Hydrogen is the simplest, lightest and smallest possible atom in existence; it has only 1 electron and a nucleus of 1 proton. You can visualize a hydrogen atom as a dense central nucleus with a single orbiting electron, much like a single planet in orbit around the sun. Scientists prefer to describe the electron as occupying a “probability cloud” that surrounds the nucleus somewhat like a fuzzy, spherical shell (as shown in Fig 1).

Although as element, it is rare on Earth, hydrogen is the most common element in the Universe. It is the main constituent of stars, including The Sun and giant gaseous planets such as Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune and Uranus. Basically the Sun is 4-fifth Hydrogen. At the centre of a star atoms of this element are fused together, releasing heat and light. New stars form inside nebulae – such as the Orion Nebula – all because of Hydrogen. Therefore Hydrogen is litterally “THE FUEL OF THE UNIVERSE”. Hence, let’s take a closer look at what is Hydrogen able to do.

THE PROPERTIES OF HYDROGEN

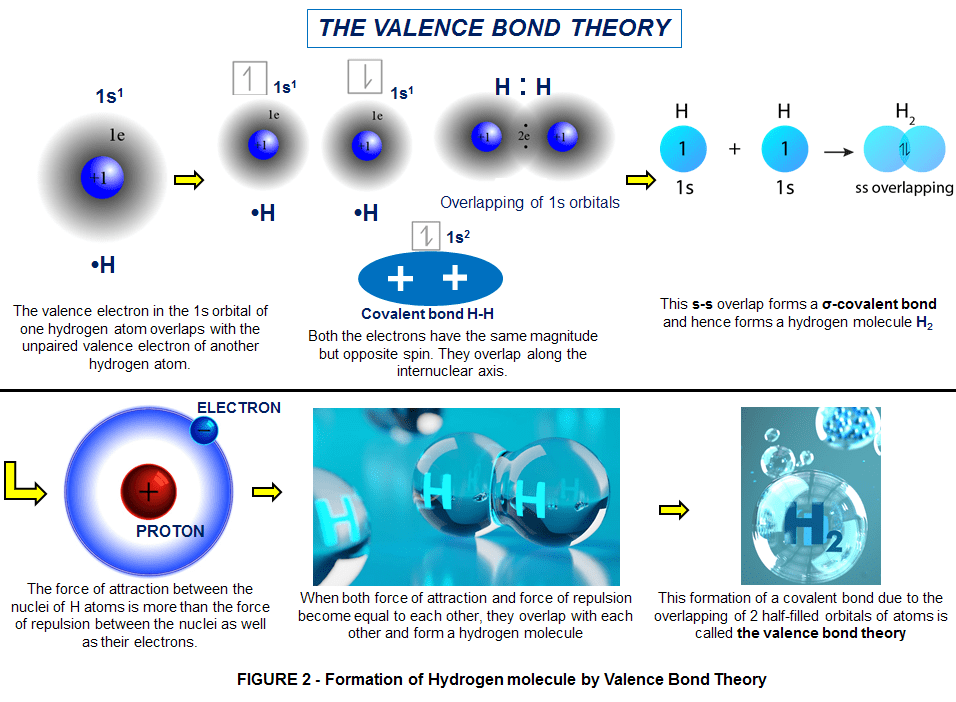

Chemically, the atomic arrangement of a single electron orbiting a nucleus is highly reactive. Yet, this is totally depended on temperature. At normal temperature hydrogen is a not very reactive substance, unless it has been activated somehow; for instance, by an appropriate catalyser. Instead at high temperatures it’s highly reactive. For this reason, hydrogen atoms naturally combine into molecular pairs also called diatomic molecule (as H2 instead of H). This behaviour is known as “The Valence Bond Theory” (as shown in Figure 2).

So a molecule of hydrogen is the simplest possible molecule. It consists of 2 protons and 2 electrons held together by electrostatic forces. Like atomic hydrogen, the assemblage can exist in a number of energy levels. To further complicate things, each proton in a hydrogen pair has a field associated with it that can be visualized and described mathematically as a “spin”.

