The Periodic Table currently contains 118 elements. Individually these elements have unique properties and structures. Yet in most cases single elements are rarely used, some of them are artificially created in so tiny quantities that many of their characteristics are still unknown. Usually most elements combine between them to create new materials with new properties quite different than than each element separately. There are also cases when the same element creates different structure combining with other atoms of his own. Like for example the most famous example: Carbon, which can be found naturally either as graphite or as diamond. Such different arrangements of atoms in a crystalline structure made from the same element are called allotropes (or polymorphs).

This means that the graphite in your school pencil and the diamonds found in jewelry are made of the same atoms (carbon atoms), but the carbon atoms are arranged in different crystal structures in graphite versus diamond. None of these crystalline combinations have anything to do with being eatable. However such material actually exist. That’s CHOCOLATE.

There are 6 different kinds of crystals in chocolate, but not all of them look good and taste good. So then the question is: how do you get the chocolate that you buy at the store? The simple answer is: Through material science!

Now let’s see what exactly does this mean!?

Each of the 6 crystals in chocolate are made of the same chemicals, but they have a different shape/structure. As I’ve already mentioned we call crystals with the same composition but different structure polymorphs. In the case of chocolate, each of the 6 crystal polymorphs has a different melting temperature, so by controlling the heating and cooling rates of molten chocolate, we can melt the crystals we don’t want to obtain the type of chocolate crystals we do want.

THE 6 POLYMORPHS OF CHOCOLATE

Types I and II crystals, as they are called mechanically are soft and quite unstable. They will, if given any chance at all, transform into the denser Types III and IV. Nevertheless they are useful for making chocolate coatings on ice creams, because their low melting point of 17°C allows them to melt in the mouth even when cooled by the ice cream.

Types III and IV crystals are soft and crumbly and have no brittle ‘snap’ when broken. The mechanical property of the snap is important to chocolatiers because it adds surprise and drama to our experience of the chocolate. For example, it allows them to create hard outer shells with which to encase soft centers, providing a textual contrast. From a psychophysics perspective, meanwhile, brittleness and the sound associated with cracking open a chocolate are linked with freshness, which again adds to the enjoyment of eating chocolate with a ‘snap’. Anyone who has tucked into a bar of chocolate expecting it to be hard and brittle only to find it gooey and melted knows just how dissapointing losing the snap can be. (Although it is fair to say that gooey chocolate has its place as well…).

For all these reasons chocolate makers tend to want to avoid Types III and IV crystals, but unfortunately they are the easiest to create: if you melt some chocolate and then let it cool down, you will almost certainly form Types III and IV crystals – this chocolate feels soft to the touch, has a matt finish and melts easily in the hand. These crystals will transform into the more stable Type V over time, but on the way they will eject some sugar and fat, which will appear as white powder on the surface of the chocolate – called bloom.

Type V is an extremely dense fat crystal. It gives the chocolate hard, glossy surface with an almost mirror-like finish, and a pleasing ‘snap’ when broken. It has a higher melting point than the other crystal types, melting at 34°C, and so only melts in your mouth. Because of these attributes, the aim of most chocolatiers is to make Type V cocoa butter crystals. Yet, this is easier said than done. They have to be created through a process of heating chocolate to a desired temperature to grow only one crystal structure (phase V), process called tempering chocolate. Type V is the crystal phase that gives chocolate its glossy, shiny appearance, its satisfying “snap” when you break it, and its smooth texture.

The diverse polymorphs are formed under different crystallization conditions. The thermodynamically most stable form, Type VI, has a dull surface and soft texture; only Type V shows the hardness and glossy surface appreciated by the consumer.

Gourmets only accept chocolate in its crystal Type V, as it is this form that has the noble surface sheen, crisp hardness and the pleasant melting sensation in the mouth.The chocolate producer must achieve the physicochemical trick of making the chocolate crystallize not in the thermodynamically most stable Type VI but in the somewhat more energy-rich Type V. If he does not succeed, the chocolate is practically unsaleable, for 3 reasons:

1 – The surface looks dull and shows a pattern reminiscent of frostwork. This renders the chocolate visually unattractive

2- Compared to form V with a melting point of 33.8 °C, crystal form VI, due to its higher melting point at 36.2 °C, melts only very slowly on the tongue and produces a coarse and sandy sensation on the tongue.

3- Crystal form VI has a soft texture. Compared to form V, biting into a bar of chocolate of form V does not feel crisp, but rather reminds of candle wax.

CONVERSION => The reason for the lower stability of crystal form V lies in the relatively loose packing of the lipid molecules, leaving empty spaces. In the solid state, crystal form V also tends to convert into the more stable form VI. The addition of milk fat retards the conversion so that the V→VI transition is less often observed in milk chocolate. At room temperature, the conversion takes place only slowly; it nevertheless limits the shelf life of chocolate to several months. Therefore, chocolate should always be stored in a refrigerated environment (15–18 °C). At higher temperature, e.g., in the sun or in a warmed up car trunk, the undesirable phase transition V→VI happens quickly, even faster than during unintentional melting and subsequent cooling. If the phase transition happens, the producer’s effort will have been in vain: The chocolate is dull, soft and melts only slowly in the mouth.

CHOCOLATE TEMPERING

Tempering chocolate is required to obtain only form V, the most desirable. This is achieved by allowing the chocolate to cool at room temperature, which leads to some of all the polymorphs except VI forming, then heating gently to just below the melting point of form V, so it is the major form remaining.

