue-making processes, the collagen molecules separate. They now have chemical bonds to spare that they want to satisfy. In other words, they want to stick to something else – they’ve become the animal glue gelatin.

It was animal glues that replaced wood resins as the mainstay of early human technologies. The Egyptians, for instance, used animal glue to make furniture and decorative inlays. In fact, it appears that the Egyptians were the first people to use glue to get around one of the main mechanical problems of wood – that is has a grain.

The density and arrangement of the cellulose fibres in wood give it its grain, which is determined not just by the biology of trees but also their growth environment. Thus the grain varies from species to species and from tree to tree. The upshot is that wood is strong across the grain, but has a tendency to crack along it. This is useful if you are splitting logs for a fire, but if you are building a house, a chair, a violin, an aeroplane or pretty much anything out of wood, it presents a design problem. The thinner the piece of wood, the more cracking becomes an issue.

Counterintuitively, the solution to this problem is to cut the wood into even thinner pieces called veneer. The Egyptians were the first to make veneer. They stuck pieces of it on top of each other, so that the grain of each layer was perpendicular to the one above. This allowed them to construct an artificial piece of wood that didn’t have a weak direction: we now call this plywood. They used animal glues to stick the plywood together and that worked reasonably well. But as you´ll have seen if you’ve ever cooked with gelatin, animal glue dissolves in hot water. Unless kept absolutely dry, furniture made from animal glues falls apart. This seems like a huge defect, but Egypt is and was a very dry place, and so they managed.

Leave a comment