Molecules in which both protons have the same spin are known as “orthohydrogen”.

Molecules in which the protons have opposite spins are known as “parahydrogen”.

Over 75% of normal hydrogen at room temperature is ortho-hydrogen. This difference becomes important at very low temperatures since ortho-hydrogen becomes unstable and changes to the more stable para-hydrogen arrangement, releasing heat in the process. This heat can complicate low temperature hydrogen processes, particularly liquefaction.

Although hydrogen is officially placed at the top of Group 1A in most versions of the Periodic Table, it is very different from the other members of the group 1A ( a.k.a alkali metal group), therefore is usually considered a category by itself. On Earth, at standard temperature (0°C) and pressure (1 atm) the element hydrogen is a gas. But still Hydrogen is often included in the category of “non-metals” and not in the category of “gases”. This is because in the face of extreme pressures (about 2 million atmospheres) and extremely low temperatures (close to zero Kelvin) hydrogen becomes a solid and behaves like a light-metal capable of conducting electricity. It has been theorized that center of the giant planets such as Jupiter consists of metallic hydrogen.

The group 1A of the Periodic Table include the alkali metals: Lithium (Li), Sodium (Na), Potassium (K), Rubidium (Rb), Cesium (Cs), and Francium (Fr). The reason why H is more often associated with the elements in the group 1A is also because the single electron in the H atom occupies an s orbital around its nucleus, as do the outermost layer of electrons in the atoms of the other elements in group 1A. And like them, the hydrogen atom easily lose its electron becoming a positively charged ion (a.k.a. cation) H+. However, all these elements in group 1A at standard temperature and pressure are solid metals, while as mentioned Hydorgen is gas.

However in order to complete its layer a H atom can also accept an electron becoming a negatively charged ion (anion)(H–) in the same way as elements in group 7A do. So on some periodic tables, in fact, hydrogen is placed at the top of Group 7A, since like the halogens, it can form a -1 charge. The Group 7 A includes: Flourine (F), Chloride (Cl), Bromine (Br), Iodine (I), Astatine (At) and Tennessine (Ts).

==========================================

Exaclty because of its atomic simplicity, hydrogen is so light, that the pure element isn’t commonly found naturally on Earth. It would just float away and can easily escape the Earth atmosphere.The prime components of air, nitrogen (N) and oxygen (O), are 14 and respectivelly 16 times heavier, giving hydrogen dramatic buoyancy. Hydrogen rises at almost 20 m/s and disperses rapidly. This buoyancy is a built-in safety advantage in an outside environment. Because its molecular weight is lower than that of any other gas, its molecules have a velocity higher than those of any other gas at a given temperature and it diffuses faster than any other gas. Consequently, kinetic energy is distributed faster through hydrogen than through any other gas; it has, for example, the greatest local heat conductivity.

ODOR, COLOR and TASTE = Pure hydrogen is odorless, colorless and tasteless. A stream of hydrogen from a leak is almost invisible in daylight. Compounds such as mercaptans and thiophanes that are used to scent natural gas may not be added to hydrogen for fuel cell use as they contain sulfur (S) that would poison the fuel cells.Thus Hydrogen cannot be odorized. Hydrogen that derives from reforming other fossil fuels is typically accompanied by nitrogen (N2), carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO) and other trace gases. In general, all of these gases are also odorless, colorless and tasteless. Hydrogen is transparent to visible light, to infrared light, and to ultraviolet light to wavelengths below 1800 Å.

FLAMABILITY = Hydrogen gas is highly flammable. It easily mixes with oxygen whenever air is allowed to enter a hydrogen vessel, or when hydrogen leaks from any vessel into the air. Hydrogen is the most flammable all the known substances. It is flammable and explosive over a wide range of concentrations (from 4% LFL to 75% UFL presence in air), so it should be safely stored and used in an area that is free of heat, flames, and sparks. It has an auto-Ignition temperature of 585°C.

