The Periodic Table of Elements contains 118 elements we currently have knowledge about. 92 of them occur naturally on Earth , all the rest are artificially made.

Most of the 118 elements at normal temperature (20°C) and pressure (1atm), occur in solid state, a few are gases and just 2 are liquid (mercury Hg and Bromine Br). Therefore from obvious reasons we can say that the first state of matter is SOLID. But that’s the case only on Earth, because in the universe, Plasma makes 99,9% of all visible matter. Now, considering the definition of matter as anything that has mass and occupies space, let’s take a closer look at Solids.

WHAT IS A SOLID?

Solid is one of the 3 main states of matter, along with Liquid and Gas. And Matter is the “stuff” of the universe, the atoms, molecules and ions that make up all physical substances.

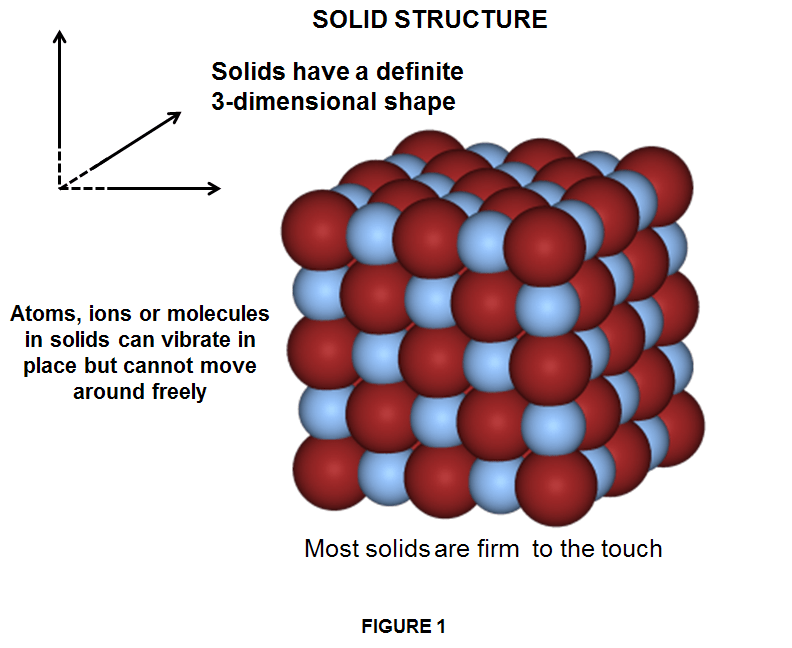

A SOLID is: the most ordered state of matter. Under constant conditions all the constituent particles (atoms, ion or molecules) in the structure of a solid are connected together to form an object with a fixed shape and a fixed volume (although the shape can be altered by applying force).

Almost all elements found in nature on Earth are solids. Solids can hold their shape, and it is because of their unique properties that we can drink coffee in our favorite mug, without the mug changing its shape, or sleep on the bed without the bed turning into a liquid or disappearing into a gas!

In solids, the particles are held together very closely in a regular pattern. The attractive intermolecular forces between individual atoms or molecules in solids are greater than the energy causing them to move apart, hence the atoms cannot move freely within the substance and cannot be compressed into a smaller volume. The molecular motion of particles in a solid is confined only to very small vibrations of the atoms back and forth around their fixed positions. As result, solids have the lowest kinetic energy of all the states of matter. This makes the solids to maintain a certain shape and volume, no matter their container, in opposite like liquids and gases do. Some solids, like sponges, can be squashed but that is because air is squeezed out of pockets in the material – the solid itself does not change size. We can precisely measure solids 3-dimensionaly and we can weight them exactly.

The size of a solid can be known, either in the base dimensional unit a.k.a. meter (m) or in its submultiples (such as centimeter (cm), millimeter (mm), micrometer (µm) etc…) or multiples (such as hectometer (hm), kilometer (km) etc…

The mass of a solid can be preciselly measured in the base unit known as gram (g) or with its submultiples (such as centigram (cg) milligram (mg), microgram (µg) respectivelly multiples such as hectogram (hg), kilogram (kg), megagram or tonne (t) etc…

However, solids encompass a diverse group of materials, and other properties can vary greatly, depending on the exact solid involved. Solids, of course, are not necessarily permanent. Solids are sometimes formed when liquids or gases are cooled; ice is an example of a cooled liquid which has become solid. Also extremely high temperatures can be used to melt solid iron so it can be shaped into a skillet, for example. Once that skillet is formed and cools back to room temperature, though, its shape and size will not change on its own, as opposed to molten metal, which can be made to drip and change shape by gravity and molds. The same is true for ice cubes that are kept in the freezer: Once they are formed, their size and shape doesn’t change.

