Aerogels are synthetic, porous, ultralight, dry materials (unlike “regular” gels you might think of, which are usually wet like gelatin dessert). The word “aerogel” refers to the fact that aerogels are derived from gels – effectively the solid structure of a wet gel, in which the liquid component has been replaced with air or other gas. Because the pores and struts that make up the aerogel’s internal structure are so small, lots of weird physics happens there, that gives aerogels apparent superpowers, or to be technical, extreme material properties. And which “superpowers” an aerogel has, it largely depends on what exactly the aerogel is made of and its density. Therefore Aerogels are a diverse class of porous, solid materials that exhibit an uncanny array of extreme materials properties. Let’s take a closer look at the most interesting ones.

ULTRALOW DENSITY

Something all aerogels have in common is extremely low density, typically ranging from ~0.6 g/cm3 to as low as 0.00018 g/cm3 (yup, that’s 0.18 mg/cm3). That lower value represents the world record for the world’s lightest solid material, which is a formulation of aerogel made of graphene, called aerographite which in its basic form has a density of only 0.00018 g/cm3. For comparison, the density of water is 1g/cm3 where most plastics are about 1.2 g/cm3 and air is about 0.00123 g/cm3.

The most commonly used aerogels are Silica Aerogels, materials which have a density of about 0.0019 g/cm3 almost as light as air and it’s 500 times lighter than polystyrene. In fact, the lowest density solid materials that have ever been produced are all aerogels, including a silica aerogel that is usually produced only three times heavier than air, and could be made even lighter than air by evacuating the air out of its pores or replaced it with helium (He). In fact an aerogel that light could float in the air—until air diffuses back into its pores. Now you might ask, Could one somehow seal the outside of an evacuated graphene aerogel and make a flying device of some sort?

Well.. I would say not really. Aside from it being very difficult to make ultralight aerogels and having generally low mechanical strength, if you do the math, adding a sealant to the outside of the aerogel would add so much weight that you really wouldn’t have much of a floating object anymore. But maybe, you might have a better idea, prove me wrong !

Aerogels are around 1,000 times less dense than a far more well-known silicon-based material: glass. But even at those densities, it would take 150 brick-sized pieces of aerogel to weigh as much as a single gallon of water! Or for instance if Michaelangelo’s David were made out of an aerogel with a density of 0.020 g/cm3, it would only weigh about 2 kg! Typically aerogels are 95-99% air (or other gas) in volume, with the lowest-density aerogel ever produced being 99.98% air in volume. Aerogels are open-porous solid materials (that is, the gas in the aerogel is not trapped inside solid pockets) and have pores in the range of <1 to 100 nanometers (billionths of a meter) in diameter and usually <20 nm.

HARDNESS & ELASTICITY

Well…In general all aerogels are pretty hard & fragile. But for this property it largelly depends which one do you have. Inorganic or Organic?

To the touch, an inorganic aerogel (such as a silica or metal oxide aerogel) feels something like a cross between a Styrofoam peanut, that green floral potting foam used for potting fake flowers, and a Rice Krispie. Inorganic aerogels are friable and will snap when bent or, in the case of very low density aerogels, when poked, cleaving with an irregular fracture.

Organic polymer aerogels on the other hand, are less fragile than inorganic aerogels and are more like green potting foam in consistency in that they are squish irreversibly. Carbon aerogels for instance, which are derived from organic aerogels, have the consistency of activated charcoal and are very much not squishy.

ULTRAHIGH STRENGTH-TO-WEIGHT RATIO

One remarkable property of aerogels is their incredible high strength-to-weight ratios. Depending on their density, as mentioned earlier, a typical silica aerogel could hold up to 2000 times its weight in applied force and sometimes even up to 4000 times. But this only holds if the force is gently and uniformly applied. Also, since aerogels are so low in density it doesn’t take much force to achieve a pressure concentration equivalent to 2,000 times the material’s weight at a given point The amount of pressure required to crush most aerogels with your fingers is about what it would take to crush a piece of Cap’n Crunch cereal. And because most aerogels as-produced are extremely brittle and friable (that is, they tend to fragment and pulverize), as a result, structural applications of aerogels were for a long time totally impractical. For instance, the blue silica aerogels of NASA lore tend to have low fracture toughness, meaning that even though they can hold thousands of times their weight, they tend to fracture easily. As result, pinching or poking can break Classic Silica aerogels very easily.

However with the recent materials development there are several examples of remarkably strong aerogels which can withstand tens of thousands of times their weight in applied force. So aerogels can be made strong and even flexible, enough that aerogels can now be used as structural elements.

A class of polymer-crosslinked inorganic aerogels called x-aerogels are such materials and can even be made flexible like rubber in addition to being mechanically robust. One type of x-aerogel made from vanadia (vanadium oxide) is extraordinarily strong in compression with the highest compressive strength to weight ratio of any known type of aerogel and rivals that of materials such as aerospace-grade carbon fiber composites. Regardless of composition, most types of aerogel can be made stronger simply by making them denser (between 0.1 and 0.5 g/cm3), however only at the expense of their light weight and ultra-low thermal conductivity.

Likewise, a new class of mechanically strong aerogels called Airloys made by the company called Aerogel Technologies from USA, have recently become available and exhibit the ultra-low density and superior thermal insulating properties inherent to aerogels while being strong, stiff, tough, and machinable at the same time! And not only are Airloys more robust than classic aerogels, but they can hold hundreds of thousands of times their weight in compression—lots more than even ordinary aerogels!

