Fire and explosions are exaclty what the Sun does. On Earth fire doesn’t occur naturally that much like on the Sun, but we have it since the planet Earth exist. It is in volcanoes, in lightning strike or in wildfires ignited by the sun’s heat. Human species discovered fire so long ago that we can never know for sure when that time was. According to many archeological studies is claimed that the 1st evidence of control of fire was done by a memner of Homo species range some 1,8 to 2 milion years ago, much before the evolution of Homo sapines, it could be Homo Erectus or even earlier. We just don’t know for sure. But what we do know 100% is at least that 3 key components are needed for a fire or explosion to occur and eventually spread, you need: Oxygen, a Source of Ignition (heat) and FUEL. These components are commonly refered to as the FIRE TRIANGLE. So in order for a fire to be extinguished, at least one of these components of the “fire triangle” must be removed.

FIRE is the effect of a chemical reaction known as combustion, which occurs between oxygen in the air and some sort of fuel that’s been heated to its flashpoint, or the lowest temperature at which it will ignite. OXYGEN is the naturally occurring element needed for igniting and sustaining a fire (21% of the Earth’s atmosphere by composition is Oxygen). When burning fuel is exposed to oxygen from the air, a chemical reaction occurs that releases heat and generates combustion. FUEL is any kind of flammable material, including trees, grasses, shrubs, and even houses. These materials emit a vapor. HEAT (as source of ignition) brings these fuels to their flash point, causing the vapor to evaporate and mix with oxygen. Not all fuels keep the fire burning with the same intensity on the same period of time. It all depends on their flammability. In this article, I’ll be talking about Hydrogen. And obviosly comes the quesion: How flammable is Hydrogen?

The simple and straight forward aswer is:

Hydrogen is highly flammable. It is the most explosive and flammable substance in existence.

Now let’s look at this more in details. Hydrogen, as highly flammable fuel, mixes with oxygen whenever air is allowed to enter a hydrogen vessel, or when hydrogen leaks from any vessel into the air. Ignition sources take the form of sparks, flames, or high heat, even spark from electrostatic discharge between 2 persons is sufficient to ignite hydrogen. With other words hydrogen ignites quick and burn powerful and fast. Compared with other fuels which have similar properties, hydrogen is by far the most powerful and flammable substance. To understand exaclty how fire generated by hydrogen occurs let’s take a look at its flammability characteristics. These are:

- The Flammability Range

- The Auto-Ignition Temperature

- The Flashpoint

- The Burning Speed

- The Ignition Energy

- The Octane Number

- The Flame Characteristics

- The Quenching Gap

FLAMABILITY RANGE

The flammability range of a gas is defined in terms of its Lower Flammability Limit (LFL) and its upper flammability limit (UFL).

The LFL of a gas = is the lowest gas concentration that will support a self-propagating flame when mixed with air and ignited. Below the LFL, there is not enough fuel present to support combustion; the fuel/air mixture is simply too lean.

The UFL of a gas is the highest gas concentration that will support a self-propagating flame when mixed with air and ignited. Above the UFL, there is not enough oxygen present to support combustion; the fuel/air mixture is too rich.

In case of Hydrogen FIRE, a stoichiometric mixture occurs when oxygen and hydrogen molecules are present in the exact ratio needed to complete the combustion reaction. If less hydrogen is available than oxygen, the mixture is lean so that all the fuel will be consumed but some oxygen will remain. If more hydrogen is available than oxygen, the mixture is rich so that some of the fuel will remain unreacted although all of the oxygen will be consumed.One consequence of the UFL is that stored hydrogen (whether gaseous or liquid) is not flammable while stored, due to the absence of oxygen in the cylinders. The fuel only becomes flammable in the peripheral areas of a leak where the fuel mixes with the air in sufficient proportions. Practical internal combustion and fuel cell systems typically operate lean since this situation promotes the complete reaction of all available fuel.

