Matter is made of atoms and the way how they combine to create structures is fundamental knowledge for our understanding of everything in the universe. Well, just to generalize a little bit, because practically speaking this is a bit of overstatement. We are still far to understand “everything”, for example we know almost nothing about dark matter, neither too much about what’s inside of a black hole, we have little understanding about antimatter and we are puzzled by quantum physics which occur at micro scale between elemental particles. So far we’ve made a important progress in understanding of quantum physics but we still have a lot to learn. Our knowledge is more precise at macro scale but this also starts with at least a good understanding of micro world from atomic level. Atoms are not the tiniest part in which the matter can be divided, but things become clear enough if we take atoms are reference for our macro understating of materials science.

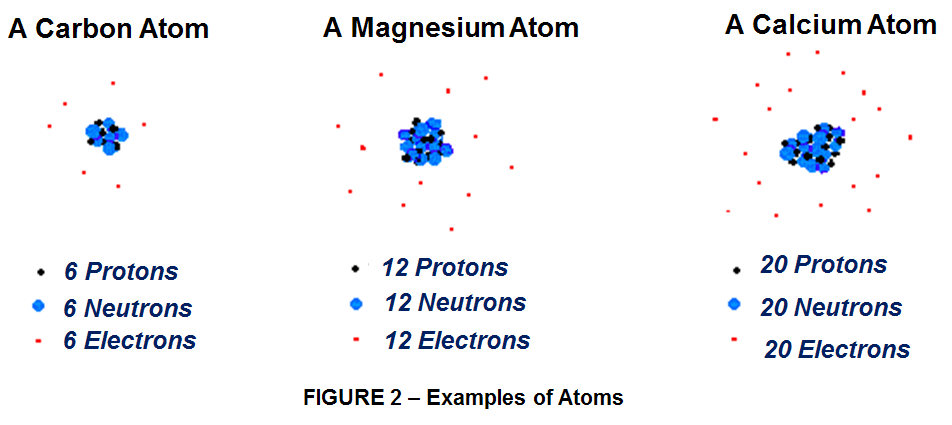

Atoms are tiny. If you print this page, you could pack 1 million carbon atoms into the dot at the end of this sentence. But don’t think of atoms as solid balls of matter. They consist almost entirely of empty space. Each has a tiny nucleus in its center made up of protons (with positive charges) and neutrons (which have no charge) bound together by the strong nuclear force. The rest of the atom is mostly empty. Orbiting the nuclei at huge distances are clouds of electrons (with negative charges), roughly one to each proton in the nucleus. Early in the 20th century, Ernest Rutherford, one of the pioneers of modern nuclear physics, described the nucleus of an atom as “the fly in the cathedral.” The scale Rutherford suggests is about right. But he was writing before the evolution of modern quantum physics, which showed that his metaphor is also misleading.

Electrons are minuscule, with about 1/1836 the mass of a proton. Quantum physics showed that we can never pin down their exact speed or position. We can tell where an electron probably is, but never exactly where it is, because any attempt to locate it will require the use of energy (imagine shining a flashlight on it), and electrons are so light that the energy used to detect them will alter their speed and trajectory. This is why quantum physicists map orbiting electrons onto a sort of “probability mist” that thickens at certain distances from the nucleus and thins out at others. The probability mist pervades most of the atomic cathedral and can seep beyond its outer walls. Chemistry is all about the trysts and the wars inside these probability mists. And there’s a lot going on. Bonds are formed and broken between protons and electrons, old ties are ended, new relationships are started, and the result is the emergence of entirely new forms of matter. Driving all this activity is the simple fact that electrons have negative charges that repel each other but attract them to the positive charges of protons, either in their home atom or in neighboring atoms. Chemists study these flirtations and rivalries and the liaisons and tensions they create as electrons hitch up to neighboring atoms to form molecules linking several atoms, sometimes millions or even billions of them, into structures more complex than the most complex star. Each molecular pattern has distinctive emergent properties, so the possibilities of chemistry seem endless. Nevertheless, the courtships have their own operating rules (sometimes as perverse as the rules of a human courtship), and these govern how the electromagnetic force can build chemical complexity. Hence the Materials Science is based on Electron rules.

