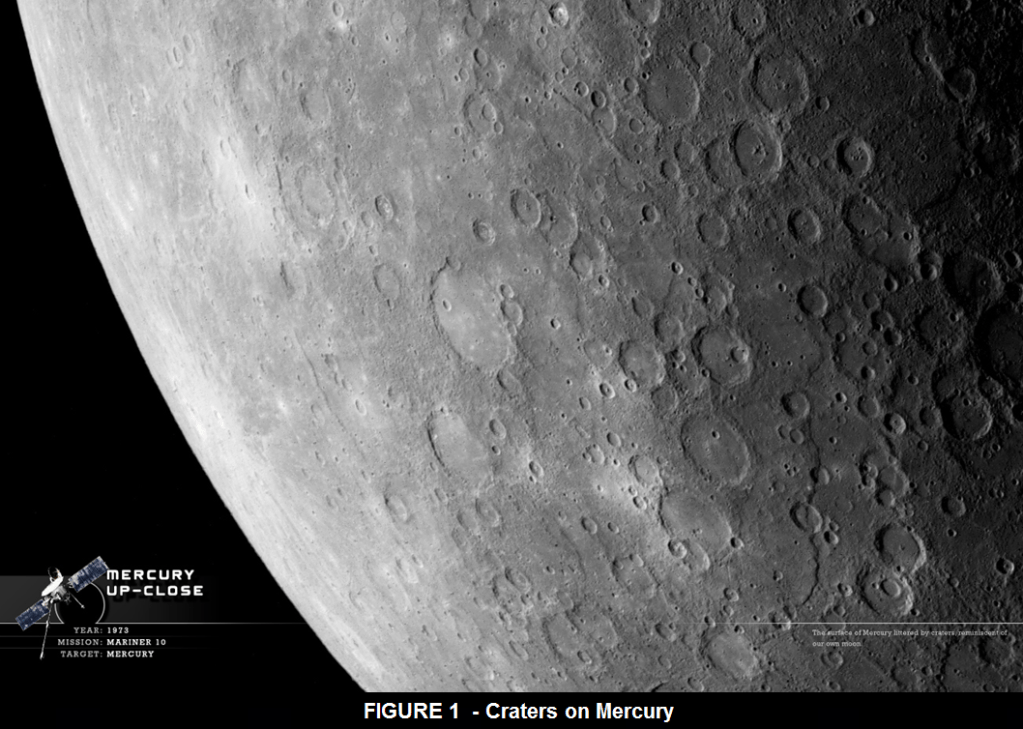

Mercury is one of the 4 terrestrial planet in our Solar System and also the one we didn’t know much about until quite recently. As it is the smallest planet among the total of 8 and also being the closest to the Sun, Mercury was dificult to study. In early research, astronomers believed that Mercury had a smooth surface. However, in November 1973, the Mariner 10 spacecraft flew past Mercury and soon revealed the planet’s pitted and smashed surface. It is a planet only slightly larger than the Earth’s moon with a diameter of about 4,880 km, which is slightly larger than the width of the United States. Being too small to hold on to an atmosphere that might protect it from meteorites and lacking any processes to recycle old terrain, this large amount of craters on its surface has given Mercury the title of ”The Most Cratered Planet” in our Solar System. In this article let’s explore the Mercury surface.

SURFACE FEATURES

In most publications about the planet, you find written that Mercury resembles the Moon and you might think that looking at the Moon through a telescope is like seeing Mercury. Also if we were to observe the Mercurian landscape from a well-isolated landing module – either directly, like a brave astronaut, or with a camera operated from a distance – the description of the view would resemble those transmitted to us by the astronauts of the Apollo missions. Yet in reality is not really like that.

Mercury up close: As bleak and bare as Earth’s moon, Mercury is covered by a mix of greyish-brown dust, white and dark-grey and bears the scars of countless meteorite impacts, from tiny pockmarks to vast multi-ringed basins, while the Moon is nearly on its entire surface covered by a rubble pile of charcoal-gray, powdery dust, and rocky debris called the lunar regolith. The dark-grey color on mercurian surface is coming from the rocks covered with mercurian regolith and the white belongs to the excavated rocks from the underground by meteorite impacts known as the Late Heavy Bombardment, which came early in the planet’s history, punching out most of the largest craters before quietening some 3.8 billion years ago. Soon afterwards lava flows spread across the surface to create smooth plains that obliterated some craters.

Later, the planet’s interior cooled and shrank, breaking the crust into cracks and ridges. Eventually about 750 million years ago, Mercury’s mantle shrank so much that lava ceased to flow out. Since then, the planet’s surface has hardly changed, it is stable and with no moving plates, meaning that features such as impact craters remain undisturbed on the planet for billions of years, though it continues to be scarred by minor impacts.

