The huge success of carbon fiber composite in the second half of the 20th century, inspired engineers to imagine its use on the grandest possible scale, hence they started to ask: is this material strong enough to achieve a longstanding dream, that of building an elevator into space?

A Space Elevator promises to replace the roar of rocket launches with the hum of electric motors, the flash of ignition with the glint of sunlight on a ribbon stretching from Earth’s surface into the black space. And like all grand engineering projects – whether the Roman aqueduct, the transcontinental railroad or the internet – it’s not just about getting from point A to B. It’s about changing what A and B even mean. Because a Space Elevator isn’t just a new way to get to space – it’s a foundation for building in space. Once you’re hauling hundreds or thousands of tones as cargo to geostationary orbit each day, suddenly habitats, solar farms, shipyards and even Moon-bound transports become not only practical but commonplace. If a space elevator could be constructed, it would democratize space travel at a stroke, allowing people and cargo to be transported into space with ease and with an almost negligible energy cost. But what does a Space Elevator even mean?

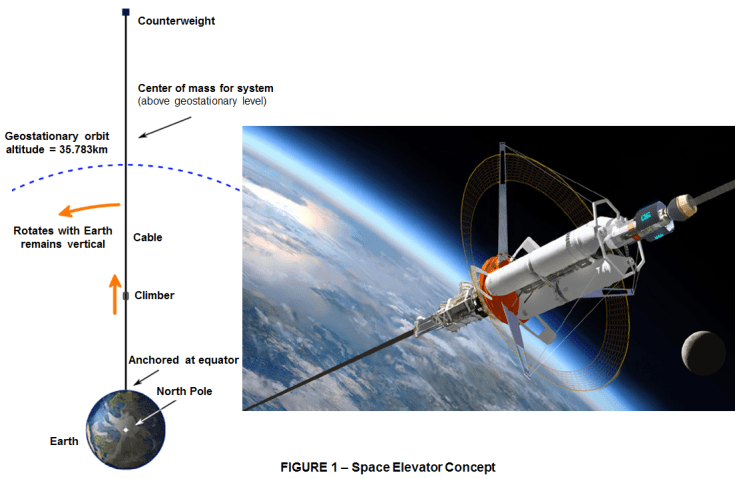

A Space Elevator would be a structure anchored to the Earth through a cable all the way up to the geostationary satellite. In a more precise description a geostationary orbit means an altitude of 35.786 km above the Earth’s equator. At that altitude an object orbits the Earth at the same speed the planet rotates, appearing stationary in the sky.

The concept involves a tether stretched from the Earth’s surface all the way up to a counterweight in space held taut by centrifugal force. Along this tether, mechanical climbers would ascend and descend carrying cargo, equipment, and eventually even people without using rocket fuel. The appeal is obvious. Rockets are expensive, dangerous, and incredibly inefficient. Most of their energy is spent just fighting gravity and air resistance to reach orbit. A space elevator would eliminate the rockets to lift payloads into space. It would reduce launch cost by a factor or 100 or more. Imagine launching satellites for few hundred dollars per kg instead of tens of thousands. That alone could revolutionize space access.

But here is the catch, building something that tall, far taller than any skyscraper, mountain or even orbiting spacecraft is beyond anything we’ve ever done. The engineering challenges are staggering. The biggest problem: MATERIALS.

POTENTIAL MATERIALS FOR SPACE ELEVATOR CABLE

For decades, the idea of a space elevator was pure science fiction, a vertical railroad to the stars- grand, elegant and utterly impractical. But science fiction has a habit of becoming science fact, and the last few decades have seen a quiet revolution in materials science that may turn this dream into a pillar of our civilization. Of course for that to happen, we need 2 things: the right material and the right math. The rope must be stronger than steel, lighter than aluminum, and longer than anything we’ve ever built. And it has to make economic sense too. Even a bridge to the stars still needs someone to pay the toll.

To work, the space elevator’s tether must be both incredibly strong and extremely light. All studies so far indicate that the idea is mechanically feasible, but requires the cable to be made from a material with an extraordinarily high strength-to-weight ratio. The reason why weight comes into it, as with any cable structure, is that it must first be able to hold its own weight without snapping. At 36.000 km long, you would need a material so strong that a single thread of it could be used to lift an elephant.

No known conventional material, steel, titanium, Kevlar or anything like that, can support its own weight over such a lengths, let alone carry climbers and cargo. In practice even the best carbon fiber thread could only lift a cat. But this is because it is full of defects. Theoretical calculations make clear that if a completely pure carbon fiber could be engineered then its strength would be much higher, exceeding the strength of diamond. The search is already on to find a way to make such a material.