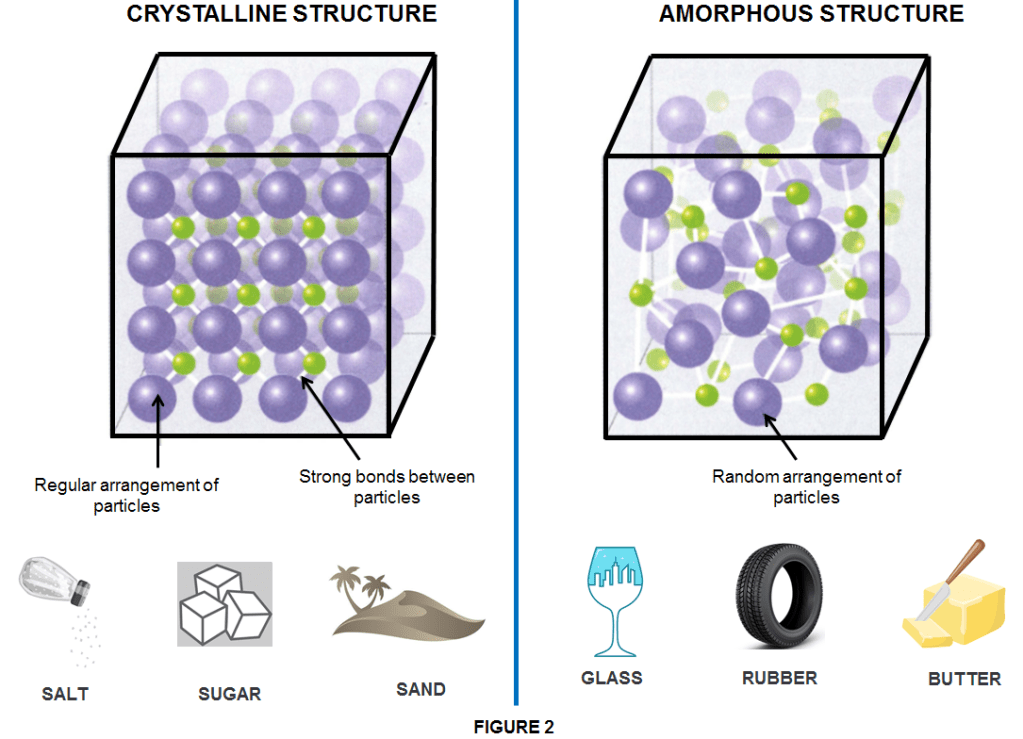

Based on how the constituent particles in their structure are arranged, the solids occur in 2 main types:

- crystalline solids

- non-crystalline (amorphous) solids.

Crystalline solids are particles with a well-organized pattern and shape, such as a 3D structure in which all bonds between particles have equal strength. Therefore the resulted solid has a distinct melting point.

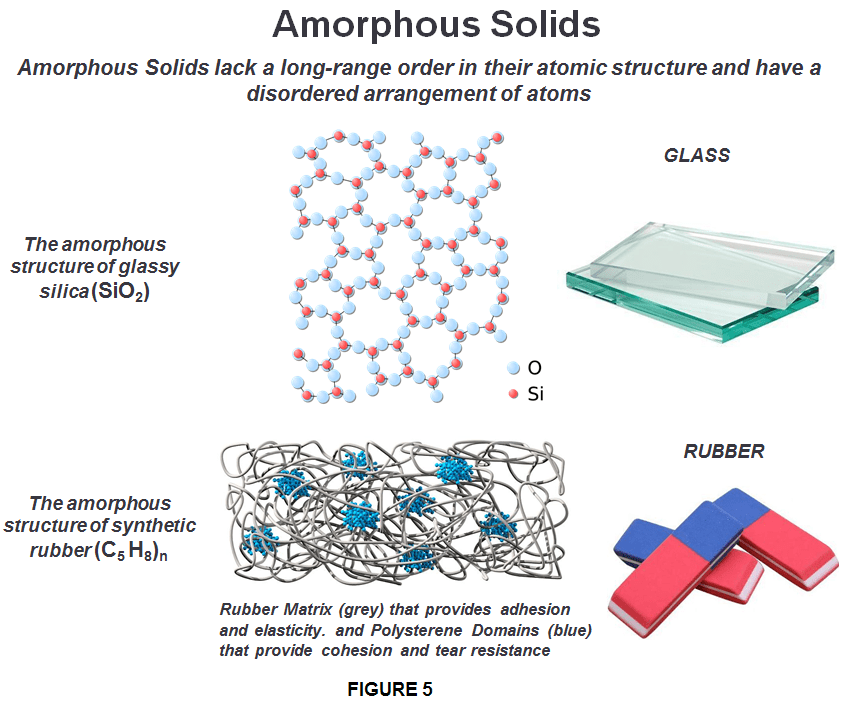

Amorphous solids are particles that have random arrangements, so they lack an organized shape and/or pattern and melt over a range of temperatures.

