In spite of important optimisations for Hydrogen Storage in the last couple of years, containing Hydrogen remains a challenge. In order to be contained effectively and used as fuel, hydrogen needs to to be kept either as gas at atmospheric temperature under high pressure or as liquid at lower pressure but at cryogenic temperatures, or injected in a certain amount with natural gas other compounds (such as ammonia), otherwise at standard conditions it occupies a large container. Yet besides storage, hydrogen is difficult to transport too. While manufacturers of fuel cells and gas turbines are well on the way to solving the problems involved in turning hydrogen into energy, there are also numerous problems involved in delivering the hydrogen to these devices. Therefore the issue is: how to carry hydrogen to the refuelling stations to supply travelling cars or use it in general as fuel for various applications?

TRANSPORT OF HYDROGEN

Current Status = Currently, hydrogen is mostly used by the industrial sector, especially by chemical and petrochemical industries. For these applications, Hydrogen is mainly produced from natural gas by Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) process or from coal by gasification. At the moment, most of the hydrogen is produced and consumed at the same site, and only a small part of it is delivered to industrial plants via pipelines. For the part of hydrogen which is distributed between hydrogen production facilities and industrial units, the transport of compressed hydrogen via pipeline has been considered as the most cost-effective option for short distances (less than 3000 km) keeping the diameters of the hydrogen pipelines currently relatively small, at approximately 100-300 mm. That’s because for now there is little experience on long-distance transport, and building of dedicated pipelines is expensive.

At the status of the year 2023, there are approximately 5000 km of existing hydrogen pipelines in the world and from this around 50% (2475km) are in the USA. In Europe, there are approximately 15 operational dedicated hydrogen pipelines with a total length of 1500 km. Many of these existing hydrogen pipelines have operated successfully for decades, at pressures up to 100 bar.

In Europe, some hydrogen is also distributed at refueling station for hydrogen-powered vehicles. Germany for instance holds the leading position for distribution, with almost 100 stations, a number that is constantly rising; they are located along the motorway arteries, making it possible to travel within the country. In France – in Paris hydrogen is produced locally, allowing a taxi network to run efficiently with the aim of having half the fleet powered by hydrogen by 2024. In Italy there is just one station for cars on the Brenner motorway in Bolzano Sud. Here, hydrogen is locally sourced from the hydroelectric power produced by the rivers in mountains.

Challenges of hydrogen transport = In principle, the turbines at the heart of gas-fired power stations need relatively little modification to run on hydrogen instead of natural gas, so burning hydrogen can help keep your power grids from becoming dangerously imbalanced, especially over season-long timescales when might face weeks with little solar or wind power. However, despite ambitious plans and a few successful projects, hydrogen transport includes several factors that need to be addressed in order to secure safe operation, to meet end-users needs, and to maintain long lifetimes for both infrastructure and end-user applications. As the hydrogen economy is in its early phase and social acceptance plays a notable role in its development, there is no room for accidents or other major drawbacks.

The U.S. natural gas pipeline network is a highly integrated network of about 4,8million km that moves natural gas throughout the continental United States, in comparison with their currently available 2575km (primarily along the Gulf Coast) of hydrogen gas pipeline network. Likewise The EU has the most developed natural gas network in the world. It constitutes more than 200.000 km of transmission pipelines, over 2 million km of distribution networks, and more than 20.000 compressor and pressure reduction stations, in comparision with only 1500km of its hydrogen pipeline network. 40% of households in EU are connected to the natural gas network. In short, the EU natural gas network is capable of transporting and storing large quantities of energy and is well connected to the final consumers.

Hence, obviously there is already a huge pipeline network for natural gas. The main problem with hydrogen gas though consists in the fact that in order to be distributed, special pipelines are necessary, because those intended for methane and natural gas are not fully compatible with hydrogen, unless natural gas+hydrogen mixtures with a low hydrogen content are used. Building an entire network of hydrogen distributors globally for automotive transport involves considerable costs and delays. Replacing existing natural gas pipelines with new infrastructure that is safe for hydrogen would be very expensive too. So the most convenient would be to use what we already have. At the first glance, things seems to be convenient and simple enough to do. Yet,at an in-depth analysis it’s a big challenge. Here are the main obstacles:

- Hydrogen embrittlement;

- Pipeline Repurposing;

