3D Printing is a relatively new technology which has gained a lot of attention lately. More and more application using this new tech-development have been already successfully implemented in various industries. Now it is going to be used on building roads too.

A new research has been quite recently done by a group of scientists at the Institute of Making (a multidisciplinary research club based at University College London – U.K.), where they are working on technologies that can help repair asphalt efficiently once the cracks have already got bigger: they´ve started 3D printing tar.

But will it work? Advanced Paving Technologies (APT) as it is called, proposes what they say is a new method of paving using 3D technologies. But wait, we already have machines that pave roads very well, what is the problem being solved here?

3D printing technology has previously been used to repair small damage in concrete road surfaces. But more recently has been demonstrated that it is also possible to 3D print asphalt into a crack to restore the road surface.

APT claims the issue is in the method of paving, which assumes a relatively flat surface, upon which fresh asphalt is applied. Normally, streets requiring repair are in fact nowhere near flat, as they’re full of potholes and other damage. They have an irregular surface. The standard practice today is to scrape off sufficient irregular material to produce a flat surface to apply the asphalt. APT says this 2-step approach is time consuming and expensive. That’s probably true, but how do they solve the problem?

They propose to pave directly on top of the potholed surface, thus eliminating the scraping stage. Here’s how it works:

– at the front end of the paver, a 3D scanner examines the surface to determine its shape. Then, the magic occurs: a variable screed automatically adjusts the paving depth to match the detected potholes, ensuring a perfectly flat roadway surface. Sounds good, but will this actually work? Hmmm… scientists dealing with this challenge are very suspicious.

First, repeated applications of this process will just make the roadway thicker, eventually flowing over the curbs! It’s very likely you’d have to scrape material down anyway eventually, perhaps even after only one or two 3D asphalt applications.

The second problem they see is more devious: the potholes are formed by weakened material on the surface, typically by pounding, but also erosion by water and ice – and mostly by ice freezing and expanding in cracks. As a result, you’d most likely find the areas immediately surrounding potholes to be quite weak and ready to break up. You cannot build a road on top of that weak material; it would quickly deteriorate. You’d also have to remove any loose material before 3D asphalting as well. So then how to design, build and test an asphalt 3D printer?

The main difficulty encountered is that asphalt behaves as a non-Newtonian liquid when moving through the extruder. By definition a non-Newtonian liquid is a fluid that does not follow Newton´s law of viscosity, i.e., constant viscosity independent of stress.

In non-Newtonian fluids, viscosity can change when under force to either more liquid or more solid. Ketchup, for example, becomes runnier when shaken and is thus a non-Newtonian fluid. Most commonly, the viscosity (the gradual deformation by shear or tensile stresses) of non-Newtonian fluids is dependent on shear rate or shear rate history. Thus, the rheology and pressure in relation to set temperature and other operational parameters showed highly non-linear behaviour and made control of the extrusion process difficult. This difficulty was overcome through an innovative extruder design enabling 3D printing of asphalt at a variety of temperatures and process conditions.

However by using the 3D printing the scientists demonstrate the ability to extrude asphalt into complex geometries, and to repair cracks. The mechanical properties of 3D printed asphalt are compared with cast asphalt over a range of process conditions. The 3D printed asphalt has different properties from cast, being significantly more ductile under a defined range of process conditions. In particular, the enhanced mechanical properties are a function of process temperature and scientists believe this is due to microstructural changes in the asphalt resulting in crack-bridging fibers that increase toughness. The advantages and opportunities of using 3D printed asphalt to repair cracks and potholes in roads are therefore evaluated.

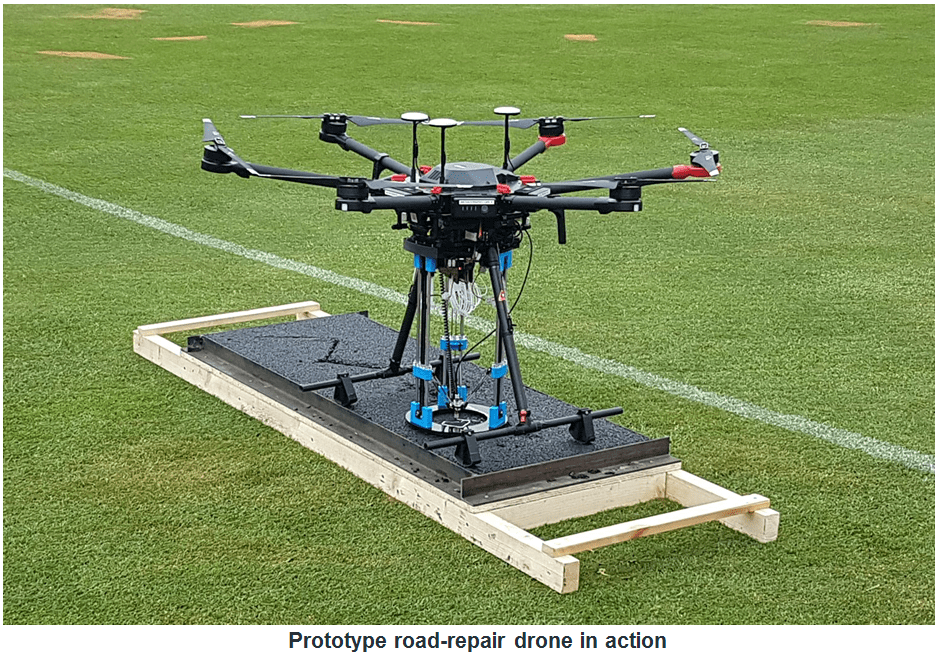

So in this case we must describe a 3D printing technology that could be attached to an autonomous vehicle or drone, and used to repair small cracks before they turn into potholes is. 3D printing is a method by which objects can be fabricated layer by layer from a CAD model of the object. By scanning a road surface the negative shape of the crack can be obtained and processed into a 3D model. This information can then be processed and passed to a 3D printer, which can then print exactly the correct amount of material to conform to the crack shape and volume, thus repairing the crack.

