Asphalt (bitumen) composites are the most common material used to surface roads, with 95% of EU roads paved with asphalt mixtures. Its success is due to a combination of factors that have been widely studied, such as:

- it creates a safe and robust road surface for driving when combined with stone aggregates and appropriate polymer binders;

- road surfacing can be carried out rapidly and without complex machinery;

- it has good acoustic properties and so muffles the sounds of traffic;

- it is robust, repairable and indeed has the ability to self-repair.

However asphalt composites do degrade over time due to the effects of road usage, oxidation, loss of volatiles, moisture damage, and various other factors. This degradation leads to increased stiffness of the road surface, cracks forming, stripping, raveling, loss of aggregate, and development of pot-holes.

Despite a stipulated minimum lifetime of 40 years, the resurfacing of roads is estimated to cost £2 billion per year in the UK alone. Increasing the life of roads has the potential to reduce environmental and financial costs associated with road closures and the congestion they cause. Therefore one approach taken to increase the life of asphalt roads has been to enhance their self-healing properties. Actually making them become “smart”. So the big question is How Asphalt can become a “smart” material?

“Smart Materials” already exist for some time, but we still have a lot learn more about them. In the category of such materials a notable mention are the “Shape Memory” alloys and “Functionally Graded Materials”. Yet more recently something new has attracted a huge interest: “The Self-Healing materials”. What I consider super interesting here is the fact that actually these materials are there for centuries, we just didn’t know how to use them. One such material which can indeed have self-healing effect is the Asphalt.

WHY DO WE ACTUALLY NEED SMART ASPHALT?

Here is why: Living on a fluid planet, the one thing we can be certain about is change: sea levels are rising, the Earth´s mantle is flowing moving the continents, volcanoes erupt creating new lands and destroying others; hurricanes, typhoons and tsunamis continue to batter our coastlines, reducing cities to rubble and so on.

In the face of this future it seems only rational to build our homes, roads, water systems, power stations and indeed airports – all the stuff we rely on to live a dignified and civilized life – to withstand damage. This stuff needs to be strong and tough to survive earthquakes and floods, yes, but it´d be even better if we could design our infrastructure so it would repair itself, allowing our cities to be more nimble and resilient in the face of environmental change.

This may sound far-fetched, but, in fact, it´s what biological systems have been doing for million of years. Consider a tree: if it´s damaged in a storm, it can repair itself by growing new limbs. Likewise, if you cut yourself, your skin heals itself. So then: Could our cities become similarly self-healing?

The answer is of course YES.

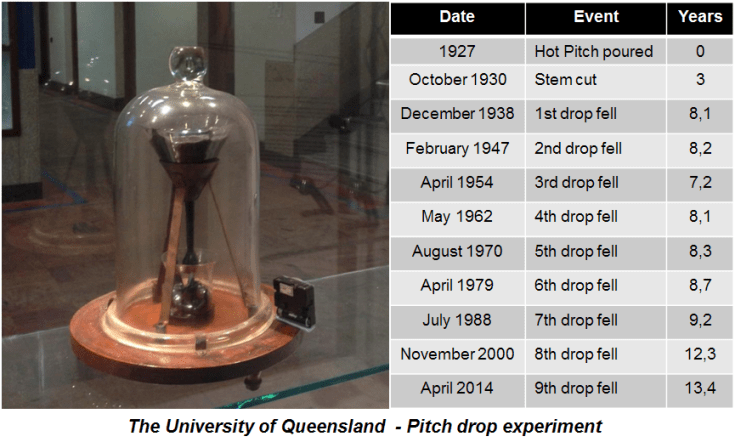

In 1927 Professor Thomas Parnell of the University of Queensland conducted an experiment to see what would happen to black tar if it was left to settle in a funnel. What he found was that, over days, it behaved like a solid, staying just where he put it. But over months and years it started to creep and behave like a liquid. Indeed, it flowed down the funnel and started to form droplets.

The 1st drop fell in 1938, the 2nd fell in 1947, the 3rd in 1954 and so on, with the 9th drop falling in 2014.This is surprising behavior from a material that seems so solid when you drive over it in your car. That´s asphalt, but asphalt is just tar mixed with stones. So what´s going on?

Tar is a much more interesting material than anyone initially thought – materials scientists included. Extracted from the ground or produced as a by-product of crude oil, it seems to be nothing more than boring, black sludge. But in reality it´s a dynamic mixture of hydrocarbon molecules that formed over millions of years from the decayed molecular machinery of biological organisms. The decay products are complex molecules which although not part of a living system anymore, nevertheless self-organize themselves within tar, creating a set of interlinked structures.