- Fatigue of pipelines

- Leak detections

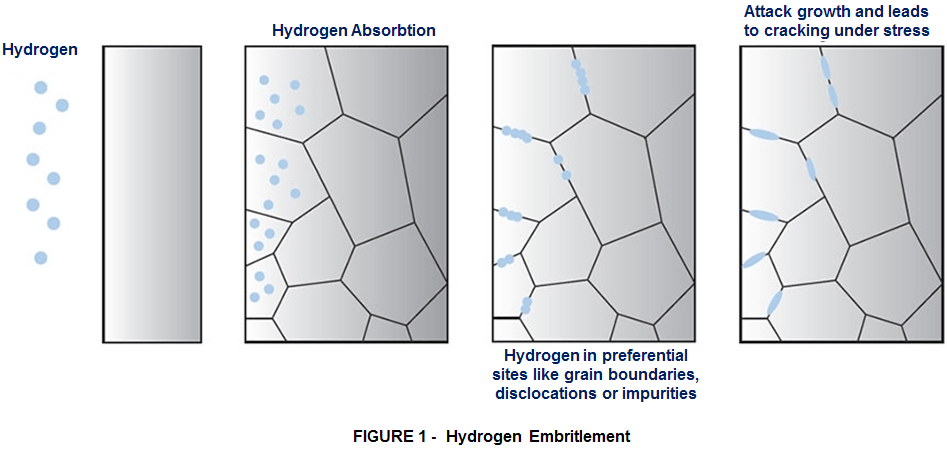

CHALLENGE 1 = Hydrogen embrittlement

About 96% of existing natural gas transmission pipelines in the US are steel. And Steel is susceptible to ”hydrogen embrittlement” which is the loss of strength of the metal due to hydrogen entering into tiny spaces in the metal, causing the pipe to crack. This makes nearly all of the current natural gas transmission pipelines in the US and Europe unsafe for transporting hydrogen in high volumes on long distances. Safe transportation of hydrogen requires either plastic pipelines with a coating to prevent hydrogen leakage or substantial modification of steel pipes. For the transportation purposes the hydrogen pipelines can be made from typical pipeline steel grades such as API 5L X42/X52, but the wall thicknesses are larger than in case of natural gas pipelines.Today, the plastic pipelines comprise a very small portion of the existing transmission pipeline system, and for distribution over half of pipelines are plastic. To enable the reassignment of the current natural gas pipeline network few measures have been suggested, such as coating, use of inhibitors (O2, CO or SO2) and pipe-in-pipe solutions.

The coating indeed provides some protection against hydrogen embrittlement, but the coating of existing pipelines is practically extremely challenging. The use of inhibitors can protect against permeation, but inhibitors may be toxic, cause safety risks, and increase purity requirements of hydrogen. And the pipe-in-pipe solution means adding hydrogen compatible pipe inside a pipeline, but this requires additional material and is challenging to implement in existing pipelines. All these ideas could work, but not on long distances.

