In the universe there is a lot of stuff we know nothing about or we know very little. One of them is the thing called Antimatter. We only discovered its existence almost a century ago. Today we know it is there, but more than some basic characteristic properties just enough to have a clue about it, a comprehensive in-depth understanding of antimatter the same as we know about ordinary matter, remains a topic for much more further research.

So far what we know is that antimatter does occur in the universe, but in extremely small amounts. But probably we are wrong on this, that’s hard to say. For sure we must learn more about it. However if antimatter does exists in big amounts elsewhere in the universe, then once in a while expect some to hit the earth. If this has happened in our 4 billion year history, all signs will have long gone; Meteorites leave craters around which the extraterrestrial material can still be found, but antimatter would have been destroyed in a flash. The only evidence of an antimatter strike would have been the devastating explosion when it struck and until the last millions of years no one would have been around to tell the tale. However just 115 years ago, in June 1908, something happened that has never been completely explained and which aficionados insist was the most recent example of a collision with extraterrestrial antimatter. I wouldn’t say that was really the case, but the story of Tunguska event is at least a topic of big mystery and interest in the same time.

WHAT HAPPENED ON TUNGUSKA RIVER?

Well… I don’t know. After more than a century since the event, we still have no idea what exactly happened there.

Here is what is known so far:

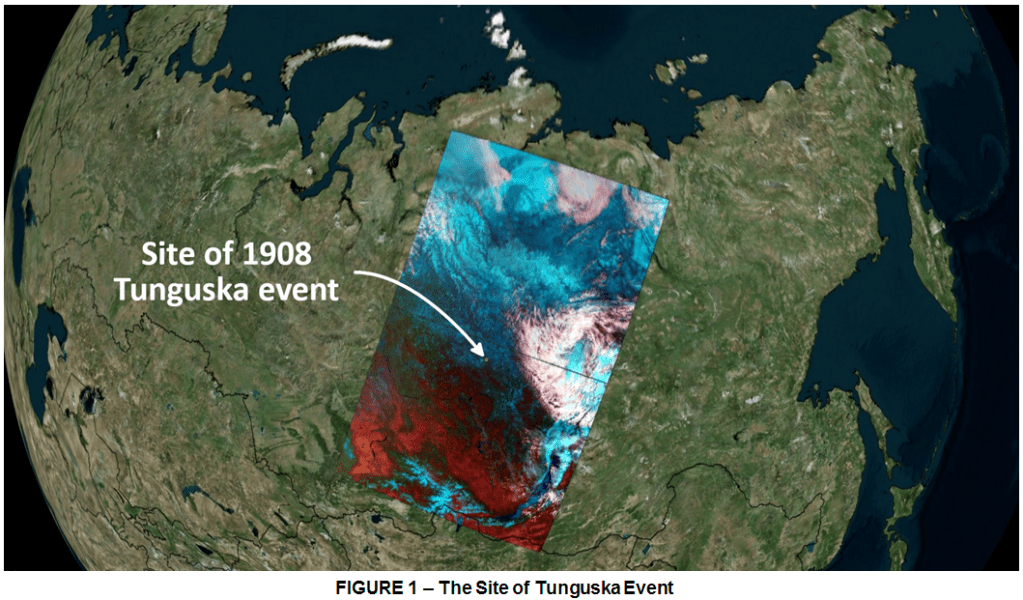

A thousand miles east of Moscow, stretching from the Arctic Sea in the north to Mongolia in the south, and from the Urals to Manchuria, is a sparsely inhabited region larger than the whole of western Europe. In the remote heart of this lonely continent is the hidden valley of the Tunguska river in Siberia, named after the Tungus people, a small ethnic group that survived by hunting bears and deer in the forests where in the summer reindeer graze among the endless pine trees. The day of 30 June 1908 dawned cloudless and sunny. At 8 o’clock in the morning Sergei Semenov, a farmer-one of the few inhabitants of the remote Siberian region of Krasnoyarsk Krai – was sitting on the steps of his house when there was a huge explosion in the sky. He later told scientists that the fireball was so bright that it even made the light of the sun appear dark and so hot that his shirt ”was almost burnt on my body” and melted his neighbor’s silverware. Even more remarkable was that, when scientists later investigated, they realized that the explosion had happened nearly 60 kilometers away from Semenov town.

Another farmer, Vassili Ilich, said that there was a huge fire that “destroyed the forest, the reindeer and all other animals”. When he and several neighbors went to investigate, they found the charred remains of some of the deer but the rest had completely disappeared. The dazzling fireball crossed from the south-east to north-west in a matter of seconds. Seismic waves were detected around the globe, and pressure waves in the atmosphere spread throughout Russia and Europe. The blast was visible 700 kilometers away, and threw so much smoke and dust into the stratosphere that sunlight was scattered from the bright side of the globe right around into the Earth’s shadow. A quarter of the way round the world in London – U.K., daylight came early as the midnight sky was as light as early evening. Had the event happened in the U.S.A. over Chicago, the light flash would have been visible as far away as Tennessee, Pennsylvania, and Toronto, while the thunder would have been heard on the East Coast, as far south as Atlanta and west to the Rocky Mountains. Two months passed before normality had returned.