So if you like craters, then Mercury is surely the planet for you. Mercury has almost no atmosphere for protection therefore is continuously exposed to the battering of even small meteorites. There is also a distinct lack of volcanic activity and weather in the form of wind, clouds, storms, etc. so erosion is basically non-existent. For craters, this is good news, as they won’t be eroded away over time. Unlike other planets, these numerous craters form because Mercury does not “heal itself,” for want of a better term, after a collision. While most craters on Mercury are small, even of few centimeters, a few may be more than 80 km wide. Yet large meteorite impacts have produced multi-ring basins. The largest crater on Mercury being the basin called Caloris Planitia, with a diameter of 1,545km. This as large as the so-called “maria” on the moon – those round gray patches that we can see on the moon when we look with binoculars and even with the naked eye.

CALORIS PLANITIA BASIN – Like the large craters on the moon, Caloris Planitia on Mercury has a flat bottom, covered by lava fields and is surrounded by a mountainous ring up to 2000 meters high whose peaks create a 1,000 kilometre boundary around the lava plains within. On the other side of the mountains, the vast amount of material that was lifted from the planet’s surface at the moment of impact formed a series of concentric rings around the basin, stretching over 1,000 kilometres from its edge. This basin is located on the equator of Mercury, where the Sun shines the strongest, being the hottest region of the planet.

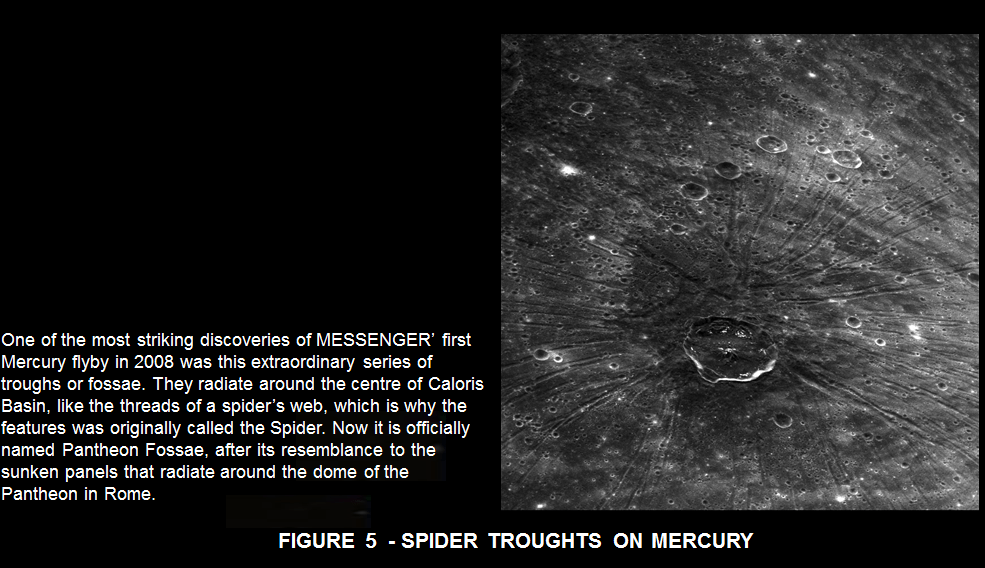

Caloris Plantia comes from Latin and it means “heat field”. It was formed when Mercury collided with a very large asteroid, with a diameter of about 100 km – It probably had a diameter about 10 times larger than the asteroid that caused the extinction of the dinosaurs on Earth. The impact caused seismic waves that shook the entire planet, and the “Mercurian earthquakes” that followed dislodged and moved the rocks from the diametrically opposite area of the planet. The extensive mountainous and hilly region that was thus created at the antipode of Caloris Planitia is called “weird terrain”. The shock waves crossed the planet and collided on the opposite side of Mercury, filling the planet with a seismic noise, so that for several hours or days it rang like a bell. The energy generated by the asteroid crash cracked the surface of Mercury, releasing the lava from the interior. The impact triggered an intense volcanic activity, which flooded rough surfaces, turning into smooth lava fields – in contrast to the so-called weird terrain, which is hilly and rugged. The craters are interspersed by at least two generations of flat plains of solidified basaltic lava, just like the lunar maria. Fluid lava oozed gently out of vents in the crust and pooled in depressions. Eventually, most of the vents were covered by the lava. The impact also shook the mountains on Mercury, causing landslides on their slopes.Debris and shock waves from the Caloris impact shot to the opposite side of Mercury, buckling the crust.