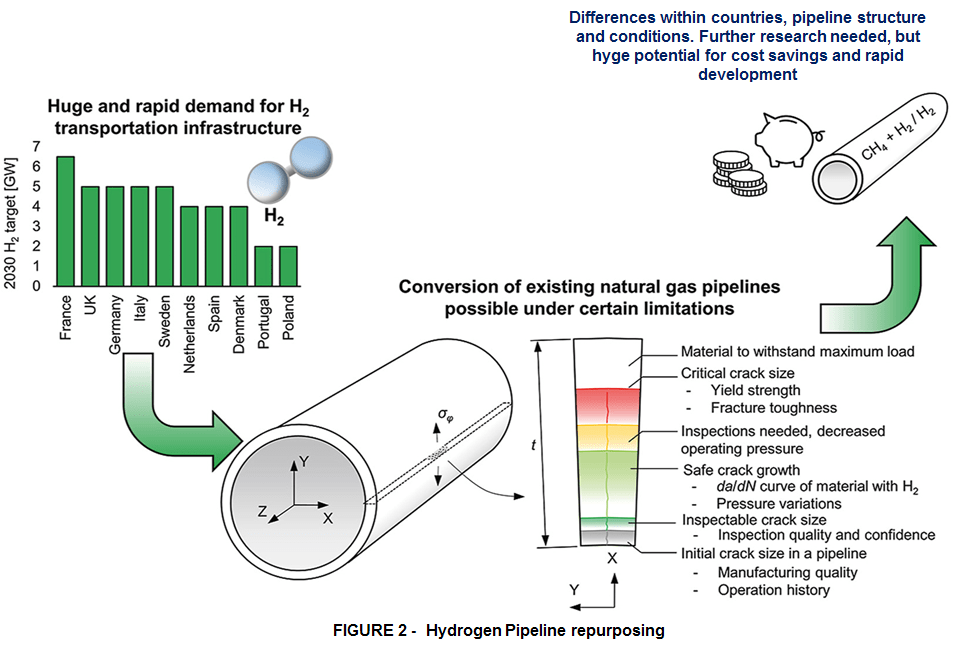

CHALLENGE 2 = Pipeline Repurposing

Repurposing of existing pipelines would require modifications to existing assets such as valves and seals. Since hydrogen is less dense than natural gas, adding hydrogen to gas requires larger total volumes to produce the same amount of energy. Earlier studies claim that approximately 70% of energy flow can be maintained when changing from natural gas to hydrogen. Also, gas flow metering devices, compressors, and end-user applications may need modifications. That’s because maintaining the energy flow for hydrogen requires a high compression power too. It has been estimated that compression power must be 3-fold to maintain the flow rate when changing from natural gas to hydrogen. Suitable compressors for hydrogen transport exists, but high diameters of natural gas pipelines can still cause challenges in case of repurposing.

Repurposing of existing pipelines is expected to result in significant savings compared to the building of new pipelines. Recent estimates show that cost of repurposed pipelines could be 0.2-0.6 million €/km whereas the building of new pipelines could cost 1.4-3.4 million €/km. Hence, several European countries are interested either in blending hydrogen to existing natural gas pipe-lines or repurposing the existing pipelines to transport 100% hydrogen. The blending of hydrogen into the natural gas pipelines as well as operation of dedicated hydrogen pipelines may require improved maintenance and inspection procedures. Researchers estimate that hydrogen can only comprise about 20% by volume or 7% of energy content, before it creates safety hazards in unmodified pipelines. Additional volume means additional compressor stations to move comparable amounts of energy through the pipeline system, resulting in a host of environmental justice, health, and climate issues.

Most of the implemented or ongoing projects inject only small amount of hydrogen into the natural gas grid (≤2 vol-%), but some projects have reached high blending rates (up to 20vol-%), e.g., the Ameland in the Netherlands, the GRHYD in France, and the HyDeploy in the UK. These projects did not utilize steel pipelines but plastic, copper, brass, and even rubber pipelines. The results of the HyDeploy project suggest that up to 20 vol-% hydrogen can be safely injected into the grid and hydrogen does not have effects on applications such as boilers, meters, or cookers.

Some gas users do not tolerate hydrogen and some of them require pure hydrogen, and thus gases need to be separated. Deblending is technically possible, e.g., using the pressure swing absorption process. The process currently consumes approximately 8-15 kWh/kgH2 and costs around 5-7 €/kgH2. Researches claims that deblending route could be economically feasible only if hydrogen is recovered at low pressure. Moreover, as some end-user applications such as fuel cells require very pure hydrogen, compounds such as sulfur residues in natural gas pipeline could cause problems if an existing pipeline is converted for 100% hydrogen .

CHALLENGE 3 = Fatigue of pipelines

Fatigue of pipelines can be expressed as crack propagation which is caused by pressure fluctuations during the service life of the pipeline. The use of gas and the operation of pipeline compressors are the main reasons for the pressure variation. In case of natural gas pipelines, the fatigue of structures does not typically become a concern as the material strength limits maximum operation pressure. High strength steels (e.g. X100) enables a balance between high constant operating pressure and fatigue life. Yet, In case of hydrogen gas pipelines, this might be a serious concern because steel if not protected, is highly susceptible to “hydrogen embrittlement”. Increased pressure variation potential with high-performance pipelines highlights the fatigue performance which becomes more important aspect in design and through service life in the natural gas transmission lines.

CHALLENGE 4 = Leak detections

Diatomic Hydrogen (H2) is a small and reactive molecule. It tends to leak from small crack, seals, and joints of pipelines. Current leak detection systems are designed for gas, not for hydrogen, and would have to be upgraded to detect hydrogen, a colorless, tasteless, odorless gas. The alternative would be to carry hydrogen in liquid state, like oil derivatives, but the liquid state of hydrogen is reached at a temperature of -253°C, with heavy energy expenditure to transform it and then keep it in the liquid form, hence not very convenient idea. Thus, leakage detection is important for safety, but existing methods may cause challenges. Some earlier studies claim that there are no suitable odorants for hydrogen.Existing odorants are not light enough to travel with hydrogen, and especially sulfur containing odorants are harmful to fuel cells and storages. Therefore, current hydrogen pipelines mostly use detectors instead of odorants. Odorization may be easier with mixtures of natural gas and hydrogen than with 100% hydrogen.

Leave a comment