On Earth Hydrogen elemental Hydrogen is scarce. It is difficult to get and diffcult to handle. However there are plenty of sources easily available on our planet from where we can get Hydrogen. There a lot of it combined in molecules with other elements such as Oxygen (in water) and Carbon (in hydrocarbons) plus various organic compounds. While there have been some intriguing recent discoveries of natural hydrogen sources, these are unlikely ever to meet more than a minuscule fraction of demand. You can keep prospecting for natural hydrogen, but don’t expect too much. To use hydrogen for our energy needs, such as in fuel cells and for combustion in engines as alternative to fossil fuels, we must separate hydrogen from its compounds. So far, we have developed tools to wield hydrogen’s stored energy in variety of ways, making it a remarkably versatile fuel. Now you have chosen a clean way to make your hydrogen and in order to take the most of it, you also must be able to store and carry it in a convenient form. And the problem is exactly this, how might you conveniently store hydrogen?

Wel, indeed hydrogen storage remains a challenge. To understand why, first let’s take a look at how hydrogen behaves when contained. Two characteristics are important here:

- The Expansion Ratio of Hydrogen

- The Hydrogen Leakage

THE EXPANSION RATIO OF HYDROGEN

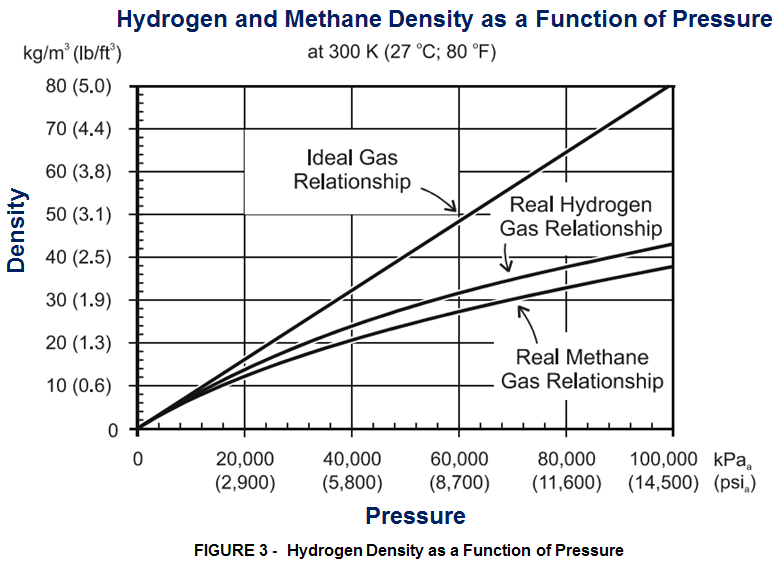

Elemental Hydrogen is not easy to store. That’s because Hydrogen gas is less dense than Natural gas (mostly made of methane CH4), which makes it particularly hard to store, i.e. it occupy more volume and hence requires a large fuel tank for storage. In liquid state, of course Hydrogen occupies less storage space than in gaseous state, but it does not burn. To make it burn you must heat it to become a gas, but then you’ll need a larger container. So in order to find the dimension for a proper storage container you must know the difference in volume. This difference in volume between liquid and gaseous hydrogen can easily be appreciated by considering its expansion ratio.

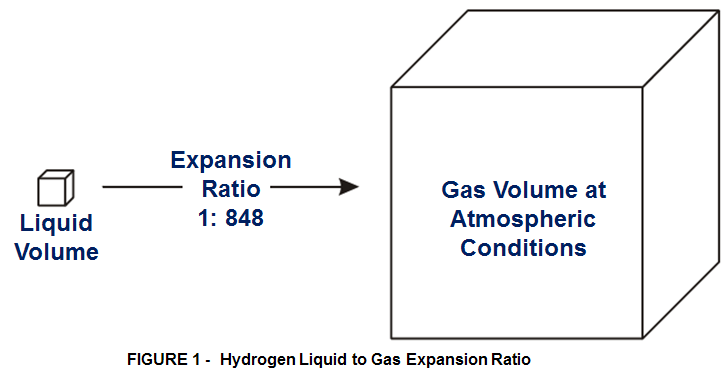

EXPANSION RATIO is the ratio of the volume at certain temperature and pressure at which a gas or liquid is stored compared to the volume of the gas or liquid at atmospheric pressure (1atm) and temperature (0°C).

When hydrogen is stored as a liquid, (in cryogenic condition at -240°C° and at 10-12 bars) , it vaporizes upon expansion to atmospheric conditions with a corresponding increase in volume. Hydrogen’s expansion ratio of 1:848 means that hydrogen in its gaseous state at atmospheric conditions occupies 848 times more volume than it does in its liquid state.

Likewise, when hydrogen is stored as a high-pressure gas at 3600 psi (250 bar) and atmospheric temperature, its expansion ratio to atmospheric pressure is 1:240. While a higher storage pressure increases the expansion ratio somewhat, gaseous hydrogen under any conditions cannot approach the expansion ratio of liquid hydrogen.