Impact shock waves : A few minutes after the formation of the Caloris Basin, the shock waves generated by the impact came to a focus on the opposite side of the planet. This caused a massive upheaval over an area of 250.000 square kilometres, raising ridges up to 1.8km high and 5-10km across. Crater rims were broken into small hills and depressions. As the surface gravity on Mercury is about twice that of the Moon, the ejecta blankets are closer to the parent craters and thicker than those found on the Moon. The collision that produced Caloris Planitia had terrible consequences, observable throughout the planet. The asteroid shook Mercury to its core, and if it had been much stronger it could have completely destroyed the planet.

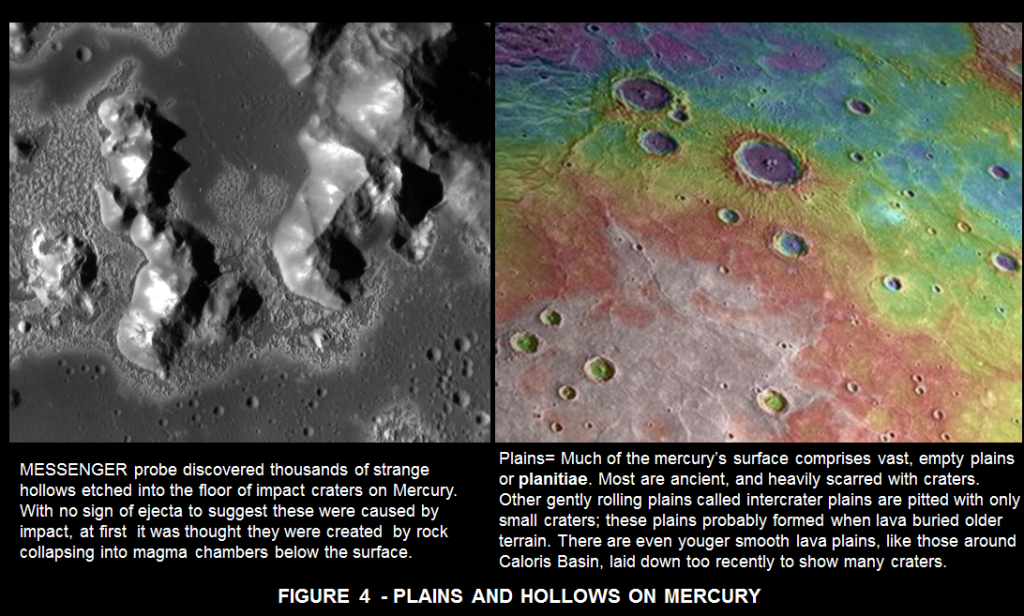

The MESSENGER space probe has photographed volcanic vents around the perimeter of the Caloris Basin, which are evidently the source of these lavas. Mercury’s surface also has several rupes (ridges), which are up to 1-3km high and 500km long. The Messenger probe had also found a high level of volatiles such as sodium (Na) and potassium (K) on the planet’s surface. In places Mercury’s surface is tinged yellow by Sulphur (S). There is more of this element on Mercury than on any other planet in our solar system – it’s about 10 times the amount of sulfur than is found on Earth. Between the craters are vast plains formed by lava flows.

Likewise, on the planet there are hollows . If you could randomly walk around and study the dust and rocks, you might pick up minerals rich in magnesium (Mg) and sulfur (S), similar to a rare type of meteorite formed at high temperatures close to the Sun, just like Mercury. Sometimes, however, you would find deep areas from which the surface has departed into outer space.These hollows are found only on Mercury and are the result of explosive processes, when the soil simply evaporated. Brimstone is sulfur that can become volatile under certain conditions, and sulfur is found in abundance on the planet. This could be to blame for the rapid displacement into outer space of hundreds of square kilometers of soil. Many astronomers think the hollows are scoured out by the solar wind as it vaporizes minerals on the surface. However, there’s still no explanation for the hollows, but there’s a space probe on its way to Mercury that’s sure to help.

Another interesting discovery of late is the possibility that Mercury might be covered with diamonds. Since its crust has a high concentration of carbon in the form of graphite, it is plausible that it also has a large number of diamonds.

Many of the craters on this planet have names, with a total of (only) 402 craters named out of the thousands visible in the images.The naming of Mercury’s surface features follows a system:

- craters are named after artists, composers, and authours – for example, the Tolstoy and Beethoven;

- basins, valleys (valles) are named after observatories;

- cliffs (rupes) after ships;

- ridges (dorsa) after scientists; and

- plains (planitia) take international names for Mercury.

Leave a comment