Once heated at its auto-ignition temperature, hydrogen can be ignited even by the tiny spark such as the electostatic discharge between 2 persons. Its ignition sources actually take any form of spark, flame, or high heat. Pure hydrogen fires flame burns with a pale blue flame and is difficult to detect; it is almost invisible to the eye during the day. A pure hydrogen fire gives up almost no radiant heat and no smoke.

BOILING AND MELTING POINTS = Hydrogen has the second lowest boiling point and melting points of all substances, second only to helium (He). Molecular hydrogen (H2) boils at -253°C (20 K). Below this point is in liquid state, thus making it cryogenic. Hydrogen does not burn in liquid state, however it will revert to a gas upon warming an can then be ignited. It has a melting point at -259°C (14K) and below this point at atmospheric pressure hydrogen is a solid. Obviously, these temperatures are extremely low. Temperatures below -73 ºC (200 K) are collectively known as cryogenic temperatures, and liquids at these temperatures are known as cryogenic liquids.

To give you a perpective, based on measurements of cosmic microwave background radiation, the average temperature of the universe today is approximately 2.73 kelvins (−270.42 °C),while the temperature of 0 (zero) K is the lowest possible temperature that matter can have. For this reason it’s very difficult to get solid hydrogen on Earth. Research on this topic continues, we might not get exatly 0 °K but we might come very close to it. Actually in early 2019, this information has been confirmed at least twice as metallic hydrogen was made in the laboratory. Moreover, a 250K Meissner effect has been observed, which means hydrogen at extremmelly low temperatures is a veritable superconductor. We already can make Hydrogen in liquid state which is also an extremelly cold substance, so one day we could indeed maintain that low level of temperature needed and hence make solid hydrogen easier too. Or perhaps we can play with pressure so that superconducting solid hydrogen can occur at higher temperatures.

DENSITY = Density is measured as the amount of mass contained per unit volume. Density values only have meaning at a specified temperature and pressure since both of these parameters affect the compactness of the molecular arrangement, especially in a gas. The density of a gas is called its vapor density, and the density of a liquid is called its liquid density. Hydrogen has lowest atomic weight of any substance and therefore has very low density both as a gas and a liquid. Its relative density at Normal Pressure and Temperature (at 20°C and 1 atm), compared with that of the air, is 0.0695 g/cm3.

SPECIFIC VOLUME = Specific volume is the inverse of density and expresses the amount of volume per unit mass. Thus at 20°C and 1 atm, the speific volume of hydrogen gas is 11.9 m3/kg and for liquid hydrogen the specific volume at -253°C and 1 atm is 0.014m3/kg

SPECIFIC GRAVITY = Specific gravity is the ratio of the density of one substance to that of a reference substance, both at the same temperature and pressure. It expresses the relative density. For vapors, air (with a density of 1.203 kg/m3) is used as the reference substance and therefore has a specific gravity of 1.0 relative to itself. The density of other vapors are then expressed as a number greater or less than 1.0 in proportion to its density relative to air. Gases with a specific gravity greater than 1.0 are heavier than air; those with a specific gravity less than 1.0 are lighter than air. Gaseous hydrogen, with a density of 0.08375km/m3, has a specific gravity of 0.0696 and is thus approximately 7% the density of air.

For liquids, water (with a density of 1000 kg/m3) is used as the reference substance, so has a specific gravity of 1.0 relative to itself. As with gases, liquids with a specific gravity greater than 1.0 are heavier than water; those with a specific gravity less than 1.0 are lighter than water. Liquid hydrogen, with a density of 70.85 g/L, has a specific gravity of 0.0708 and is thus approximately (and coincidentally) 7% the density of water.

THERMAL CONDUCTIVITY = this is a physical property which gives us an idea about a material’s capability to conduct heat. Its higher values describe better heat conduction. For most gases and vapors, the value of thermal conductivity is between 0.01 and 0.03 W/mK at room temperature. However, hydrogen is an exception. It has the highest thermal conductivity of any gas (0.18 W/mK). The only one close is helium (0.15W/mK). The reason behind such high thermal conductivity of hydrogen is because two isomers of hydrogen exist – ortho and para hydrogen. They stay in equilibrium with each other. The thermal conductivity of hydrogen depends on temperature and pressure. At standard temperature and pressure, hydrogen gas has around 25% of the para form and 75% of the ortho form. Whereas at very low temperatures, the para form is more exclusively present. In the contrast, with the increase in temperature, the ortho fraction increases. However, Hydrogen is still regarded as a poor conductor of heat. The reason for this comes from the principle of conduction which states that the electrons must move freely for conduction to take place. But becasue Hydrogen has only 1 electron, it holds it tighly, it cannot move freely, so as consequence at normal temperature, hydrogen conducts heat and electricity poorly.