Solids are placed into their corresponding category based on differences in the type of particle (ion, atom, or molecules) and the type of attractive force present.The materials present and the conditions in which a solid is created dictate whether it will be a crystalline or amorphous solid

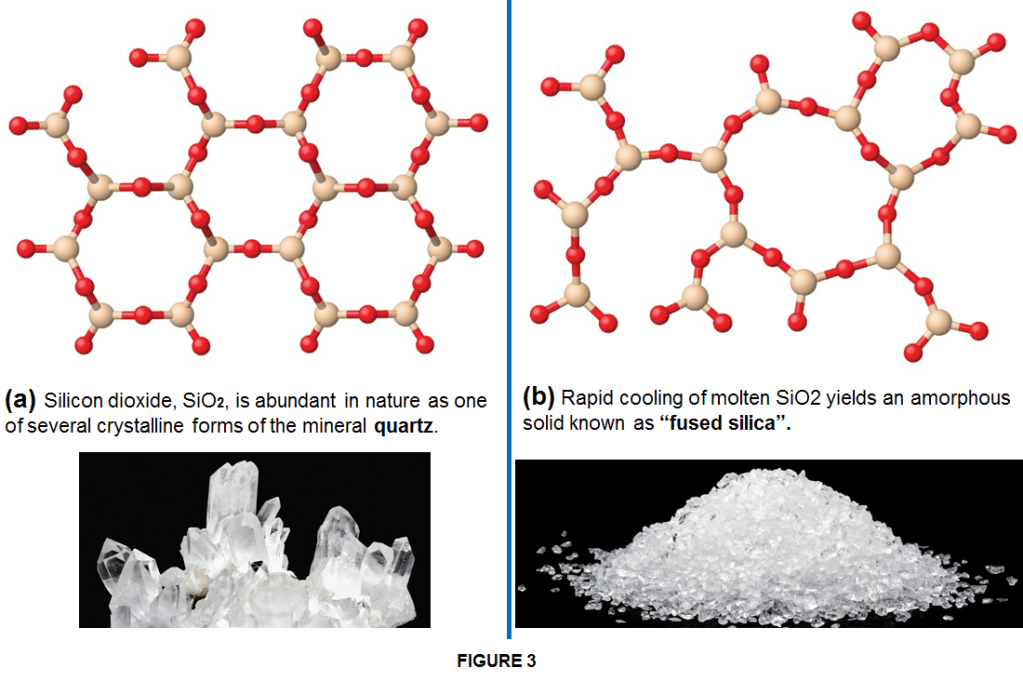

Usually, when conditions are steady (such as slow and gradual cooling/heating), the particles have a chance to align uniformly becoming crystalline such as for instance sugar. However, when there are extreme and rapid temperature changes, an indefinitely shaped solid will most likely be the result and the solid is an amorphous one such as glass. In an other case when solids are formed by a long chain of molecules they become polymeric solids such as rubber or plastics which often have mixed areas in their structure including both amorphous and crystalline phases. For examples, candle waxes are amorphous solids composed of large hydrocarbon molecules. Some substances, such as silicon dioxide, can form either crystalline (as quatz or sand) or amorphous solids (as glass or fused silica) too (as shown in Figure 3), depending on the conditions under which it is produced.

Also, amorphous solids may undergo a transition to the crystalline state under appropriate conditions. There is no solid which is 100% crystalline or 100% amorphous. In their structure solids always contain more or less both of these types of structures.

A particular case are Polimeric Solids. In these solids the molecules form long chains which may contain anything between 1000 and 10000 molecules. Many are natural organic materials such as plant constituents but there are many synthetic polymers, one example being polythene. The precise properties of the polymer depend on just how tightly these chains of molecules are bound together. They may be tangled together in a haphazard way or lie side by side. Any cross- chain linking will enormously increase the strength of the material and the vulcanising of rubber, for example, eventually produces the hard crystalize material ebonite:this is the result of cross- chain linking by sulphur atoms.

Below a critical temperature polymers behave much like glass (but with a greater degree of ductility) but above it they are more rubber-like, therefore they become amorphous. Cooling rubber in liquid nitrogen strikingly illustrates this change of properties.