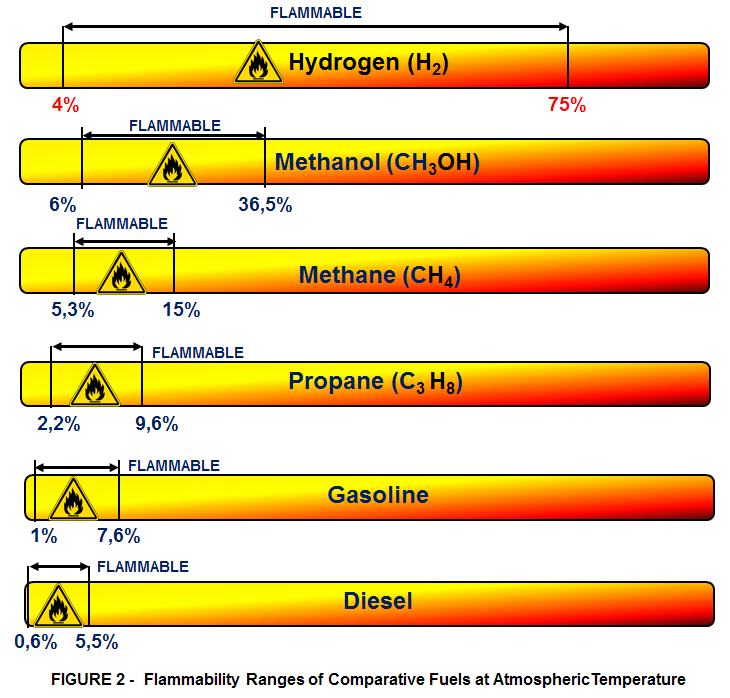

Hydrogen is flammable over a very wide range of concentrations in air (from 4% to 75%) and it is explosive over a wide range of concentrations (from 15% – 59%) at standard atmospheric temperature. The flammability limits of comparative fuels are illustrated in Figure 2.

The flammability limits increase with temperature as illustrated in Figure 3. As a result, even small leaks of hydrogen have the potential to burn or explode. Leaked hydrogen can concentrate in an enclosed environment, thereby increasing the risk of combustion and explosion.

In case of Hydrogen EXPLOSION, two related concepts are the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and the Upper Explosive Limit (UEL). These terms are often used interchangeably with LFL and UFL, although they are not the same.

The LEL is the lowest gas concentration that will support an explosion when mixed with air, contained and ignited.

The UEL is the highest gas concentration that will support an explosion when mixed with air, contained and ignited.

An explosion is different from a fire in that for an explosion, the combustion must be contained, allowing the pressure and temperature to rise to levels sufficient to violently destroy the containment. For this reason, it is far more dangerous to release hydrogen into an enclosed area (such as a building) than to release it directly outdoors.

AUTO-IGNITION TEMPERATURE

The autoignition temperature is the minimum temperature required to initiate self-sustained combustion in a combustible fuel mixture in the absence of a source of ignition.

In other words, the fuel is heated until it bursts into flame. Each fuel has a unique ignition temperature. The autoignition temperature depends on gas concentration, pressure, and even the surface characteristics of the vessel. For hydrogen, the auto-ignition temperature is relatively high at 585 ºC. This makes it difficult to ignite a hydrogen/air mixture on the basis of heat alone without some additional ignition source. The autoignition temperatures of comparative fuels are indicated in Table 1.

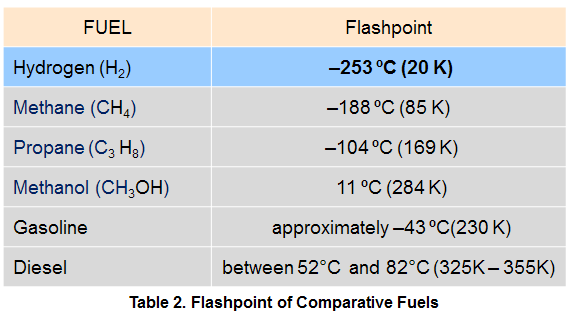

FLASHPOINT

All fuels burn only in a gaseous or vapor state. Fuels like hydrogen and methane are already gases at atmospheric conditions, whereas other fuels like gasoline or diesel that are liquids must convert to a vapor before they will burn. The characteristic that describes how easily these fuels can be converted to a vapor is the flashpoint.