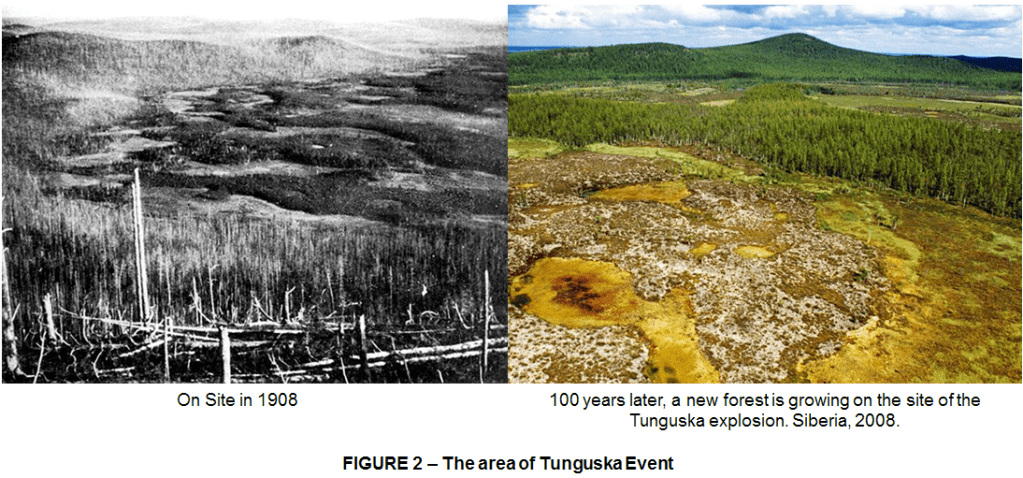

Something from outer space had hit the Earth’s atmosphere. Such things have happened in the past, as shown for example by the huge meteor crater in Arizona, which was the result of a lump of rock, a small asteroid, hitting the Earth. However the Tunguska Event, as it has become known, was different, as became apparent years later when the first adventurous investigators, led by the Czechoslovakian scientist Leonid Kulik in 1927, reached the remote site. Had it been an asteroid, a lump of rock from the solar system that had smashed into the earth, then some tell-tale hole in the ground should have been there. However, there was no sign of any crater. They discovered that immediately below the explosion was a vast mud plain as if a thousand bulldozers had cleared the forest to prepare the foundations for a city the size of London. Surrounding this bleak scene was a ring of charred tree stumps, as result this event flattened 80 million trees in the area. Beyond this the trees lay scattered like matchsticks, felled by a tumultuous hurricane, the blastwave from the explosion. Life had been totally destroyed, and remained so for over a quarter of a century. Since then, the ground has been excavated to depths of over 30 meters, but no signs of meteorite material or any physical trace of the invader have ever been found.

Whatever hit the Earth that day had vanished into thin air. In 1965 a trio of scientists comprising a physicist, a chemist, and a geophysicist examined all the evidence in the hope of determining once and for all what had happened. Examination of occasional trees that had remained standing showed traces of the blast wave that had hit. This gave an idea of the strength of the winds; the energy required to make trees burn can also be computed. There were records that showed the Earth’s magnetic field was disturbed, and seismometers had recorded the strength of the apparent earthquake. Reports of the brightness of the flash and its duration were then factored in to the calculation. They deduced that almost a million billion joules of energy had been released in a few seconds, which is similar to an hour’s energy consumption by the entire United Kingdom, and consistent with a nuclear explosion. While a man-made nuclear explosion would have been a natural suspect today, it would not have been in 1908 when nuclear physics, as we know it, was still decades in the future. If the nuclear seeds of matter were indeed involved in the catastrophe some natural cause would be called for.

Until the present day, that event is still a mystery, we simply don’t know for sure what happened. However the Prima Facie pieces of evidence in the form of the blast and the singular lack of any material remnants at the scene were all consistent with antimatter in the form of a lump of antirock as small as a meter across having been responsible, destroying everything including the nuclei of atoms. If a lump of matter is your fuel, then antimatter is the spark that will release its energy in ways that, theoretically at least, cannot be bettered in nature. This is why some have cited the Tunguska Event to have been the result of antimatter hitting the atmosphere.

COULD HAVE BEEN REALLY AN ANTIMATTER STRIKE HAPPEN IN THE TUNGUSKA EVENT?

Again, we don’t know what exactly happened. This puzzle most probably will never be solved. From as far as scientists can confirm this could be largely explained as follows:

While the Earth and planets are traveling around the Sun on widely separated orbits that are nearly circular, they are all playing chicken on the roundabout with other lumps of rock, pieces of dead comets, and asteroids whose orbits criss-cross our own. Comets are probably the oldest members of the solar system. Consisting of gravel and ice, deep frozen ammonia (NH3) and methane (CH4), many of them spend much of their time beyond Pluto in deep space where we are unaware of them. If one loops in towards the Sun, the Sun’s warmth vaporizes the ice. The resulting ejected gases and dust reflect the Sun’s light so as to appear to our telescopes, and sometimes even to the naked eye, as a bright head known as a coma.

