Transportation means propelled by an engine (cars, planes, boats etc.), refrigerators, machine building industry and comfortable homes. How did humanity ended up being depended of all these? Well… the answer is already there since the Earth exist. It is given by Mother Nature and it comes from the clouds. It took a long time until humans figure out what going in on up there, and started asking: Why there are clouds in the sky? why rain occurs?

Let’s dive deep and learn what’s going on up there.

Clouds start off as wet laundry on a line, as a puddle on the pavement, as a glow of perspiration on your upper lip, as part of a vast ocean of water. Every second, some of the water (H2O) molecules leave wet laundry, puddles, upper lips, oceans, and other bodies of water, and make their way into the air. The boiling point of water is known to be = 100ºC, denoted as the temperature at which pure liquid water turns into a gas water (vapor) at sea level. Following this line, you might conclude that liquid water always turns into vapor whenever the temperature of 100°C is reached. In reality is not always the case. Hence, the following 2 questions are legit:

- How does liquid water become a gas without reaching its boiling temperature?

- What’s the point of defining the boiling point of water, if water can cheat and dry laundry and upper lips, evaporate puddles, and denude oceans autonomously, at much lower temperatures?

As it turns out, the definitions of solids, liquids, and gases are not as clear-cut as they might seem, and the game that scientists play, of categorizing the world and making neat distinctions between different things, is constantly being sabotaged by the complexity of the universe.To understand how water cheats the system to create clouds, we have to look at rain.

Rain is a natural phenomenon entirely linked to the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics, which is governed by the term called Entropy.

WHAT IS THE ENTROPY?

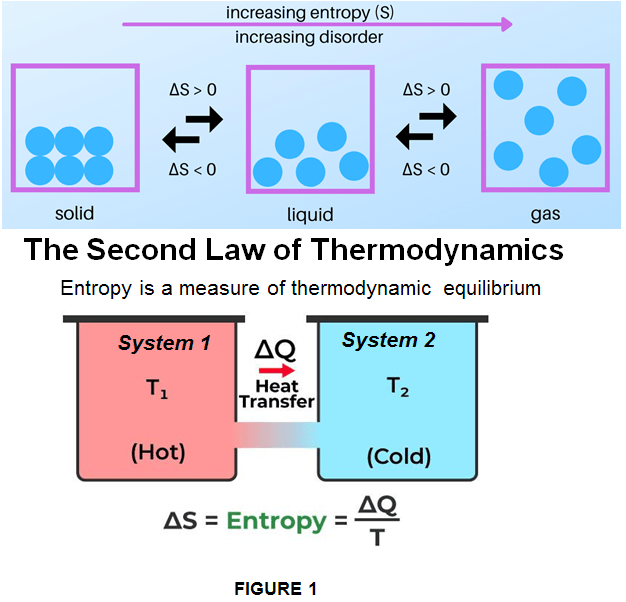

Entropy is the metric which measures the amount of disorder (randomness) of a thermodynamic system.

The movement of molecules of a substance is known as randomness. Each time this occurs between 2 systems, it yields a heat transfer. A system can either generate or absorb heat, yet at one point both system finds themselves in a thermodynamic equilibrium and the heat transfer stops. This means 3 things:

- At thermodynamic equilibrium (same temperature) –> heat flow stops

- All systems tend to go from low entropy to high entropy

- Everytime heat is exchanged entropy goes up (the availability of heat declines)

We can say that Entropy is the metric which measures the impurity of something or in other words you can say that checking entropy in a dataset is a 1st step to do before you solve the problem. As shown in Figure 1, the entropy is mathematically represented as a function of state of a themodynamic system described as a variable is given by formula: dS = DQ/T

where :

- dS = entropy ;

- DQ = the amount of heat reversibly absorbed or generated by a system

- T= temperature of the system.