The flashpoint is defined as the temperature at which the fuel produces enough vapors to form an ignitable mixture with air at its surface.

If the temperature of the fuel is below its flashpoint, it cannot produce enough vapors to burn since its evaporation rate is too slow. Whenever a fuel is at or above its flashpoint, vapors are present. The flashpoint is not the temperature at which the fuel bursts into flames; that is the auto-ignition temperature. The flashpoint is always lower than the boiling point. For fuels that are gases at atmospheric conditions (like hydrogen, methane and propane), the flashpoint is far below ambient temperature and has little relevance since the fuel is already fully vaporized. For fuels that are liquids at atmospheric conditions (such as gasoline or methanol), the flashpoint acts as a lower flammability temperature limit.

BURNING SPEED

Burning speed it the speed at which a flame travels through a combustible gas mixture.

Burning speed is different from flame speed. The burning speed indicates the severity of an explosion since high burning velocities have a greater tendency to support the transition from deflagration to detonation in long tunnels or pipes.

Flame speed is the sum of burning speed and displacement velocity of the unburned gas mixture.

Burning speed varies with gas concentration and drops off at both ends of the flammability range. Below the LFL and above the UFL the burning speed is zero. The burning speed of hydrogen at 2.65–3.25 m/s is nearly an order of magnitude higher than that of methane or gasoline (at stoichiometric conditions). Thus hydrogen fires burn quickly and, as a result, tend to be relatively short-lived.

IGNITION ENERGY

Ignition energy is the amount of external energy that must be applied in order to ignite a combustible fuel mixture.

Energy from an external source must be higher than the auto-ignition temperature and be of sufficient duration to heat the fuel vapor to its ignition temperature. Common ignition sources are flames and sparks. Although hydrogen has a higher auto-ignition temperature than methane, propane or gasoline, its ignition energy at 0.02 mJ is about an order of magnitude lower and is therefore more easily ignitable. Even an invisible spark or static electricity discharge from a human body (in dry conditions) may have enough energy to cause ignition.

Nonetheless, it is important to realize that the ignition energy for all of these fuels is very low so that conditions that will ignite one fuel will generally ignite any of the others. Hydrogen has the added property of low electro-conductivity so that the flow or agitation of hydrogen gas or liquid may generate electrostatic charges that result in sparks. For this reason, all hydrogen conveying equipment must be thoroughly grounded.

Flammable mixtures of hydrogen and air can be easily ignited.

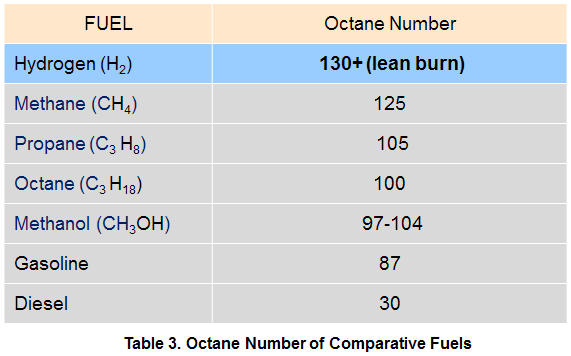

OCTANE NUMBER

The Octane Number describes the anti-knock properties of a fuel when used in an internal combustion engine. Knock is a secondary detonation that occurs after fuel ignition due to heat buildup in some other part of the combustion chamber.

When the local temperature exceeds the autoignition temperature, knock occurs. The performance of the hydrocarbon octane (C8H18) is used as a standard to measure resistance to knock, and is assigned a relative octane rating of 100. Fuels with an octane number over 100 have more resistance to auto-ignition than octane itself. Hydrogen has a very high research octane number and is therefore resistant to knock even when combusted under very lean conditions. The octane number of comparative fuels are indicated in Table 3.

The octane number has no specific relevance for use with fuel cells.