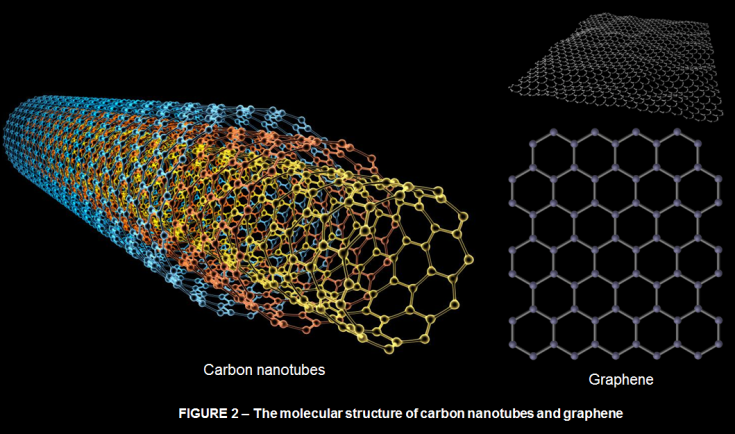

Things really became very interesting in this direction since 1991 when the Japanese scientist Sumio Iijima while doing experiments in his lab at NEC, managed to synthesize Carbon Nanotubes. Likewise as it followed in 2004 when prof. Andre Geim and his team at the University of Manchester, discovered Graphene. Both Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene being newly discovered carbon allotropes which have unique properties unlike any other material known before them.

However it took a while to experiment more and just until 2020-the idea to use such a material to manufacture a cable for Space Elevatror was mostly theory. Today it’s prototypes, production methods and megastructure math. Not really in the sense that we are now ready to build space elevator for real, of course we are not there yet, but significant progress has been made. Technically speaking we already have the material, yet difficulty lies: Manufacturing carbon nanotubes.

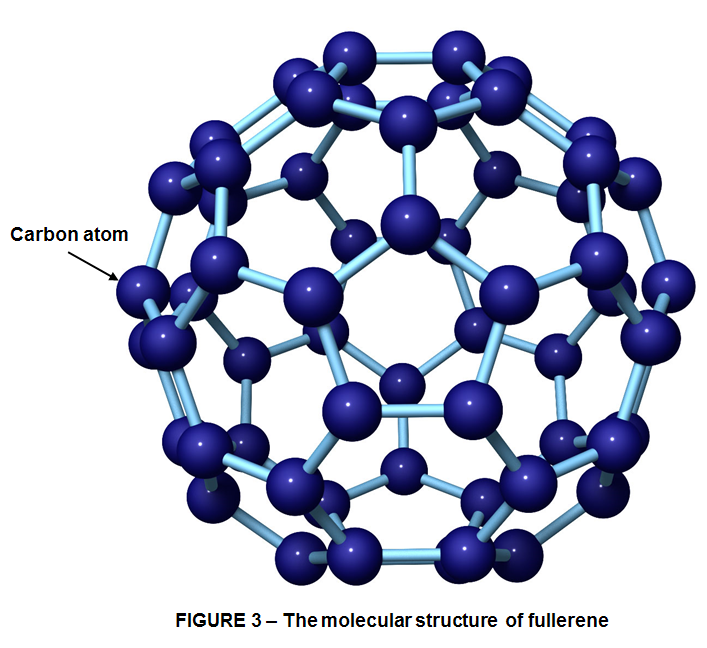

Single-wall carbon nanotubes are a new form of carbon made by rolling up a single graphite sheet to a narrow but long tube closed at both sides by fullerene-like end caps. (a fullerene is another super interesting carbon allotrope which is a molecule made entirely of carbon atoms arranged in a hollow sphere, ellipsoid, or tube shape). However their attraction lies not only in the beauty of their molecular structures but through intentional alteration of their physical and chemical properties fullerenes exhibit an extremely wide range of interesting and potentially useful properties, too.

Carbon nanotubes are like miniature carbon fibers except that they have no weak van der Waals bonding. They were found to have the highest strength-to-weight ratio of any material on the planet, which meant that potentially they might be strong enough to build a space elevator.

Problem solved? Well, not quite. Carbon nanotubes are, at most, a few hundred nanometres in length, but they would need to be meters in length to be of use. Carbon nanotubes strength relies on creating a continuous perfect lattice of carbon atoms in a long tube; so in theory a ribbon of carbon nanotubes could support a space elevator. But in practice we can’t yet manufacture nano tubes in the required length or quality.

Currently there are hundreds of nanotechnology research teams around the world working to solve this problem. And that’s changing. In recent years, material science, has made rapid progress. Scientists can now grow longer, pure carbon nanotubes in labs. Techniques are improving. Some researchers believe we may be able to produce elevator grade materials within decades. It won’t be easy. We’re talking about a tether tens of thousands of km long, made of ropes thinner than a pencil, yet stronger than anything ever built.

The most famous part of a space elevator is the tether – an impossibly long cable stretching from the equator up past geostationary orbit. But what’s less often appreciated is just how absurdly strong that cable needs to be. Not strong like steel, not even strong like Kevlar or carbon fiber. These could work much better on the Moon, Mars and other places of low gravity, but we need more to leave Earth. Every material has a breaking length – the length at which a material can hold up its own weight.

