Helium-3 (3He) isotope is extremely rare on Earth. Most of our supply comes indirectly from tritium (3H)decay in nuclear stockpiles, producing only modest quantities. Likewise a minor amount of 4He isotope is collected as a by-product of big companies tapping natural gas. For most people this is not a topic of much interest, so why is this such a big concern?. This will soon become a most wanted commodity. Let’s explore what’s going on with it.

WHY HELIUM MATTERS?

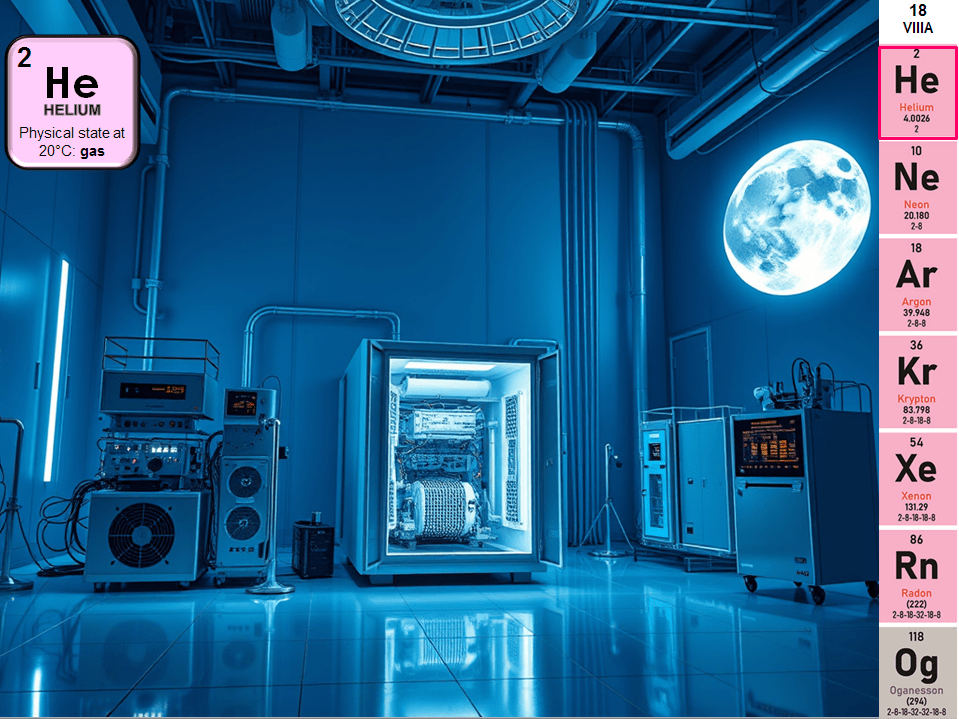

The 3He isotope is used in applications such as weapons detection in national security, cooling systems necessary for quantum computing, medical imaging (MRI), and developing clean fusion energy. Figures cited in industry discussions put annual yields from these sources at a few thousand to tens of thousands of liters, far short of what a fully scaled quantum industry might demand.

In quantum computing, Helium-3 is a workhorse behind the scenes. State-of-the-art dilution refrigerators exploit mixtures of 3He and 4He to cool qubits down to millikelvin temperatures (mK°) where fragile quantum states can persist. Just to underscore how essential extreme cold is to reducing errors and making quantum machines useful, it’s legit to say that such cold is the equivalent of being 200 times colder inside a Blue Origin fridge than outer space. If quantum data centers scale up as companies and nations expect, demand for 3He could balloon well beyond what Earth can supply.

Beyond quantum, the 3He isotope’s appeal is broader still. Helium-3 is a superb neutron absorber, useful for radiation detectors, and when hyperpolarized, it improves some medical MRI scans. The most intoxicating possibility, however, is fusion. It is thought that this isotope could provide safer nuclear energy in a fusion reactor, since it is not radioactive and would not produce dangerous waste products. Fusion reactions that use 3He produce charged particles rather than neutrons, meaning far less long-term radioactivity in reactor materials. Fusion reactor technology itself has been stuck with various obstacles for decades, but some argue that a significant supply of 3He could be the needed game-changer.

An even larger potential game-changer could be space-based solar energy. It would be not just signals from space, but wireless power available 24/7. That means a solar power plant, a solar farm of solar panels put into space. Instead of relying on the [limited] day and night solar energy cycle on the ground, you could have constant sunlight delivering energy via a microwave or laser link to the ground.

There are few dedicated helium refineries in the world right now, but nowhere is truly prepared for the future when it comes to this particular element. And despite some balancing out of helium market in recent months, some estimates suggest that we could still run out completely of this most valuable element within the next one to 3 generations. In the 1980s, a proposal was put forward to overcome this impasse. If the Moon could be exploited not for bulk materials intended for use in distant space colonies, but for something of greater value here on Earth, if the Moon produced something worth tens of millions of dollars per ton, then it would be worth industrializing for that reason alone. The candidate wonder substance was Helium-3.

Lunar samples brought back to Earth from the Apollo 11,12,14-17 missions and the Luna 16 and 20 missions showed that 3He is present in the lunar regolith from over 4 billion years of bombardment from the solar wind. That’s a clear evidence that not all the wind coming from the Sun reaches interstellar space. A part of it reaches the surface of planets, satellites, and asteroids, which lack a magnetic field to repel it. Another part ends up being absorbed into the lunar regolith. The solar wind contains Helium-3, an isotope that is the ideal fuel for fusion reactors, and is increasingly difficult to find on Earth.

