One of the most iconic engineering marvel ever build by humans is the thing that makes us fly: the plane.

For some people flying is not really a comfortable experience, for others it’s an interesting adventure, usually a pleasant one. However as humans we all know that we cannot fly naturally like birds do. We must rely on the objects we build in order to help us fly. Personally I enjoy traveling by plane, yet like for any human I guess, to me it doesn’t matter how many times I experience turbulence when I travel by plane, I can never seem to stop the seeds of panic forming in my brain.

Rationally, I know the wings of the plane aren’t going to snap – I have traveled across the world on long distances, simply because the flying today is the most reliable, fast, save and convenient way of traveling. Accidents can happen of course but are rare compared with other means of transport. But knowing how these planes are build and what we are able to do with them, this is beyond extraordinary, it´s amazing.The wings of the plane and many other component parts in the aircraft structure are glued to make the assembly and they are being mechanically tested in this condition with remarkably good results.

Over the years, I´ve learnt not to talk about aircraft being glued together to other passengers; they generally don´t find that reassuring. But it’s a fact, planes and any other flying objects are mainly assembled using GLUE by already advanced technology called Adhesive Bonding.

Glue as structural assembly material is not a new invention, For thousands of years, glue has been used for instance in the production of veneered furniture or wooden musical instruments. Yet, the primary boost in the use of adhesives came with the advent of synthetic polymeric materials with improved mechanical properties since 1925. Glues starts off as liquids and then, generally speaking, transform into a solid, creating a permanent bond. However, unsticking is likewise often as important as sticking.

Historically, the designers of classic musical instruments, like Antonio Stradivari, known as the greatest violin maker of all time, used animal glue to construct their instruments.This would have allowed Stradivari to unstick any joints that were faulty during production and so produce almost perfect instruments. Today, in order to repair a wooden instrument, craftspeople unstick the joints with stream. This causes the bond between the glue and the wood to weaken and then dissolve. Thus the wood comes away undamaged and clean, extending the lifetime of the instrument, and increasing its value. Indeed most people who work in furniture restoration use animal glues precisely because they can be easily unstuck using heat.

But when it comes to making wings, heat can be real problem, or at least that´s what legend tells us. Let’s recall a little bit the famous legend story of King Minos in ancient Greece.

“King Minos, who ruled the Mediterranean island of Crete and was given a very beautiful snow-white bull from the sea god Poseidon. King Minos was instructed to sacrifice the bull to honour Poseidon but he sacrificed another bull instead, because he did not want to kill the more beautiful one. To punish him, Poseidon made King Minos´wife fall in love with the bull, and the offspring of that union was a creature that was half man and half bull – a Minotaur. This Minotaur grew up to be a terrifying beast that ate humans, and so King Minos got his master craftsman Daedalus to construct a prison for the Minotaur in the form of an elaborate maze called the Labyrinth. To prevent Daedalus from telling others about the secrets within, King Minos imprisoned him in a tower along with his young son, Icarus. Daedalus, though, was a hard man to contain. He constructed wings by glueing feathers together with wax: one pair for himself and one for Icarus. On the day of their escape Daedalus warned his son not to fly too close to the sun. but during their flight Icarus was so exhilarated that he began to soar higher and higher. The wax melted, the feathers came unstuck, and Icarus fell to his death”.

Now, If you are wondering whether a modern aircraft could come unglued as it flies higher and higher, I should point out that the myth of Icarus defies logic. By flying higher, Icarus would have experienced colder temperatures, not hotter ones. Temperature decreases by 1°C for every 300 meters of altitude you gain, because the atmosphere is cooled by the radiation of heat into space At 12.000 meters, the altitude a passenger plane flies, the temperature is at approximately -50°C, a temperature at which all waxes are solid. I should also say at this point that modern aircraft are not glued together using wax – nowadays we have much better glues.

The sticky tape pioneered by American inventor Richard Drew in 1925, although a useful invention, is not the technological innovation that led to the modern aircraft. That came from another American chemist, called Leo Baekeland, who succeeded in making one of the first plastics.

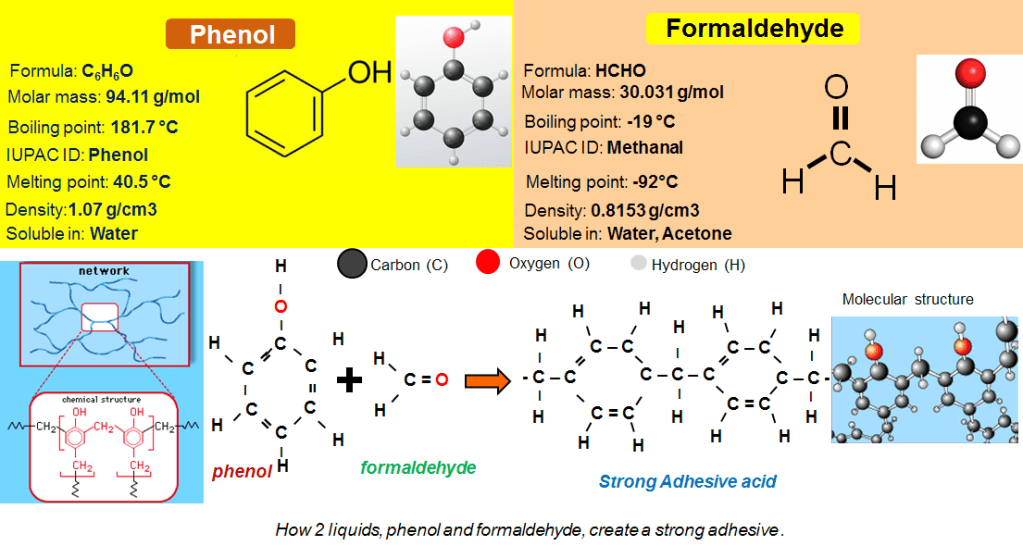

Leo Baekeland made his plastic by combining 2 liquids. The first was based on phenols, the main constituent of birch resin, and the other ingredient was formaldehyde, an embalming fluid. These 2 liquids react together to produce a new molecule that has a spare bond for more phenols to attach themselves to, which in turn produces bonds for still more reactions with more phenols, and eventually the whole liquid (if you get the proportions right) is chemically locked together into a solid.