CRYSTALLINE SOLIDS

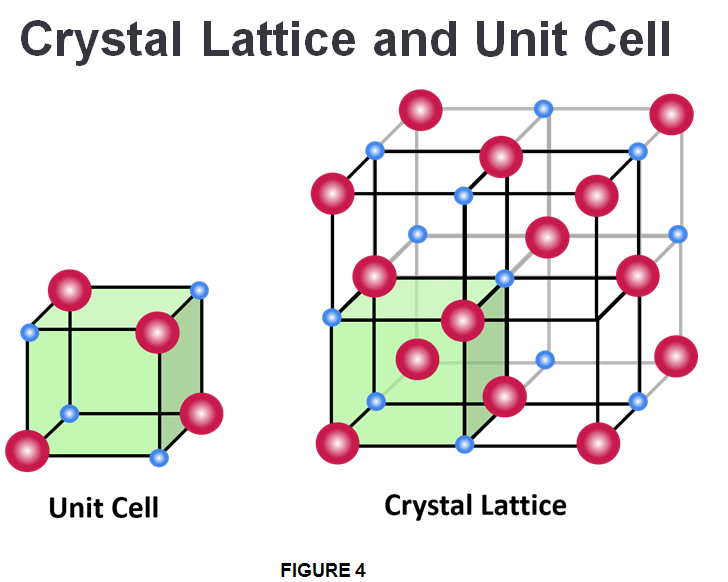

Crystalline solids, or crystals, are regarded as “true solids.” In crystalline solids, the atoms, ions or molecules are arranged in an ordered and symmetrical pattern that is repeated over the entire crystal. The smallest repeating structure of a solid is called a unit cell, which is like a brick in a wall. In turn, the unit cells combine to form a 3D network called a crystal lattice. Most minerals are crystalline solids. Common table salt (NaCl) is one example of this kind of solid as well. Some substances, such as diamond (a crystalline pattern form of carbon), form one large crystal. However, most are made up of lots of smaller crystals.

Just for reference there are 14 different basic types of such structural arrangements in crystalls also known as Bravais lattices, but this is a topic for another article. For now let’s just review what crystalline solids are.

In Fig.4 the blue and red dots seen in the lattice corners represents a lattice point and consists of a specific atom, molecule, or ion. Aside from the regular arrangement of particles, crystalline solids have several other characteristic properties. They are generally incompressible, meaning they cannot be compressed into smaller shapes. Because of the repeating geometric structure of the crystal, all the bonds between the particles have equal strength. This means that a crystalline solid will have a distinct melting point, because by applying heat, it will break all the bonds at the same time.

Most crystalline solids exhibit anisotropy. This means that properties such as refractive index (how much light bends when passing through the substance), conductivity (how well it conducts electricity) and tensile strength (the force required to break it apart) will vary depending on the direction from which a force is applied. Crystalline solids also exhibit cleavage; when broken apart, the pieces will have planed surfaces, or straight edges.

Generally this type of solids (n. : crystalline) are classified according the nature of the forces that hold the particles together. These forces are primarily responsible for the physical properties exhibited by the bulk solids. Crystal structure determines a lot more about a solid than simply how it breaks. Structure is directly related to a number of important properties, including, for example, conductivity and density, among others. Without getting to much in details to explain these relationships, I just mention that there are 4 main types of crystalline solids, namely:

- COVALENT NETWORK SOLIDS;

- IONIC SOLIDS;

- MOLECULAR SOLIDS;

- METALLIC SOLIDS;

NOTE: These 4 sub-types of solids are typically the cases for crystalline versions, yet under certain conditions these categories also occur as amorphous versions.

AMORPHOUS SOLIDS

In amorphous solids, the smallest unit can be an ion, atoms, molecules, or even polymers yet unlike in crystalline solids, the atoms or molecules that make up amorphous solids are not arranged in a regular pattern. Instead they are arranged more like those in a liquid, although they are unable to move around.

In amorphous solids (literally “solids without form”), the electrostatic forces present in amorphous solids can vary. That’s why they are also called “pseudo solids.” Amorphous solids are often formed when atoms and molecules are frozen in place before they have a chance to reach the crystalline arrangement, which would otherwise be the preferred structure because it is energetically favored. One important consequence of the irregular structure of amorphous solids is that they don’t always behave consistently or uniformly. For example, they may melt over a wide range of temperatures, in contrast to a crystalline solid’s very precise melting point. An amorphous solid melts gradually over a range of temperatures, because the bonds do not break all at once. This means an amorphous solid will melt into a soft, malleable state (think candle wax or molten glass) before turning completely into a liquid. In addition, amorphous solids have no characteristic symmetry so they break unpredictably and produce fragments with irregular, often curved surfaces, while crystalline solids break along specific planes and at specific angles defined by the crystal’s geometry.

Amorphous solids are isotropic — that is, their physical properties are the same in whichever direction they are measured. For example properties such as refractive index, thermal and electrical conductivity and tensile strength are equal regardless of the direction in which a energy is applied. An amorphous material has the density of a solid but the internal structure of a liquid, although one with an enormously great viscosity, glass, plastic and soot are such examples. They are considered to be super-cooled liquids in which the molecules are arranged in a random manner similar to that of the liquid state. Examples of amorphous solids include glass, rubber, gels and most plastics.

Leave a comment