Asphalt is a substance made principally of long-chain hydrocarbon molecules in a colloidal structure of asphaltenes and maltenes with complex rheological properties. Above a threshold temperature, typically between the range of 30–70 °C, it behaves as a Newtonian fluid. Below this threshold, it undergoes shear-thinning. In the face of this complexity, the scientists chose not to try to model the regime of rheology under different shear stresses as the asphalt pellets traveled through the extruder, but instead they aimed to find the optimum processing variables by carrying out a systematic empirical investigation of the extrusion process through a number of design iterations (such as design parameters of the extrusion nozzle, heating chamber, extrusion screw and process parameters such as temperature, power limit and torque limit). The results were remarkably good.

With these experiments the scientists have successfully managed to design, build and test an asphalt 3D printer capable of printing small objects and repairing cracks in asphalt. The main difficulty they encountered is that asphalt behaves as a relatively low melting point non-Newtonian liquid when the material is moving through the extruder as it is heated up, and then in between the extruder tip and deposition surface, as it cools down.

Although polymers used in filament-fed 3D printers are generally non-Newtonian too, their simpler extruder system makes flow control much easier. Flow through the auger screw extruder used in asphalt case created a more complicated regime of rheology and pressure in relation to set temperature and other operational parameters which showed highly non-linear behaviour and made control of the extrusion process difficult. The functional constraints of some of the process variables affected the ability to print asphalt, for instance, the rotation speed of the auger screw is linked to the print speed (the extrusion multiplier is programmed to double the rotation speed if the print speed is doubled in order to deposit material at the same rate).

The print speed was also limited by the materials properties of the auger screw (they used the high temperature SLA resin), since the low fracture strength of this resin limited the torque they could apply. The aperture affects the resolution of the printer, but again, low fracture strength of SLA resin limited their ability to reduce aperture size since it led to high pressures and resulted in mechanical failure. It is hoped that future designs with metal parts will allow us to explore a greater range of extrusion rates and print resolutions.

The impact of 3D printing on mechanical properties is interesting because it allows us to print a more ductile asphalt. There is a significant increase (up to 900%) in elongation to fracture for the printed samples. A possible explanation of this increased ductility lies with the appearance of a crack bridging component in the samples.

With the correct parameters, is possible to modulate the asphalt properties through changing print temperature fairly rapidly over a small 10–15 °C range. Furthermore, the feed and pellet system make it relatively straightforward to add other materials such as small microaggregates or nanomaterials (initial test prints with 10% 10nm diameter titanium dioxide nanoparticles have been successful), and then vary the composition of the feedstock during printing to create more complex, functionally graded infrastructure materials with a wider range of properties.

It is believed that these improved and tunable material properties of 3D printed asphalt, combined with the flexibility and efficiency of the printing platform, offers a compelling new approach not just to the maintenance of road infrastructure, but by attaching it to a drone, opens up a new way to repair hard to access structures such as the flat roofs of buildings and other complex structures. The advantage of this is not only in being able to cut costs – other repair methods often requiring the erection of scaffolding and the closure or shutting down of infrastructure to gain access – but also the repair can initiated earlier before large scale deterioration has occurred. The development of such repair drones would have implications both for the way in which city infrastructure is repaired but also for the economic model that underpins it.

At the moment, much of city infrastructure is built to fail and then be replaced, with the capital costs of construction dominating the design parameters. Infrastructure designed to be continually monitored and repaired by fleet of drones promises to be a different model which could have economic benefits to society.

For instance, such an approach has the potential to be used for roads. If road degradation is continually monitored then small cracks can be repaired before they turn into potholes. By intervening at this early stage and repairing the crack autonomously using 3D printing the road surface might be preserved for longer. Such approaches have been explored for concrete road surfaces for spall damage repair. It was already demonstrated that the 3D printing of asphalt using a drone is possible. The next stage of developing this technology involves understanding the effect of environmental variables such as road temperature, air temperature, the local chemistry, interface with aggregate, as well as more comprehensive testing such as cyclic loading of repaired crack roads.

The materials science of repair is not the only consideration in the application of this technology. Identification and detection of crack morphology, especially in the case of complex-shaped cracks will be an important challenge. Automated computer vision systems are currently being explored to address this issue. The use of gantry systems versus the employment of 6-axis robotic systems is another design issue that is pertinent in the area of automated construction and repair. Although 6-axis systems have more flexibility; for the repair of sub-cm small cracks in a horizontal road surface, a simple gantry system, such as the one I’ve talked about in this article, may well prove effective enough.

Leave a comment