SUPERIOR THERMAL CONDUCTIVITY

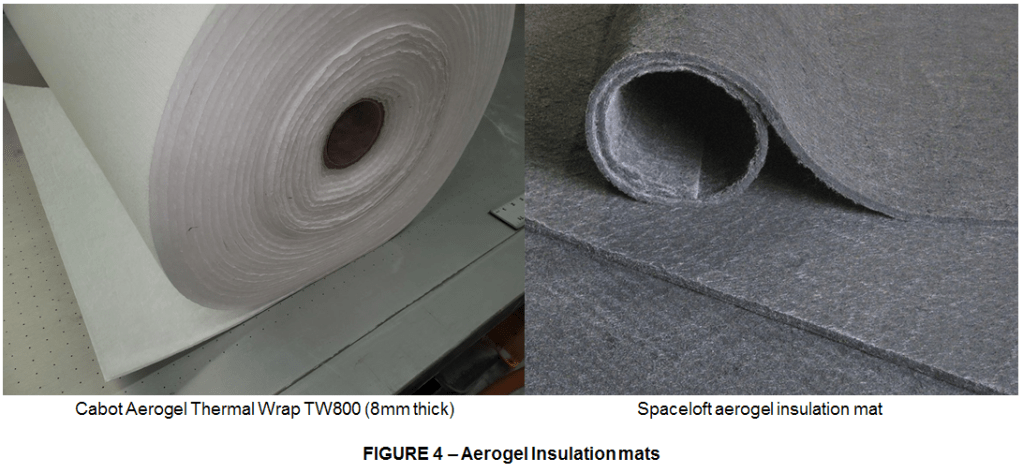

The best known superpower possessed by aerogel materials is their superior thermal insulating abilities. In fact, the world’s best insulating solids are all aerogels. A 2.5-cm-thick aerogel tile can have the same insulating ability of 15 panes of windowglass or the equivalent of 7.5 cm thick of Styrofoam. And as gorgeous as aerogel tiles may be, for real-world applications flexible fiber-reinforced superinsulating aerogel blankets such as Cabot’s Thermal Wrap and Aspen Aerogels’ Spaceloft are typically used instead and today insulate subsea oil pipelines, energy-efficient buildings, and winter apparel around the world.

Some aerogels, including silica aerogel, are not only thermally superinsulating but are superinsulating at high temperatures. This property has been used for example to save a scientist from the blast of the flamethrower from the movie Terminator 2. That’s flame temperatures of up to 700°C. Now, a blowtorch can easily become the melting point of most aerogels if it’s turned up all the way, most aerogels have great thermal protection on constant heat exposure up until 600-700°C, and it’s thermal conductivity is almost zero, but above that temperature it can become risky because normally aerogel starts to melt at 1200ºC.

But never fear! There is already good news about this too. An experimental aerogel material called Galacticlad developed by the company Aerogel Technologies from USA, it’s an aerogel that can easily survive temperature up to 2700°C, that’s 50% hotter than SpaceShuttle tile.

ULTRAHIGH SURFACE AREA

A typical piece of aerogel (let’s say a silica aerogel or a carbon aerogel) has about 700 m2/g—that means an aerogel the size of ice cube has wrapped up inside all its nooks and crannies about half a football field’s worth of surface area! What’s especially cool is that scientists can put stuff on all that surface area to make aerogels do bizarre things. One example is by reacting waterproofing agents with the skeletal surfaces of the aerogel to make waterproof, or hydrophobic, aerogels. In fact, with hydrophobic aerogel particles, you can even make yourself waterproof (don’t worry, it’s just temporary). And if an aerogel is made of an electrically conductive substance, like carbon aerogels are, you now have an awesome electrode material for supercapacitors, batteries, and desalination filters!

ACOUSTIC SUPERINSULATION

Besides keeping things toasty (or cool, depending what you’re trying to do), aerogels are excellent acoustic dampers—that is, they work as phenomenal sound proofing. Airloy aerogels, for example, are 10 to 1000 times better sound insulation than even polyurethane foam. The acoustic properties of aerogels show their great potential in sound insulation.

To date, the characterization and understanding of the acoustic behavior are limited mainly to inorganic (silica-based) aerogels and their composites rather than to polymer aerogels, synthetic or bio-based. Silica-based aerogels have demonstrated excellent sound absorption over a wide range of frequencies. Typically, conventional porous materials do not show exceptional insulation characteristics in the low-frequency range, below 200 Hz, where silica and some synthetic polymer aerogels have outperformed any state-of-the-art insulation material. Moreover, for the frequency range up to 5 kHz, aerogels show significantly higher sound transmission loss properties (e.g., 40 dB/cm for monolithic polyurea aerogels at 0.45 g/cm3 bulk density) compared to traditional state-of-the-art acoustics materials, such as polyurethane foam at similar density, which can only reach up to 5 dB.

This is another breakthrough for aerogels that makes them different from other porous materials. However, silica aerogels possess some drawbacks (e.g., the production price) that hinder, for the time being, their commercialization. Bio-based polymer aerogels are awaiting to be explored for their acoustic properties too. Therefore, an in-depth systematic experimental and theoretical investigations of a broad range of aerogels are needed to advance the development of high-performance materials for acoustic insulation. Here things are very promising as well.

Leave a comment