HYDROGEN LEAKAGE

The molecules of hydrogen gas are smaller than all other gases, and it can diffuse through many materials considered airtight or impermeable to other gases. This property makes hydrogen more difficult to contain than other gases. Leaks of liquid hydrogen evaporate very quickly since the boiling point of liquid hydrogen is so extremely low ( -253°C). Hydrogen leaks are dangerous in that they pose a risk of fire where they mix with air. However, the small molecule size that increases the likelihood of a leak also results in very high buoyancy and diffusivity, so leaked hydrogen rises and becomes diluted quickly, especially outdoors. This results in a very localized region of flammability that disperses quickly. As the hydrogen dilutes with distance from the leakage site, the buoyancy declines and the tendency for the hydrogen to continue to rise decreases. Very cold hydrogen, resulting from a liquid hydrogen leak, becomes buoyant soon after it evaporates.

In contrast, leaking gasoline or diesel spreads laterally and evaporates slowly resulting in a widespread, lingering fire hazard. Propane gas (C3H8) for instance is denser than air so it accumulates in low spots and disperses slowly, resulting in a protracted fire or explosion hazard. Heavy vapors can also form vapor clouds or plumes that travel as they are pushed by breezes. Another example is Methane gas (CH4) which is lighter than air, but not nearly as buoyant as hydrogen, so it disperses rapidly, but not as rapidly as hydrogen.

For small hydrogen leaks, buoyancy and diffusion effects in air are often overshadowed by the presence of air currents from a slight ambient wind, very slow vehicle motion or the radiator fan. In general, these currents serve to disperse leaked hydrogen even more quickly with a further reduction of any associated fire hazard. When used as vehicle fuel, the propensity for hydrogen to leak necessitates special care in the design of the fuel system to ensure that any leaks can disperse with minimum hindrance and the use of dedicated leak detection equipment on the vehicle and within the maintenance facility. However, Hydrogen leaks pose a potential fire hazard, especially in closed areas.

===================================================================

With these 2 characteristics as just described, now let’s see how we can store Hydrogen.

HYDROGEN STORAGE

As mentioned earlier hydrogen needs space. So a tank of hydrogen gas is quite large compared to a tank of petrol or natural gas.

The boiling point of a fuel is a critical parameter since it defines the temperature to which it must be cooled in order to store and use it as a liquid. Liquid fuels take up less storage space than gaseous fuels, and are generally easier to transport and handle. For this reason, fuels that are liquid at standard atmospheric conditions (such as gasoline, diesel, methanol and ethanol) are particularly convenient. Conversely, fuels that are gases at atmospheric conditions (such as hydrogen and natural gas) are less convenient as they must be stored as a pressurized gas or as a cryogenic liquid. The boiling point of a pure substance increases with applied pressure—up to a point. For instance, Propane (C3H8), with a boiling point of –42 ºC, can be stored as a liquid under moderate pressure, although normally it is a gas at atmospheric pressure. (At temperatures of 21 ºC a minimum pressure of 7.7 bar is required for liquefaction of propane). Unfortunately, hydrogen’s boiling point can only be increased to a maximum of –240 ºC through the application of approximately 13 bar, beyond which additional pressure has no beneficial effect. So Hydrogen as a vehicle fuel can be stored either as a high pressure gas or as a cryogenic liquid, which in both cases at the current status of technology available is a costly process.

Even in liquid form, hydrogen takes up a lot of space. Also, because molecules of hydrogen (element number one on the periodic table) are even tinier than other molecules, you need extremely tight seals to prevent leaks — and you really want to prevent leaks, because hydrogen, like gasoline and natural gas, is both valuable and highly flammable. Pouring petrol into a tank is quick and easy, just as it is hooking up the cable to recharge the battery of an electric car. Hydrogen, on the other hand, is a difficult gas to handle because, having a low volumetric energy density, it has to be highly compressed at high pressures (from 350 to 700 bar at ambient temperature) to be packed into a tank in sufficient quantities to power a car.

5 or 6 kg of hydrogen are required to cover about 600 km. In a car’s tank, if it were not compressed, there would be enough hydrogen to cover just 5 km.

So how can we do it better for hydrogen storage?

Improvement ideas for hydrogen storage potential already exist and further development still needs to be done. But at least 2 such ideas are worth to be mentioned.

IDEA 1 = Some projects propose converting hydrogen to liquid ammonia (NH3) for storage and transportation, then converting the ammonia back to hydrogen at the site of power generation. The energy for this process is about equal to that of cooling and liquefying hydrogen, and far more infrastructure exist for safely handling, transporting, and storing ammonia than elemental hydrogen. Safe handling of hydrogen is somehow already a routine in heavy-industrial environments and combining hydrogen with nitrogen to store it as ammonia is also a good solution for some applications. Nevertheless, it will be difficult to solve the problems of hydrogen handling over the range of applications required for a full-fledged hydrogen economy. Large-scale real-world experimentation, deployment, gathering of experience, and drawing of lessons is needed.

IDEA 2 = The amount of energy produced from renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power tends to fluctuate because of weather conditions. Combining energy storage solutions with renewables mitigates the intermittent nature of renewable energy production, and hydrogen is a proven provider of effective storage. Converting renewable energy to hydrogen via electrolysis allows it to be stored and used at a later date, while also stabilizing the energy grid by providing a source of energy “on tap”. Better still, the hydrogen can be stored for long periods without significant losses.

=====================================================

Leave a comment