At normal temperatures the smaller molecules inside the tar have enough energy to move through its internal architecture, which gives the material fluidity. So tar is a liquid, albeit a very viscous one: it is 2 billion times more viscous than peanut butter, which explains why Professor Parnell´s tar has taken so long to drip through the funnel.

The Asphalt self-healing, mainly restoring mechanical properties of asphalt through crack closing, is an ability conferred by the asphalt component bitumen. Correlation between self-healing rate and bitumen viscosity and the influence of filler content, filler type, temperature, amount of bitumen and bitumen modification suggests that the closing of cracks is a flow process. Hence, it is mainly assumed that bitumen is responsible for the recovery of diminished or lost properties due to damage.

Tar´s characteristic pungent smell comes from molecules which contain sulphur (S), an element often associated with smelly organic substances. When you walk or drive past engineers laying down a new road surface, you´ll see and smell them heating up tar, which gives the molecules more energy to move, and thus to flow. But the extra energy also allows more of the molecules to evaporate into the air and so the material becomes smellier, just as drinks become more aromatic when they are heated up. A smelly liquid might seem an idiotic thing to build a road with, but engineers add stones to the material, creating a composite substance: part liquid and part solid -similar, in fact, to the structure of peanut butter, which is made of a lot of ground-up pieces of peanut all held together by an oil.

The strength and hardness of the stones supports the weight of vehicles driving over the asphalt and also helps the road resist damage from exposure. Cracks do sometimes open up if the forces exerted on the road get to be too high, but they do so between the stones and the tar that´s gluing them together. This is where the liquid nature of tar comes to the rescue: the tar flows in and reseals these cracks, allowing the road to repair itself and last far longer than a purely solid surface ever would.

Of course, as road users, you´ll have noticed that there is a limit to their self-repairing properties: roads eventually do get old and start to disintegrate. Temperature is partially to blame. If the temperature gets below, say, 20°C, then the liquid tar becomes so viscous that it cannot reflow and heal the cracks as they appear. And beyond that, over time, oxygen from the air reacts with molecules on the surface of the tar and alters their properties, again making it more and more viscous, and less and less able to seal up cracks. Over time , the road skin will change colour and become less fluid, just as your skin becomes less flexible and drier as you age. This is when you´ll see small potholes form, which, unless tended to, grow and grow and eventually destroy the road surface entirely.

Scientists and engineers across the world are busily developing strategies for increasing the life of roads and thus reducing traffic jams. In the Nederlands for example, a group of engineers is studying the effect of incorporating tiny microscopic fibers of steel into tar. This of course does not alter the mechanical properties of the road much, but it does make them more powerful?

When the material is exposed to an alternating magnetic field, electric currents flow inside the steel fibers, heating them up. The hot steel, in turn heats up the tar, making it locally more fluid, allowing it to flow and heal any cracks. Essentially, they´re supercharging the self-healing properties of tar, and also countering the challenges of winter´s cold temperatures. The technology is being tested on stretches of motorway in the Nederlands now, using a special vehicle that applies a magnetic field to the road as it drives along. The idea is that, in the future, all vehicles could be fitted with such a device, so anyone driving on a road would also be revitalizing it.

Another way to address tar´s natural loss of fluidity is to replenish its lost volatile ingredients – the molecules that make it flow. The easiest way of doing that would be to apply a special kind of cream on to the road surface – essentially a moisturizing cream, just like the ones we use on our skin. A more sophisticated version of this method is being tested by a group in Notthingam University, led by Dr. Alvaro Garcia. They put micro-capsules of sunflower oil into tar. These remain intact inside the material until micro-cracks form, causing the capsules to rupture. The oil, once released, locally increases the fluidity of the tar and thus promotes flow and self-healing capabilities.

The results of their studies show that cracked asphalt samples are restored to their full strength two days after the sunflower oil is released. This is a dramatic improvement. It is estimated that this has the potential to increase the lifespan of a road from 12 years to 16 years with only a marginal increase in cost.

Asphalt of the Future

Until it’s time for hover cars, asphalt roads are likely to stick around. And the industry plans to keep innovating in product and production. For example the recent breakthroughs like autonomous rollers and equipment, as well as the increased use of virtual reality for training. As asphalt experts get better at handling big data, they can use it for production and placement to improve efficiencies in real time. One day, he could even see intelligent pavements with nano-sensors in the roads providing feedback on how the pavement is behaving and lasting. Our roads are going to get a lot smarter. We’ve already got the technology to really improve the experience of the riding public.

Leave a comment