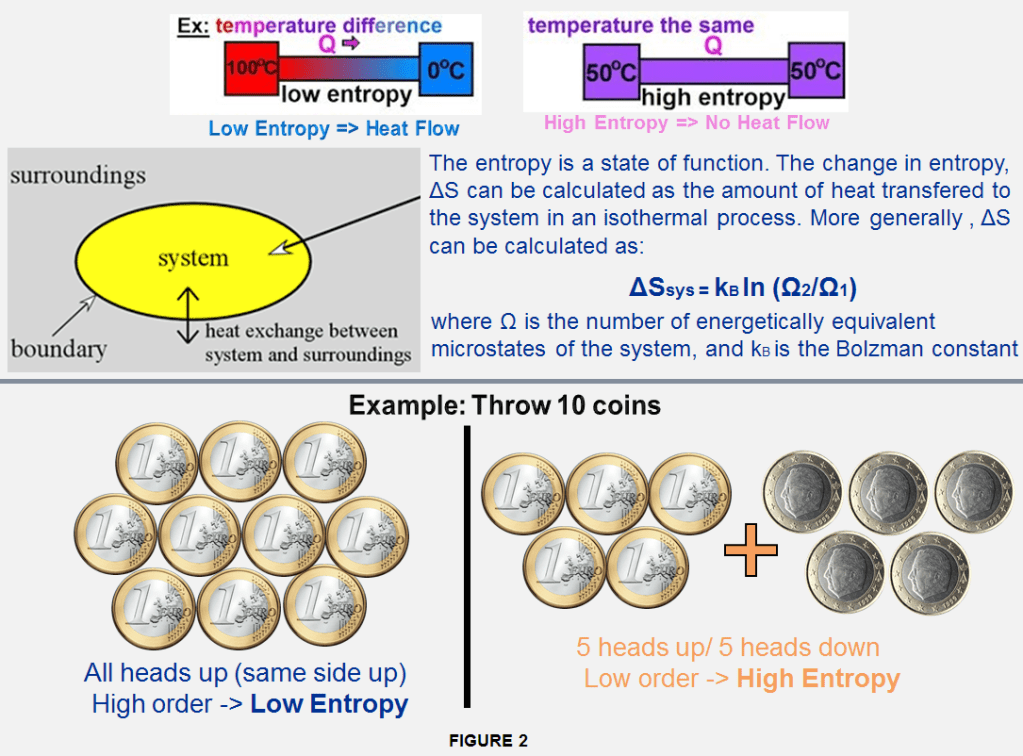

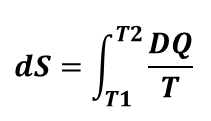

For an accurate measurement, the system which modifies its temperature reversibly from temperature T1 to T2 the entropy variation can be defined as:

Which means that the Entropy for such a system has the same value for any reversible transformation in the system between its initial and final states. Therefore for a system that exchanges heat with its surrounding environment, the total variation of entropy associated with this process is made as a sum between the entropy of the system and the entropy of the surrounding environment:

dS= dSsyst + dSenv

HOW ENTROPY WORKS?

Rain is one great example to see the entropy at work.The principle of rain works exactly the same with the principle of drying your clothes after you’ve washed them. Let’s observe how this process goes;

The water clinging to your laundry on a clothesline is a lot much below a temperature of 100ºC, but it is in contact with air. The molecules in the air bombard your washing, crashing into it as they move chaotically; occasionally, in all the mayhem, a H2O molecule pings off to become part of the air. It takes some energy to do this, as the bonds that attach the H2O molecules to your wet clothes have to be broken. Taking the energy away from your clothes cools them, but it also means that if the H2O molecules are floating around in the air were to collide again with your washing, they would gain energy by sticking to it, thus making it wetter again. So on average you might think that more water would stick back onto your clothing than would be carried away by the air currents of the wind. But here’s where entropy comes into play.

Because the amount of air billowing around your laundry is so great, and the number of water molecules is so low, the chances of a water molecule finding its way back onto your favorite cotton T-shirt is small. Instead, it is more likely to be whizzed up into the atmosphere. This propensity of the world of molecules to get jumbled up and spread out is measured by the entropy of the system. Increasing entropy is a natural law of the universe, and it opposes the forces of condensation that bond the water back onto your washing. The colder the temperature and the less exposed your laundry is to the wind, the more you tip the balance in favor of condensation, and your washing stays wet. In contrast, by hanging your washing on a line on a warm day, you tip the balance in favor of entropy, and your clothes get dry.

Exactly in the same way, Entropy also takes care of puddles in the street, dries your bathroom after you’ve been in the shower, and removes the sweat from your body on a hot day. All in all, entropy seems very convenient, and generally quite helpful, given how much we like having dry clothes and bathrooms, and cool bodies. But that same benevolent force also drives the killer clouds that strike us down in the thousands every year by throwing their lightning bolts around, reminding us who’s really the boss in our atmosphere.