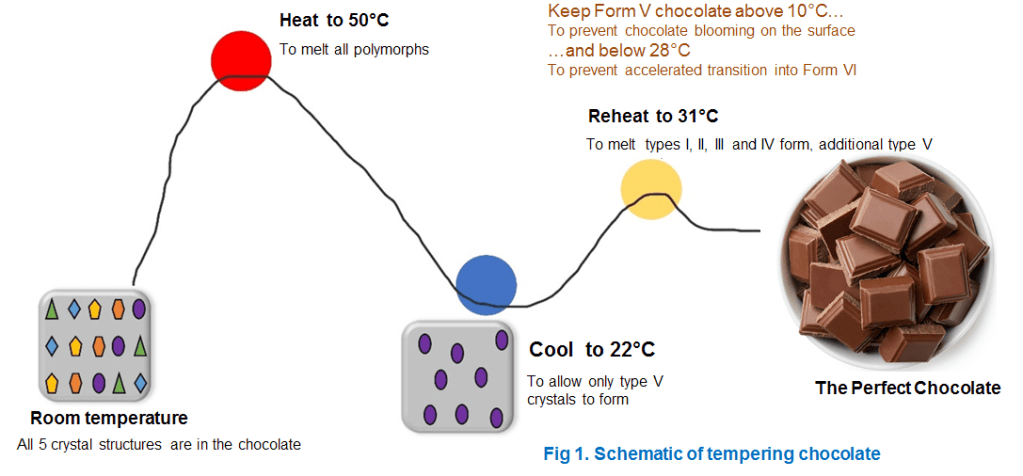

How exactly tempering works? => It’s quite simple process to follow. Just melt chocolate to 50°C. Cool it to 22°C so that only Form V is allowed to condensate at lower temperature), notice that Forms III, IV and V have similar melting points. Therefore, for best results, heat again to 31°C, which is warm enough to melt forms I,II, III and IV, then re-cool to 22°C to allow them to re-crystallise as Form V. Repeat again if greater Form V purity is desired.(see the schematic principle in fig 1)

However, there is another way to temper chocolate through introducing little bits of already tempered chocolate. These little bits of tempered chocolate act as seed crystals and initiate preferential crystal growth of phase V chocolate crystals (as shown in Fig. 2). These give the slower-growing Type V crystals a head start over the faster-growing Type III and IV crystals, allowing the whole liquid mass to solidify into the denser form of crystal structure before the Type III and IV crystals have a chance to get going.

Seed crystals are often used in ceramic and metal processing to initiate a desired crystal phase to grow. Material scientists call seed crystals nucleation sites. Nucleation sites are areas in a material that make it easy for crystals to grow. Using nucleation sites to cause preferential crystal growth is a very important process in material science as it allows scientists and engineers to optimize material properties.

When you put pure dark chocolate into your mouth and sense it start to liquefy, what you are feeling are the Type V cocoa butter crystals that are holding the chocolate together starting to wobble. if they have been cared for properly they will have spent their entire life at temperature below 18°C. Now, in your mouth, they experience higher temperatures for the first time. This is the moment they have been created for. It is their and last performance. As they warm up and reach the threshold of 34°C they start to melt.

This change from solid to liquid – a so-called ‘ transformation of state’ – requires energy to break the atomic bonds that are holding the molecules of a crystal together, thus freeing them to move around as a liquid. So as the chocolate reaches its melting point, it takes this extra energy that it needs from your body. The chocolate gets this energy in the form of latent heat, as it is called, from your tongue. You perceive it as a pleasant cooling effect, similar almost to sucking a mint. It’s the same cooling effect that is produced when you sweat, but rather that a solid becoming a liquid, instead a liquid (your sweat) changes state into a gas, absorbing the latent heat required to do so from your skin. Plants use the same process to cool themselves down.

In the case of cocoa crystals, the coolness of the chocolate melting is accompanied by the sudden production of a warm thick liquid in the mouth, and it is this wild combination of impressions that is responsible for the unique feel of chocolate in the mouth – it is the beginning of the hot chocolate experience.

What happens next is that the ingredients of the chocolate once bound together by the rigid cocoa butter matrix, are now free to flow to your taste buds. The grains of the cocoa nut, which were once encapsulated in the solid cocoa butter, are now released.

Dark chocolate usually contains 50% cocoa fat and 20% cocoa nut powder (referred to as “70% cocoa solids’ on the packaging). Almost all the rest is sugar. 30% sugar is a lot. It’s the equivalent o putting a spoonful of sugar in your mouth. Nevertheless dark chocolate isn’t overly sweet; sometimes it’s not sweet at all. This is because at the same time that the sugars are released by the melting cocoa butter, so are chemicals known as alkaloids and phenolics from the cocoa powder. These are molecules such as caffeine and theobromine, which are extremely bitter and astringent.

They activate the bitter and sour taste receptors and complement the sweetness of the sugar. Balancing these basic tasted to give the chocolate a rounded flavour enhancer, as well as adding another dimension to modern chocolates, has in turn led to chocolate being used as an ingredient in savory dishes: it is the basis of the Mexican dish pollo con mole, which is chicken cooked in dark chocolate.

Although we may not always think of chocolate as a common scientific material, tempering chocolate is actually quite similar to synthesizing and processing metals and ceramics. Tempering chocolate is a great way to learn about the important role crystal structure plays in material properties. Even the desired properties of chocolate such as its smoothness and shininess are obtained through controlling the crystal structure of chocolate. By performing this activity, we can all learn to be material scientists in our kitchens!

Leave a comment