After reviewing Apollo soil sample analysis in 1985, researchers from the University of Wisconsin’s Fusion Technology Institute (FTI) first proposed the use of lunar 3He to generate clean and economical nuclear power. FTI researchers estimated that there could be at least 1 million tonnes of 3He within the first 3 meters of depth into the lunar surface.

Nuclear fusion produces energy by fusing very light atomic nuclei and producing slightly heavier ones. In space, it powers the stars. On Earth, it fuels hydrogen bombs. In theory – and there is a theory that has excited several generations of physicists so far – fusion also offers an attractive alternative to nuclear fission, understood as an almost infinite energy resource that neither requires any infrastructure capable of producing nuclear weapons, nor produces nuclear waste. A vast international program has been developed to build such a reactor in the south of France in Cadarache which is the largest technological research and development centre for energy in Europe. The reactor is called the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) and it will operate by fusing deuterium, a stable isotope of hydrogen (2H), easily separated from seawater, with tritium, a short-lived isotope of hydrogen (3H), which will have to be produced specifically for this purpose.

There are practical reasons for creating this fuel mixture, but it is not an ideal mixture. In addition to having radioactive properties, tritium is widely used – although it is not, to be honest, absolutely necessary – in the nuclear weapons industry. And tritium-fueled reactors will emit enough neutrons to turn some parts of the reactor into low-level radioactive waste, which we will still have to get rid of somehow, anyway. Burning Deuterium with 3He instead of Tritium would avoid both problems.

Helium-3 is neither radioactive nor relevant for bombs. And fusion with deuterium produces protons, not neutrons. These protons, which have an electrical charge, can be used and then discarded without anything around them becoming radioactive. Thus, the advantage of using 3He is similar to that of solar-powered satellites: clean energy.

And if you have the right reactor, you’ll only need a hundred kilograms of 3He per year to provide the same power measured in gigawatts as solar-powered satellites. Likewise It would take just a few hundred tons per year to provide the entire current electricity demand of the Earth. But, like many such projects – perhaps even more so – this idea is deeply impractical. We simply can not do it with the available logistics and current technology status.

The Earth is for sure in great need of various types of energy obtained from non-fossil fuels. But Helium-3 seems useful for such a project only to the extent that it seeks to answer the question of how the Moon can be of use to us. But so far most people have not ask themselves such a question.

THE HELIUM-3 POTENTIAL

If we could somehow get more Helium-3 the benefits will be huge. Theoretical comparisons are eye-popping. Let’s just look at it in terms of energy, value and payoff.

As Energy = On paper, tens of tons of Helium-3 could deliver energy for entire nations for long periods. If used to generate electrical energy from nuclear fusion 1 million tonnes of 3He, fused in a D-3He reactor, could produce 19 million GW/year of electrical energy. This is ~7 times the amount energy projected to be used for the entire 21st century.

Likewise 1 million metric tonnes of Helium-3, reacted with Deuterium, would generate about 20,000 TerraWatt-years of thermal energy. The units alone are awesome: a TerraWatt-year is 1 trillion, ( 1012) power watt-years To put this into perspective, 100-watt light bulb will use 100 watt-years of energy in one year. That’s about 10 times the energy we could get from mining all the fossil fuels on Earth, without the smog and acid rain.

If we torched all our uranium in liquid metal fast breeder reactors, we could generate about half this much energy, and have some interesting times storing the waste. Used in nuclear fusion reactions Hydrogen can do that too, of course. 1 kg of hydrogen has a much higher energy density and is far cheaper to produce than 1 kg of Helium-3. However helium-3 is a safer, albeit far more expensive, option for some applications.

A general overview comparison between the 2 is shown in Table 1.

As Value = Scientists say that 2 fully-loaded Space Shuttle cargo bay’s worth of Helium-3 — about 25 tonnes worth of the gas — could power the United States for 1 year at the current rate of energy consumption. To assign an economic value, suppose we assume Helium-3 would replace the fuels the United States currently buys to generate electricity. We still have all those power generating plants and distribution network, so we can’t use how much we pay for electricity. As a replacement for that fuel, that 25-tonne load of Helium-3 would worth on the order of $75 billion today, or $3 billion per tonne.

As Payoff = Here, a guess is the best we can do. Let’s suppose that by the time we’re slinging tanks of Helium-3 off the moon, the world-wide demand is 100 tonnes of the stuff a year, and people are happy to pay $3 billion per tonne. That gives us gross revenues of $300 billion a year.To put that number in perspective: Ignoring the cost of money and taxes and whatnot, that rate of income would launch a moon shot like our reference mission every day for the next 10,000 years. At that point, we will have used up all the Helium-3 on the moon and had better start thinking about something else.

For years now multiple laboratory experiments have proved that Helium can indeed do all these as presented above, yet technologically we are still on long way to go, in trying to figure out first of all how to make nuclear fusion commercially feasible and later on how to mine 3He from the Moon. That’s something for a distant future. However that futuristic prize is one reason politicians and planners are paying attention and start bringing ideas about how this can turn into a profitable business, even though workable Helium-3 fusion reactors remain, for now, speculative.

Leave a comment