Now in theory the entropy modification dS has the interestiong property of being null (dS = 0) for a reversible process. Yet in practice most systems are irreversible which means that the entropy is bigger than zero (dS > 0).

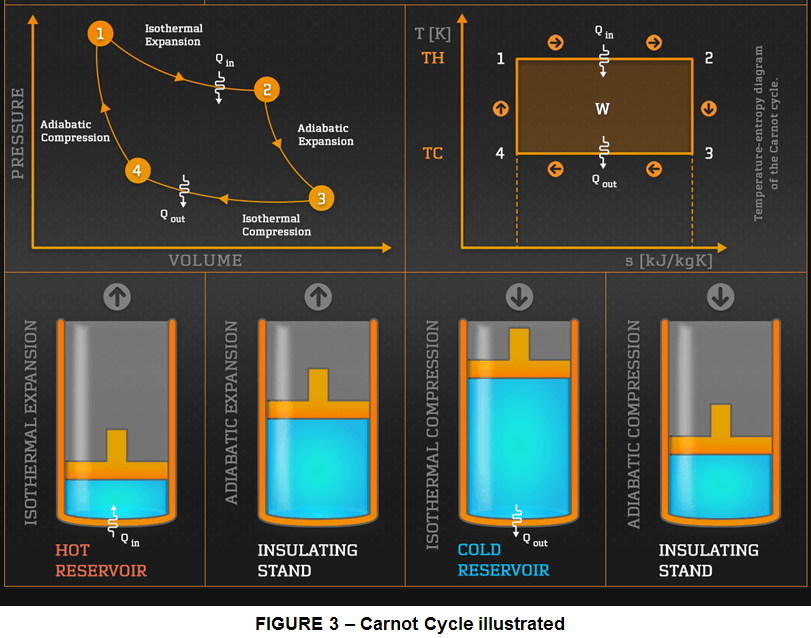

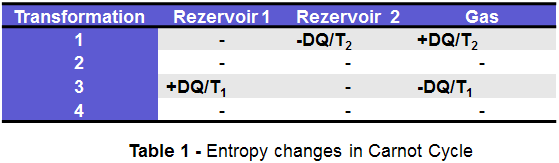

To illustrate this, let’s consider 2 big heat reservoirs, as Reservoir 1 at temperature T1 (COLD Reservoir) and Reservoir 2 at temperature T2 (HOT Reservoir), where of course the T2> T1. The reservoirs are brought in contact with each other for a short time and a small amount of heat DQ passes from T2 to T1. Let’s consider that both reservoirs are so big that there is no temperature change for none of them.The Entropy modification cannot be done directly because the process is irreversible hence the equations applied for a reversible process are not valid anymore.

Therefore, to understand how Entropy works in practice, is necessary to construct an imaginary reversible process that leads to entropy changes of the reservoirs. (The entropy being a state property, the chosen route is not important as long as continuity criteria is fulfilled): for this a quantity of ideal gas is placed in contact with the reservoir 2 (HOT) at temperature T2, allowing it to expand isothermally (transformation 1); this absorbs the heat quantity DQ from reservoir 2 (HOT); then the gas is isolated and adiabatically expanded until its temperature decreases to T1 (transformation 2), then is put in contact with the reservoir 1 (COLD) and is isothermally compressed until it gives off the amount of heat DQ to reservoir 1(COLD) (transformation 3) , and finally the gas is removed from contact with reservoir 1 and adiabatically compressed until it reaches again the temperature T2 (transformation 4).

This process represents the Carnot Cycle, first proposed by french military scientist Sadi Carnot in 1824. In this process an ideal gas is subjected to 4 transformations: 2 isothermal (at constant temperature) (transformation 1 & 3) and 2 adiabatic (no heat transfer) (transformation 2 & 4).

The Entropy changes associated with all these 4 transformations are summarized in table 1.

Hence we can see from the Carnot Cycle that the entropy change of the reservoirs is indeed:

ds= DQ/T1 – DQ/T2 = DQ(T2-T1)/T1T2.

Becasue T2 > T1, it results a dS > 0, which corresponds with what the 2nd law of thermodynamics needs for irreversible processes.

Based on this 2nd law of thermodynamics using entropy we can not only use it to manufacture things, but we can also create and handle the technology that allows us to manipulate weather conditions. With it, we can control how and where the rain should fall. With other words We can induce artificial rain. The tech is called cloud seeding.

Leave a comment