The comet’s center may consist of 1 or 2 lumps of rock about 1,5km in diameter whereas the coma is usually bigger than the Earth, extending as much as 160.000 km across.The solar wind, high-speed particles emitted by the Sun, drive fine dust particles from the coma, forming the comet’s lengthy tail, which is the characteristic cometary shape as recorded in the Bayeaux tapestry and paintings throughout history. Fragments of comets form rings of rocks, most but not all of which are found in a belt between Mars and Jupiter. Some form elongated trails around the Sun and when the Earth passes through one of these on its annual orbit, the rubble burns up in our atmosphere and we experience a meteor shower, such as the Leonids around 12 November and the Perseids in mid-August. Sometimes larger pieces reach ground as meteorites.

The largest pieces of the comet may orbit on long after the rest have dispersed or been burned up in collisions. These extinct comet heads form some of the asteroids. The orbits of several of these cross our own, and they contain rocks that are as much as a kilometer in diameter. About once in 100 million years we chance upon a real monster. The death of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago is now believed to have been caused by a collision with an asteroid the size of Manhattan. Closing on Earth at some 40 km/s, it disrupted the atmosphere, exploded, and thundered into the ground at what today is the northern tip of the Yucatan peninsula, leaving its mark as the Chicxulub crater. This was extreme but far from unique.

Impact craters exceeding a kilometer in size pepper the planet. The famous crater in Arizona, which is over 1,6km wide and 4,8km in circumference, was caused by an impact 30.000 years ago between Earth and a lump of rock the size of an oil-tanker. So with all of the evidence of Earth being hit by rocks throughout its history and with the evidence all over the planet, what was so remarkable about the Tunguska event that led to suggestions that we had hit a lump of antimatter?

The most obvious surprise was that, had it not been for the eyewitness evidence and worldwide records of seismic activity and disturbance of the atmosphere, in other words, had this happened long ago, there would have been no permanent record to show something had actually happened at all. As I said, there was no crater; no meteoritic material from an extraterrestrial; the invader, whatever it was, had vanished in thin air. That is why Tunguska has an aura of mystery and the phenomena are all consistent with what you might expect if antimatter had hit the Earth, and been utterly annihilated.

Antimatter in comets is at most one part in a billion of the stuff in the solar system, so the likelihood of Tunguska being due to a lump of antirock is small. However, for those who want to appeal to the possibility of a one-off chance event, more conclusive proof can be provided. As forensic science can expose the culprit at a crime scene, so can it reveal a lot about what happened in Tunguska a century ago. The possibility that Tunguska was indeed an antimatter strike isn’t immediately dismissed as a media fancy. Scientists have carefully evaluated the pros and cons of this hypothesis, and in doing so have used the years of experience gained with antimatter at labs like CERN in Geneva- Switzerland.

These experiments showed that when antiprotons annihilate matter, the products include gamma rays and pions. That is the primary result but a secondary and important discovery is that when these hit surrounding material, lots of neutrons are ejected. So if antimatter had annihilated in the atmosphere, the surrounding forest would have been hit by a blast of neutrons, which in turn would have produced lots of radioactive carbon-14 in the trees. Studies of tree rings show how much carbon-14 is produced each year. There was nothing unusual in the Tunguska region in 1908, which runs counter to the idea that antimatter was the source of the explosion. The favored conclusion is that the impact was due to a piece of a comet. The dust tail of a comet, which is directed away from the Sun, would have been pointed in a north-westerly direction when the comet hit at that time of the morning and explains the unusual luminescence of the night sky over Russia and Western Europe, and its absence in the United States to the east, in the week following the fall. The radiation flash that burned the watching farmers and melted the silverware is also in accord with a comet exploding.

The initial estimates showed the energy released was similar to that in a nuclear explosion, but very large chemical explosions in the air can create intense shock waves that will heat bodies when they hit them and produce the effects found at Tunguska. The power of impact happened that day in the area, was 1000 times greater that the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. The chemicals within a comet, once released, react with the air and also produce energy. The net result is a vast amount of heat, a flash of light, and the set of experiences reported by the farmers. The damage was from the blast, which felled the trees, caused fires, and killed animals. The explosion of a comet would have used up its energy in the atmosphere to leave no lasting record on the surface. The lights, dust, seismic shocks are all consistent with the scenario that a comet melted explosively when it hit the atmosphere, far above the Earth’s surface.

There have almost certainly been many such events in the past, and with no one to have witnessed them we are unlikely to find evidence for them. The ones we do know of are the true monsters which, having done damage in the atmosphere during their fall, have enough rock left at landfall to leave a permanent imprint. For all the excitement that Tunguska created, in the course of world history it was rather small. Comets are out there and sometimes we bump into one. When we do, the results are very much like what happened in Tunguska. It has happened in the past, and will again in the future. The Tunguska event was indeed dramatic, but there is no reason to suspect 100% that the drama implies that a lump of antimatter hit the Earth one midsummer day a century ago or indeed ever. If such event will happen again in the near future, with our current state of the art in technology development we could probably understand more, but meanwhile what happened in Tunguska remains a mystery.

Leave a comment