Helium is an inert gas, is super light, is the second most abundant element in the universe (after hydrogen), yet on Earth, Helium is scarce, is a non-renewable resource and is very expensive to produce.One of its isotopes even more rare an precious is Helium-3. If we could somehow get more Helium-3, our dream about interplanetary trips could become realty. If we could also figure out how to make nuclear fusion technology commercially available, then Helium can propel our spaceships at super high speeds. We could visit Mars the same as we can visit any place on Earth. This dream belongs to the future, for now we are still dreaming. But let’s have a look how this could work.

HOW HE-3 COULD BE USED IN A SPACECRAFT FROM BOTH A SAFETY AND POWER EFFICIENCY PERSPECTIVE?

First things first, nuclear fusion can be super hot. Deuterium + 3He fusion reactions are approximated to take place well in excess of at least 100 million°K with some estimates stating the conditions for the fusion can as high as around 600 million °Kelvin. That’s up to 40 times higher than the Sun’s core temperature (which is around 15 million K).

Obviously there is no material that can withstand this temperature, so in order to contain such reaction it’s likely that a Tokamak is the only solution and this would have to be constructed.

Just for starters, a Tokamak is a torus shaped machine (as shown in Fig 2) which use powerful magnetic field that can contain thermonuclear fusion reaction. Like that the magnetic field will prevent the high energy byproducts of the fusion from damaging and melting the surrounding ship components. It also helps that the fusion of Deuterium and 3He doesn’t release those dangerous high-energy neutrons which are trickier to handle since they can’t be contained within a magnetic field due to their lack of charge.

Aside from safety, power is also important; after all we need electricity to sustain many of the spaceship’s functions. Typically nuclear reactions on Earth produce electricity by using the heat released from fusion to heat up water, such as the Fusion process using Deuterium + Tritium, which occur at much lower temperature (around 50 million °K). When the water boils steam is released and this steam can be used to rotate a turbine that generates electricity by altering the magnetic fields around the coils, it is rotating within but this usually only results in about 33 to 40% of the nuclear energy successfully being converted to usable electricity.

On the other hand, If we use 3He instead of Tritium (3H) then the fusion reaction becomes “aneutronic”. That means the reaction between D and 3He does not produce high-energy neutrons that damage reactor walls and cause radioactive waste. This is a significant advantage because it reduces the need for heavy shielding and minimizes the material wear and radioactivity issues associated with high-energy neutrons. Likewise no water steam is needed and of course rotation turbines are not necessary anymore. A big drawback in this case is the enormously high temperature need for a successful reaction.

To collect the energy from such reaction there could be another way though. Because D-3He fusion releases a lot of its energy in the form of charged particles (protons) a process called “Direct Collection” can be used to convert the kinetic energy of this charged particles into electrical energy.

Without going to much in detail for now, it’s good to know that there are different types of direct collection devices that could be incorporated into our spaceship. Such devices could be: a Venetian blind collector, a Beam collector, a cyclotron resonance collector, a traveling wave Direct Energy converter, and a magneto-hydrodynamic generator. All these collectors utilize various mechanisms such as electric and magnetic fields, grid structures and positive and negative potentials to separate ions in the fusion byproducts from their electrons. These ions are then collected on high voltage plates which can be used to generate an electrical current.

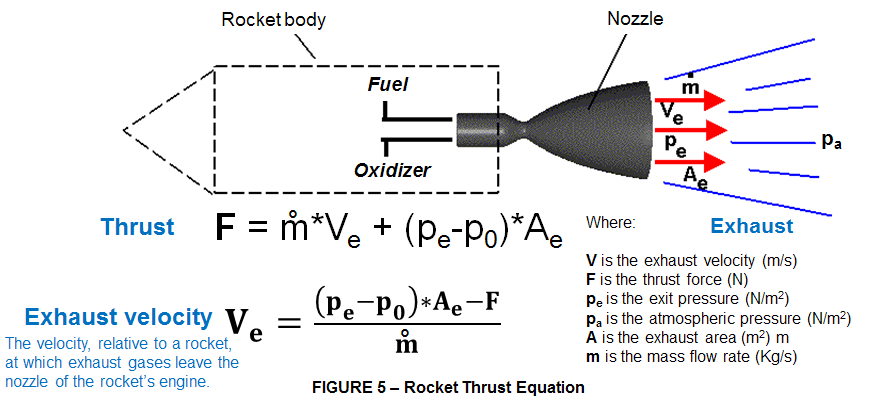

It Is likely one of these devices or a combination of these devices can be used in conjunction with each other to maximize the efficiency of the energy conversion. Estimates state that up to 70% of the fusion energy can be converted into electricity using these techniques making it far more efficient than the steam turbine as regularly used for D-T fusion. The D + 3He reaction is of particular interest for rocket propulsion, since all the products are charged particles. This means the they can be directed by a magnetic field exhaust nozzle.

The potential of 3He is massive. For now, we don’t have it yet but little progress has been already made. Anyways, this is a complex work and there is still a lot work to do until this technology is feasible. Is also important to understand that while D-3He is aneutronic, if you mix a bunch of Deuterium and Helium-3, some of the deuterium is going to be wayward and insist upon fusing with other deuterium instead of helium-3 like you want. And sadly D-D fusion reactions do produce neutrons. In theory it is possible to use spin-polarized 3He in the fusion fuel to absorb the neurons.