Rules especially those based on numbers, often seem arbitrary. Let’ make the analogy with Sports which are a case in point. Football, is a sport game played by 2 teams each with 11 players (1 goal keeper + 10 field players) , or rugby with 15 players per team: (8 players in the tight scrum and 7 players scattered all over the field called backs) and so on for other sport games played in teams (basketball, handball, volleyball, etc,). All these game are played according to rules and they are played in a time frame. The team which scores better, wins the game. During the game few player are replaced in order to change the strategy how the game is played, bring fresh energy to the team, boost the motivation and eventually increase the chances to win.

Chemistry is also a kind of game, one in which atoms are the teams and electrons are the key players. – an ancient dance of chemical bonding where electrons determine the score. Here’s the quick version:

“You are an atomic winner if you wind up exactly 2 or 10 or 18 or 36 or 54 or 86 electrons”

Now some question are legit to ask:

- Why those numbers?

- Are they, too arbitrary?

- Are they subject to change in universes parallel to our own?

Physicists construct elaborate explanations of these “magic” numbers. It’s just the rules of the game, but in this case, the rules are built into the very fabric of our Cosmos. Like human lovers, electrons are unpredictable, fickle, and always open to better offers.They buzz around protons in distinct orbits, each associated with a different energy level. Wherever possible, electrons head for the orbits closest to an atom’s nucleus, which require the least energy. But the number of spaces in each orbit is limited, and if no places are left in the inner orbits, they have to settle for places in an outer orbit. If that orbit has just the right number of electrons, everyone is happy. This is the situation of the so-called noble gases such as Helium (atoms with 2 electrons), Neon (10 electrons), Argon (18 electrons), Krypton (36 elections), Xenon (54 electrons) and Radon (86 electrons) which you find over on the right-hand side of the periodic table. These special atoms spend their lives as isolated, free-floating loners – solitary “inert” gases, because they don’t need to rely on any other atoms to achieve their winning numbers of electrons. They don’t combine with other atoms because they are more or less content with the status quo.

But if the outer orbits of an atom are not filled, that creates awkwardness, problems, and tensions, and the endless jostling for position this causes can explain a lot of chemistry. Some electrons jump ship and head for neighboring atoms. If they do that, the atom they left will have lost a negative charge, so it may pair up with an atom that has an extra electron to form an ionic bond. By this showing clearly that most atoms just miss a magic number.

For example, Sodium, the element 11, starts off with 11 positive protons and 11 negative electrons, but it readily gives up an electron and becomes a positively charged ion. Chlorine with 17 protons and electrons, just as readily takes that unwanted electron from sodium to become a negatively charged chlorine ion. Positive sodium ions attract negative chlorine ions, mingling to create exquisite, tiny, cube-shaped crystals of table salt – sodium chloride. This is how salt is formed from atoms of sodium, whose outermost electron is usually willing to jump, and chlorine, which is often looking for an extra electron to fill up its outer orbit.

Sometimes, electrons will feel most comfortable when they are orbiting two nuclei, so the nuclei effectively share their charges in a covalent bond. This is how atoms of hydrogen and oxygen combine to form water molecules. But the molecule they form is lopsided, with two smallish hydrogen atoms gloming on to one side of a larger oxygen atom. That odd shape distributes negative and positive charges unevenly over the molecule’s surface and confuses hydrogen atoms, which often get attracted to the oxygen atoms in neighboring molecules. That attraction explains why water molecules can stick together in droplets, exploiting these weak hydrogen bonds. Hydrogen bonds play a fundamental role in the chemistry of life because they account for much of the behavior of genetic molecules such as DNA.

The periodic table features plenty of nonmetallic elements like Chlorine (Cl) or Oxygen (O) (with 8 electrons, 2 shy of the magic 10) more than willing to grab an extra electron or 2 from overstocked metals like sodium or magnesium(Mg)(with 12 electrons). Most of the elements in the periodic table adopt this kind of strategy, either giving away electrons or snapping them up to win the bonding game. That’s a good thing. If all atoms were equally happy with their original allotment of electrons, then there would be no reason to shuffle and share those electrons, no way to form chemical bonds and no pathway to our exuberantly varied material existence. In metals, electrons behave very differently. Vast crowds of electrons cruise among metallic nuclei, and that explains why metals are so good at conducting electric currents, which are really huge streams of electrons.