ELECTRICAL CONDUCTVITY = Similar to thermal conductivity, the electrical conductivity of hydrogen depends on temperature. If hydrogen is cooled enough, it can be a superconductor. It can also be heated to a high temperature to make it exist as a plasma, which is highly conductive. If the pressure is high enough, hydrogen becomes a good conductor as well. Liquid metallic hydrogen (LMH) for instance is the most abundant form of condensed matter in our solar planetary structure. Under a pressure region of 1.4-1,7 Mbar based on spectrally resolved measurements of the optical reflectance of LMH, it was determined that the LM Hydrogen’s static electrical conductivity to be in a range of 11.000 – 15.000 S/cm (Siemens/centimeter). Similar gases such as oxygen, nitrogen, etc. are all poor conductors of heat and electricity regardless of the applied pressure. However, hydrogen becomes a very good conductor of electricity at very high pressure. Experiments have shown that if the pressure is above 220 GPa, hydrogen becomes opaque and electrically 100% conductive. At 260–270 GPa, hydrogen will transform into a metal. As a result, the conductance of hydrogen will increase sharply. Upon changing the pressure up to 300 GPa or cooling to at least 30 K, the sample will reflect light well. But under normal condition of temperature (20°C) and pressure (1atm), hydrogen it is a poor conductor of electricity. Hydrogen in its natural state is a perfect insulator.

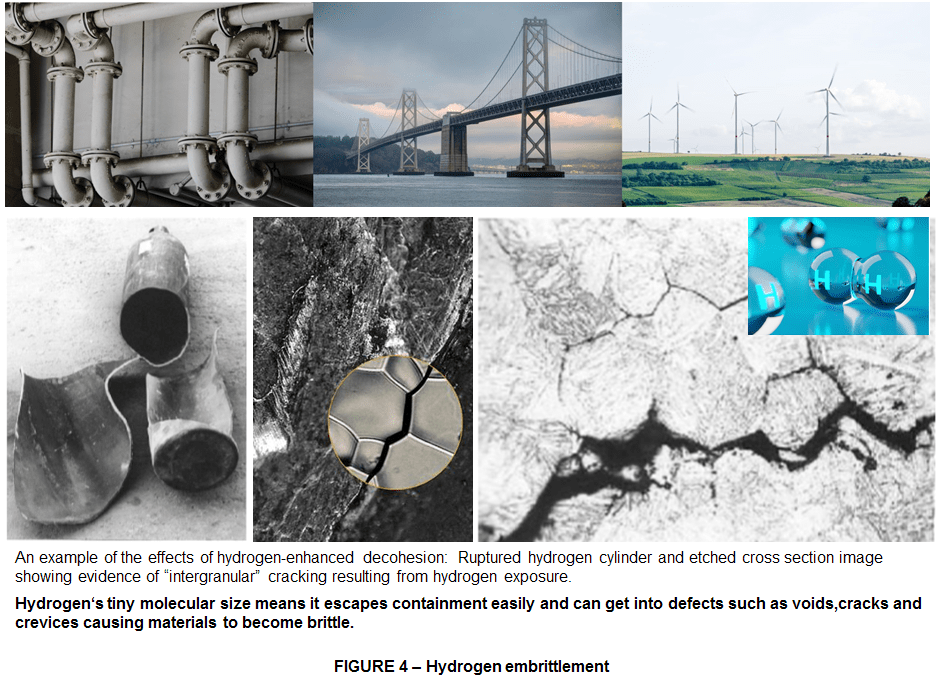

HYDROGEN EMBRITTLEMENT = Hydrogen is non-corrosive, but it can embrittle some metals (i.e., cause significant deterioration of the metal’s mechanical properties through the acceleration of the formation of fatigue cracks) so it is important that any material in contact with hydrogen be specifically chosen for compatibility. Hydrogen embrittlement can lead to leakage or catastrophic failures in metal and non-metallic components.The mechanisms that cause hydrogen embrittlement effects are not well defined. Factors known to influence the rate and severity of hydrogen embrittlement include:

- hydrogen concentration,

- hydrogen pressure;

- temperature;

- hydrogen purity;

- type of impurity;

- stress level;

- stress rate;

- metal composition;

- metal tensile strength;

- grain size in microstructure;

- heat treatment history

- moisture content.

TOXICITY = Hydrogen is non-toxic, is non-poisonous but high concentrations of this gas can cause an oxygen-deficient environment, hence displacing oxygen in the air and causing asphyxiation. Oxygen levels below 19.5% are biologically inactive for humans. Effects of oxygen deficiency may include:

- rapid breathing,

- headaches;

- diminished mental alertness,

- impaired muscular coordination,

- faulty judgement,

- depression of all sensations,

- emotional instability

- fatigue.

And asphyxiation progresses:

- dizziness,

- nausea,

- vomiting,

- the skin of a victim may have a blue color

- prostration loss of consciousness may result, eventually leading to convulsions, coma and under some circumstances, death may occur.

At concentrations below 12% O2, immediate unconsciousness may occur with no prior warning symptoms. In an enclosed area, small leaks of hydrogen pose little danger of asphyxiation whereas large leaks can be a serious problem since the hydrogen diffuses quickly to fill the volume. The potential for asphyxiation in unconfined areas is almost negligible due to the high buoyancy and diffusivity of hydrogen. Inhaled hydrogen can result in a flammable mixture within the body. Hydrogen is not expected to cause mutagenicity, embryotoxicity, teratogenicity or reproductive toxicity. Yet, pre-existing respiratory conditions may be aggravated by overexposure to hydrogen. On loss of containment, a harmful concentration of this gas in the air will be reached very quickly.

An overview of hydrogen main properties is presented in Figure 5

HEALTH EFFECTS OF EXPOSURE TO HYDROGEN = the biggest effect of human exposure to hydrogen is FIRE. As mentioned earlier hydrogen is extremelly flammable so you absolutelly must handle hydrogen very carefully. Heating hydrogen may cause violent combustion or explosion, because hydrogen reacts violently with air, oxygen, halogens and strong oxidants, causing fire and explozion hazard. Metal catalysts such as Platinum (Pt) and Nickel (Ni) greatly enhance these reactions.

Safety and first aid: In case you must work in an environment subjected to a high content of hydrogen, the first thing to do is to check the oxygen content before entering the area, as there is no odor warning if toxic concentration of hydrogen are present. Then measure the hydrogen concetrations with suitable gas detector (a normal flammable gas detector is not suited for this purpose).

As first aid, to remove the risk of total fire hazard, immediatelly shut off the fire supply. If fire is already there and it’s not possible to shut off and it’s no risk to surroundings, then let the fire burn itself out. In other cases extinguish it with water spray, powder & carbon dioxide (CO2). To remove the risk of explosion, in case of fire: keep the hydrogen cylinder cool by spraying with water and combat fire from a sheltered position.

In case of inhalation, leave the area immediatelly and take a breath in fresh air. If big amount of hydrogen is already inhaled, artificial respiration may be needed, refer to medical attention immediatelly.

ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS OF HYDROGEN: If fire doesn’t occur and there is a hydrogen leak in a working area, unless heat is also not applied, hydrogen is not dangerous. The gas will be dissipated rapidly in well-ventilated areas. Any effect on animals would be related to oxygen deficient environments, No adverse effect is anticipated to occur to plant life, except for frost produced in the presence of rapidly expanding gases. Regarding the aquatic life there is no evidence currently available on a negative effect of hydrogen on aquatic life.

Leave a comment