In particle physics, spin polarization is the degree to which the spin, i.e., the intrinsic angular momentum of elementary particles, is aligned with a given direction. If this method is used to make sure the D-3He fusion is clean of neutrons,then you will get less energy out of each gram of fusion fuel, but with the advantage of a lot less deadly neutron radiation. In practice is expected that D-3He fusion gives off maybe 5% of its energy as neutrons. A bigger worry is that bremsstrahlung x-rays are also radiated accounting for at least 20% of the fusion power.

Bremsstrahlung is a type of electromagnetic radiation, known as ” braking radiation”, produced when a fast-moving charged particle, like an electron, suddenly slows down or is deflected by another charged particle, typically an atomic nucleus. This interaction causes the particle to lose kinetic energy, which is emitted as an X-ray photon. This process is a fundamental mechanism for generating X-rays in radiology, astrophysics, and other fields.

To minimize the amount of x-rays emitted during the process, you need to run the reaction at 100 keV per particle, or 116 million °K. If it is hotter or colder, you get more x-rays radiated and more heat to deal with. This puts your maximum exhaust velocity at 7.600.000 m/s, giving you a mass flow of propellant of 34.6 g/s (grams/second) at 1 terawatt output, and a thrust of 263.000 N/TW (Newtons per terawatt). In turn, this could provide 1G of acceleration to a spacecraft with a mass of at most 26,300 kg, or 26.3 metric tons. If we say we have a payload of 20 metric tons and the rest is propellant, you have 50 hours of acceleration at maximum thrust. Note that this is insufficient to run a 1 G brachistochrone. You must burn at the beginning for a transfer orbit, then burn at the end to brake at your destination.

A 1G brachistochrone = is a theoretical spacecraft trajectory that uses a constant 1G (9.81 m/s2) acceleration to travel the fastest possible path between two points. The spaceship would accelerate continuously to the halfway point, then decelerate for the second half of the journey. This approach is considered the fastest possible trajectory for a given acceleration so that it would dramatically reduce travel times to nearby planets.

For example, using current chemical rocket propulsion, a trip to Mars takes between 5 and 10 months, with an average of about 7 months. Yet using the 1G brachistochrone approach, for a future technology, scientists are currently developing advanced propulsion systems, such as Photon Propulsion Systems, that could potentially enable a trip to Mars in just a few days. This rapid transit would offer the added benefit of providing a constant 1G artificial gravity environment within the spacecraft, enhancing crew comfort and mitigating the effects of weightlessness.

While theoretically advantageous, the practical implementation of a 1G brachistochrone trajectory faces significant challenges. Current rocket propulsion technologies are not capable of sustaining such high levels of acceleration for extended periods due to the immense fuel requirements. The development of advanced propulsion systems, such as fusion rockets or maybe matter-antimatter drives, would be necessary to achieve the sustained thrust required for this type of trajectory. Probably 3He fusion could help as well.

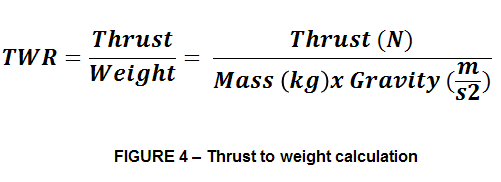

In terms of thrust, fusion reactions such as D+3He do indeed have a lower thrust to weight ration than traditional chemical fuels like liquid H and O. Thrust-to-weight ratio is a dimensionless quantity that compares an engine’s or vehicle’s thrust to its weight, indicating performance, acceleration and climb rate. It is calculated by dividing the thrust by the weight, A higher ratio indicates greater acceleration and maneuverability, while a lower ratio can be found in larger commercial aircraft.

Or we can say that the thrust-to-weight ratio is the ration of the thrust force of the spacecraft as it accelerates to the weight of the spacecraft itself. It can be either a maximal or peak, average, or minimum thrust-to-weight ratio.

Most fliers use the average value, but the minimum can be just as important when determining if a flight might be stable. A TWR ratio greater than 1 means the vehicle can lift off vertically. For spaceships of course a higher thrust-to-weight ratio is more desirable. However even if the TWR value is lower in case of D-3He fusion, it is also worth mentioning that the exhaust velocity of fusion reactions using 3He, is far greater than that which is provided by chemically powered means. This means that 3He is far more efficient as a fuel source.

In case of a 3He-powered rocket, the exhaust velocity would depend on the specific propulsion method used, but it would generally be lower than a rocket using more energetic propellants other than traditional ones.

At this point it’s just a question of size and scalability for a spacecraft as well as what materials should be used in the construction to ensure it can handle the immense heat as well as any potential radiation and don’t forget the rigorous amount of testing and experimentation needed to make sure these systems are viable on a spacecraft. At the end of the day the most important fact facing us is that the road to a fusion-based propulsion future and space exploration is filled with many engineering and scientific bridges that need to be crossed. We are just not there yet.

Leave a comment