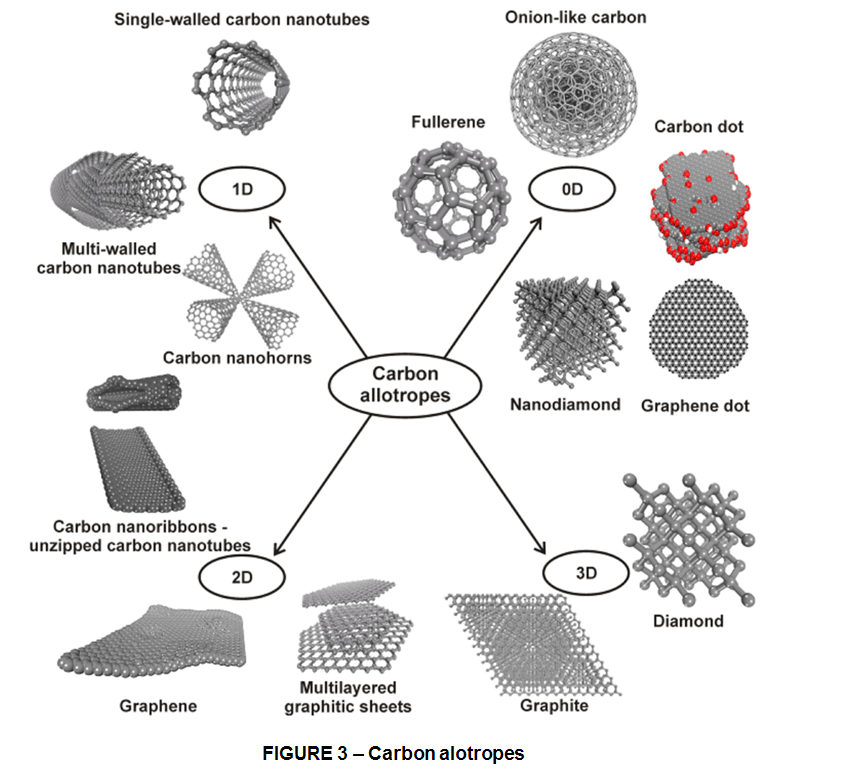

In this world of mutually beneficial electron bartering and usually friendly takeovers, Carbon holds a unique place as Element 6, smack in the middle of the periodic table, halfway between magical 2 and 10. Carbon, with 6 protons in its nucleus, is the Don Juan of these atomic romances. It normally has 4 electrons in its outer orbit, but there is room enough for 8, so you can make a carbon atom happy by removing 4 electrons from its outer shell, by adding 4 electrons, or by letting it share 4 electrons with another atom. Like a weary swimmer on a lake, treading water equidistant between 2 shores, carbon simply doesn’t “know” what to do. Should carbon go one way, seeking 4 more electrons to reach the magic number 10? Or should it head in the exact opposite direction, giving up 4 electrons to wind up at the magic number 2?

This ambiguity gives carbon a bonding advantage unknown to most other elements. This gives it a lot of options, and that is why carbon can form complicated molecules with rings, chains, and other exotic shapes. Its virtuosity explains why carbon is so important to the chemistry of life. Unlike one-trick sodium, which invariably gives up a single electron, or chlorine; which just as readily seizes that one extra electron in its struggle for atomic contentment. Element 6 enjoys many contrasting chemical roles – adding, subtracting or sharing electrons in combinations that lead to vastly more varied chemical compounds thal all of the other 100+ elements combined.That’s why carbon can create both the hardest of all known materials (diamonds) and the softest (graphite), the most vivid and varied colors and the blackest possible black, the most slippery lubricants and the stickiest glues.

The basic rules of chemistry seem to be universal. We know this because spectroscopes show that many of the simple molecules we find on Earth also exist in interstellar dust clouds. But interstellar chemistry seems to be fairly simple; no interstellar molecules detected so far have more than about a hundred atoms. And that is no surprise. After all, in space, atoms are far apart, so it’s difficult for them to hitch up with one another. Besides temperatures are chilly; so there is little of the activation energy that is needed to nudge atoms into long-term partnership. What is most striking about interstellar chemistry is that it can generate not only the simple molecules from which planets are formed, such as water and silicates, but also many of the basic molecules of life, such as amino acids, the components of proteins. Indeed, we now know that simple organic molecules are common in the universe, and that increases the likelihood that life exist beyond planet Earth.

Leave a comment