In other words, the reaction makes one giant molecule, and all the bonds holding it together are permanent, so whatever object you’ve created will be hard and strong. Baekeland used this new plastic to create a number of objects such as the new telephones that had just been invented. This was , of course, immensely useful and made Baekeland a fortune. But it had another impact. Chemists realized that the phenol and formaldehyde could be mixed and applied to the interface between 2 things – gluing them together as it hardened.This was the beginning of a whole new family of glues called 2-part adhesives, which were stronger than anything that had come before. The more people used these 2-part adhesives, the more they understood just how useful they were.

First of all, the different components – phenol and formaldehyde – could be stored in separate containers, and thus remain liquid until they needed to be used. And then, beyond that, you could alter their chemical composition through additives, and make them better or worse at wetting and then sticking to different materials, such as metals or wood. This new type of glue had a big effect on the world of engineers. They returned to thinking about plywood, first developed in ancient Egypt. If you made plywood using a 2-part adhesive perfectly designed to bond with wood, you’d have plywood that was neither held together with the weak bonds of animal glue, nor sensitive to water. But, for this new plywood to take off, it still needed to be driven by a strong market demand. The simultaneous development of the aircraft industry provided just that.

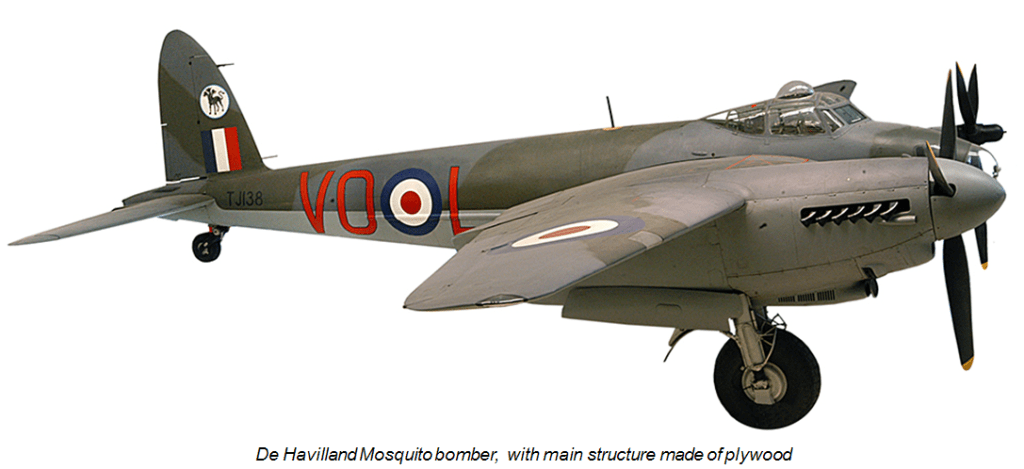

In the early 20th century, most planes were made of wood, but because of wood grain they were liable to crack. Plywood was the perfect solution – it could be moulded into aerodynamic shapes and was both reliable and resilient thanks to the new 2-part adhesives. The most famous plywood aeroplane ever built was the De Havilland Mosquito bomber.

When it was introduced in the Second World War, it was the fastest aircraft in the sky. Because it could outrun every other plane, it wasn’t even outfitted with defensive machine guns. It remains, to this day, perhaps the most beautiful plywood object ever made. Its elegance and sensuousness come from the ability to mould the plywood into complex shapes while the glues set, a property that’s maintained its popularity with designers for decades.

After the war, plywood continued to revolutionize our world – this time with furniture. But while plywood furniture stood the test of time, aeronautical engineering had to move on. After the war, aluminium alloys became the pre-eminent material for making aircraft, not because they were stronger by weight than plywood, or even stiffer by weight than plywood. No, aluminium won out because it could be more reliably manufactured, pressurized and certified, especially as planes became bigger and started to fly higher.

It´s very hard to stop plywood from absorbing water or from drying out. Plywood aircraft that spent a lot of time in arid countries would eventually dry out, causing the material to shrink and putting stress on the glued joints. Similarly , when aircraft were deployed in very wet places, the plywood would expand (or even rot), again compromising the safety of the aircraft.

Aluminium doesn’t suffer from these defects; in fact, it´s incredibly resistant to corrosion, and as such was the basis of aircraft structures for the next 50 years. But it is by no means perfect – it isn’t stiff enough or strong enough by weight to create truly lightweight, fuel-efficient aircraft. So even when aluminium aircraft production was at its height, a generation of engineers were scratching their heads about what the ideal material for the skin of an aeroplane would be. They wondered whether it was another metal, or something else entirely. And yes, indeed there was another material. Specifically a composite material: The Carbon Fiber composite.

Carbon fibre looked promising since it was 10 times stiffer by weight than steel, aluminium or plywood. But carbon fibre is a textile, and, at the time, no one could make a plane wing out of it. The answer, it turned out, was epoxy glue. Versus traditional glues used to assembly wood structures, these epoxies have a major advantage of being chemically very versatile. Chemists can attach different components using epoxy glue, which allows it to bond to different materials, such as metals, ceramics and yes, carbon fibre as well. This making them largely used to build big, lightweight, mechanically very stable and strong aircraft structures.

Leave a comment