FLAME CHARACTERISTICS

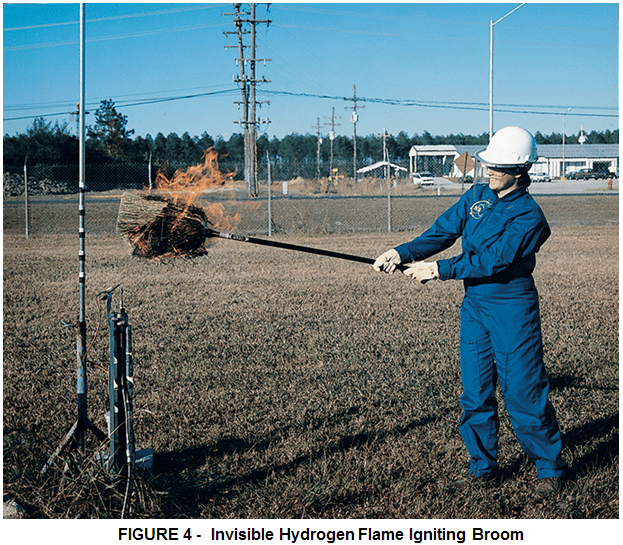

Hydrogen flames are very pale blue and are almost invisible in daylight due to the absence of soot. Visibility is enhanced by the presence of moisture or impurities (such as sulfur) in the air. Hydrogen flames are readily visible in the dark or subdued light. A hydrogen fire can be indirectly visible by way of emanating “heat ripples” and thermal radiation, particularly from large fires. In many instances, flames from a hydrogen fire may ignite surrounding materials that do produce smoke and soot during combustion. Hydrogen flames are almost invisible in daylight. Corn brooms are sometimes used by emergency response personnel to detect hydrogen flames.

Hydrogen fires can only exist in the region of a leak where pure hydrogen mixes with air at sufficient concentrations. For turbulent leaks, air reaches the centerline of the leakage jet within about 5 diameters of a leakage hole, and the hydrogen is diluted to nearly the composition of air within roughly 500 to 1000 diameters. This rapid dilution implies that if the turbulent leak were into open air, the flammability zone would exist relatively close to the leak. Therefore, when the jet is ignited, the flame length is less than 500 diameters from the hole (for example, for a 1 mm diameter leak, the flame length will be less than 0.5 m).

In many respects, hydrogen fires are safer than gasoline fires. Hydrogen gas rises quickly due to its high buoyancy and diffusivity. Consequently hydrogen fires are vertical and highly localized. When a car hydrogen cylinder ruptures and is ignited, the fire burns away from the car and the interior typically does not get very hot. Gasoline forms a pool, spreads laterally, and the vapors form a lingering cloud, so that gasoline fires are broad and encompass a wide area. When a car gasoline tank ruptures and is ignited, the fire engulfs the car within a matter of seconds (not minutes) and causes the temperature of the entire vehicle to rise dramatically. In some instances, the high heat can cause flammable compounds to off-gas from the vehicle upholstery leading to a secondary explosion.

Hydrogen burns with greater vigor than gasoline, but for a shorter time. Pools of liquid hydrogen burn very rapidly at 3 to 6 cm/min compared to 0.3 to 1.2 cm/min for liquid methane, and 0.2 to 0.9 cm/min for gasoline pools. Hydrogen emits non-toxic combustion products when burned. Gasoline fires generate toxic smoke.

QUENCHING GAP

The quenching gap (or quenching distance) describes the flame extinguishing properties of a fuel when used in an internal combustion engine.Specifically, the quenching gap relates to the distance from the cylinder wall that the flame extinguishes due to heat losses.

The quenching gap has no specific relevance for use with fuel cells. The quenching gap of hydrogen (at 0.064 cm) is approximately 3 times less than that of other fuels, such as gasoline. Thus, hydrogen flames travel closer to the cylinder wall before they are extinguished making them more difficult to quench than gasoline flames. This smaller quenching distance can also increase the tendency for backfire since the flame from a hydrogen-air mixture can more readily get past a nearly closed intake valve than the flame from a hydrocarbon-air mixture.

Leave a comment