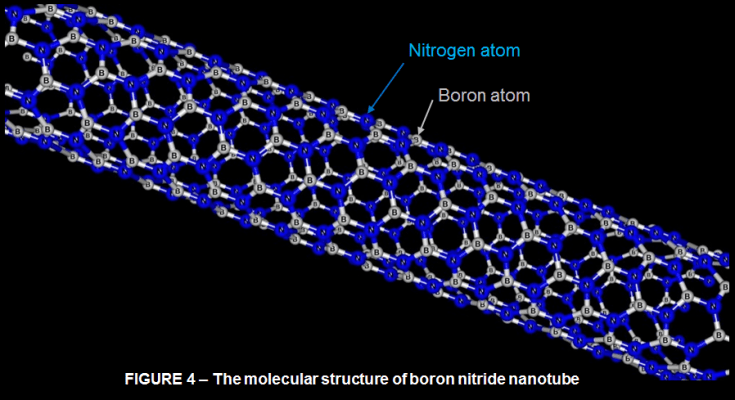

And our tether will be stretching 36.000 km. Low gravity as we get away from Earth help us quite a lot but we still need something very impressive.This is where materials like Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes, Boron Nitride Nanotubes, and Graphene Superlaminate come in.

Single crystal Graphene is just that, as it has a breaking length of 6.366 km. This incredibly tight atomic spacing means the structure has almost no room for deformation. Defects struggle to spread and even small areas can carry immense loads. The result is a material with theoretical tensile strengths upwards of 130 GigaPascals – around a 100 times stronger than steel by weight. It’s not just a strong material – it’s a textbook example of what strength can look like when built atom by atom. Now that’s the theory.

In practice we aren’t making flawless monocrystalline hammocks yet. But we are making polycrystalline graphene- patchwork versions with slightly lower tensile strengths, typically in the 60 -100 GPa range. Still far stronger, than any conventional material and with rapidly improving manufacturing methods like Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) and roll-to roll synthesis, we’re already producing ribbons and sheets that are meters long and millimeters wide, instead of just microns across. They’re still a thing as a surround wrap but they’re growing.

What matters more that peak performance is breaking length – the point where gravity would snap a dangling cable or ribbon under its own weight. Steel has a breaking length of only 25km. Kevlar might get you to +200. Again graphene can hit 6366 km maximum – which actually is more than good enough for a space elevator, if you tapper the tether smartly, adding width and layers toward the top where tension is highest. Gravity drops as we move away from Earth, and that – combined with a tapered design – lets us extend a tether well beyond what its raw breaking length would otherwise allow.

And yes, even imperfect graphene may be good enough. Because this isn’t just a matter of raw strength, but of density and scalability. Multi-layers single-crystal graphene is 2299 grams/cm3 – about the same as plastic. It’ strength-to-weight ratio is so extreme that we could build tethers with redundancy, building multiple sheets or strands to improve durability without losing viability. But it’s not just about graphene. Carbon Nanotubes – rolled-up cylinders of graphene – bring different strengths to the table.They have superior elongation properties, and can form fibers with less defect propagation which may make them easier to spin into cables.

And Boron Nitride Nanotubes, while not quite as strong are electrically insulation and thermally stable – making them good candidates for protective sheathing or hybrid designs. Like graphene, boron nitride its 2D form benefits from tightly bonded, hexagonal lattices though with different atoms. These give it strength, flexibility and resilience in harsh conditions, from high temperatures to ionizing radiation. They also have a higher coefficient of friction, which makes them easier to grip than graphene – a useful trait when building something you want climbers to stick to, not slip off and so they can push and pull themselves on it.

The real trick lies in its dimensionality. As a 2-dimensional material, graphene has no loose ends – forces are distributed evenly across its sheet like structure. That’s what makes it not just strong but remarkably efficient at staying strong under tension. Needless to say, that level of atomic perfection is hard to manufacture at all, let alone in bulk. And that’s why we’re not already weaving tethers to the stars; because building a 36.000km ribbon isn’t just a materials challenge – it’s a manufacturing revolution. Even so , we’re making real progress. Graphene-enhanced materials are in the market: Concrete roads with better durability, longer-lasting batteries and flexible electronics, we already have all these.

Besides, Carbon (C) is one of the most abundant elements in the universe. Unlike the expensive rare-earth metals in your smartphone or the cryogenic ices of Europa (the satellite of Jupiter), this is an easily accessed, cheap and abundant homegrown material. You don’t need to fly to Titan to get it. You just need a lot of carbon – of which have an abundance all around us – and a way to organize it very very well. So we’ve not just waiting for some magical unobtainium. We already have the ingredients. Now we’re learning how to cook.

Leave a comment