At first glance aerogel resembles a hologram. It’s deceiving whether it’s really there or not. A highly porous solid material, aerogel has the lowest density of any solid materials known to man. It is 1000 times less dense than glass, aerogel has earned the nickname “solid blue smoke”.

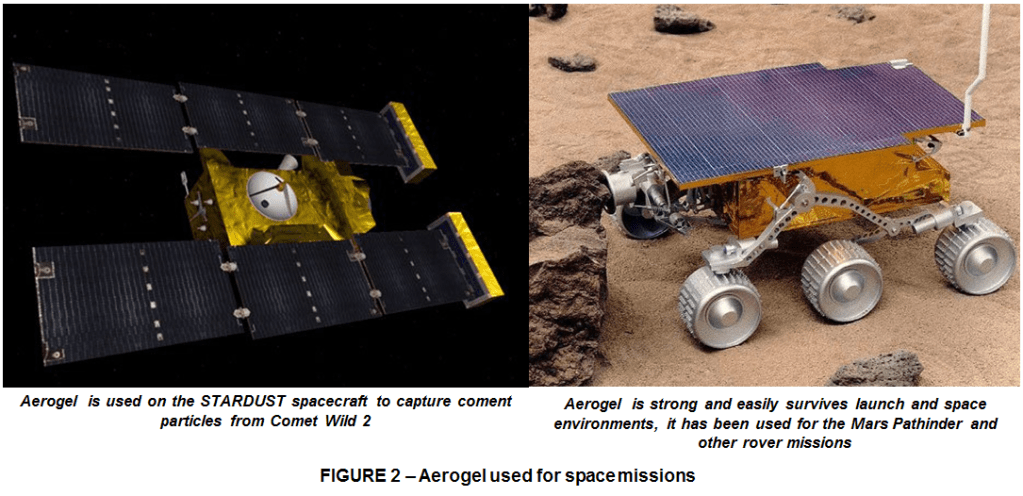

At the time in the early 1980s, aerogels were so expensive to make that they could only live in labs where money was no object. The CERN lab was one of the 1st aerogel producer and NASA followed soon. The first applications of silica aerogels in space exploration were to insulate electronic equipment from extreme (cold or hot) temperatures. Aerogels are particularly suitable for this application because not only are they the best insulators in the world, but they are also extremely light and when you’re launching a spacecraft out of the gravitational pull of the Earth, reducing weight matters rather a lot.

The “silica aerogel” is known today as one of the lightest solid in the world and it was a material kept secret in until late in 1990s by the US labs which later on started to be widely used by NASA for its space exploration projects. The most important breakthrough happened on 2nd of January 2004 when the TV news announced that the NASA mission to capture stardust had successfully engaged with comet Wild 2. The news programme then showed a picture of a new material that turned out to be a substance known as aerogel. This was the material used to collect the stardust.

But actually the Aerogel was used first in 1997 on the Mars Pathfinder mission and has been used as an insulator on spacecrafts ever since. But once the scientists at NASA found that aerogel could cope with space travel they realized that the material had another possible use. If you look up into the sky on a clear night you might see a shooting star, which appears as a bright trail of light crossing the sky. For a long time it has been known that these are meteors which enter the Earth’s atmosphere at high speeds and burn brightly as they heat up. It is thought that most of these are space dust, which is leftover material from the creation of the Solar System 4,5 billion years ago, along with comets and other asteroids.

Determining exactly what materials these heavenly bodies are made has been of interest for many years, since this information could help us understand how the Solar System was formed and may also account for the chemical composition of the Earth. Analyzing the material composition of meteorites has given us some tantalizing clues, but the problem with these specimens is that they have all been heated to extremely high temperatures by their passage through the atmosphere. So the question was: Wouldn’t it be nice, the people at NASA thought, if they could capture some of these objects out in Space and bring them back to Earth in a pristine state?

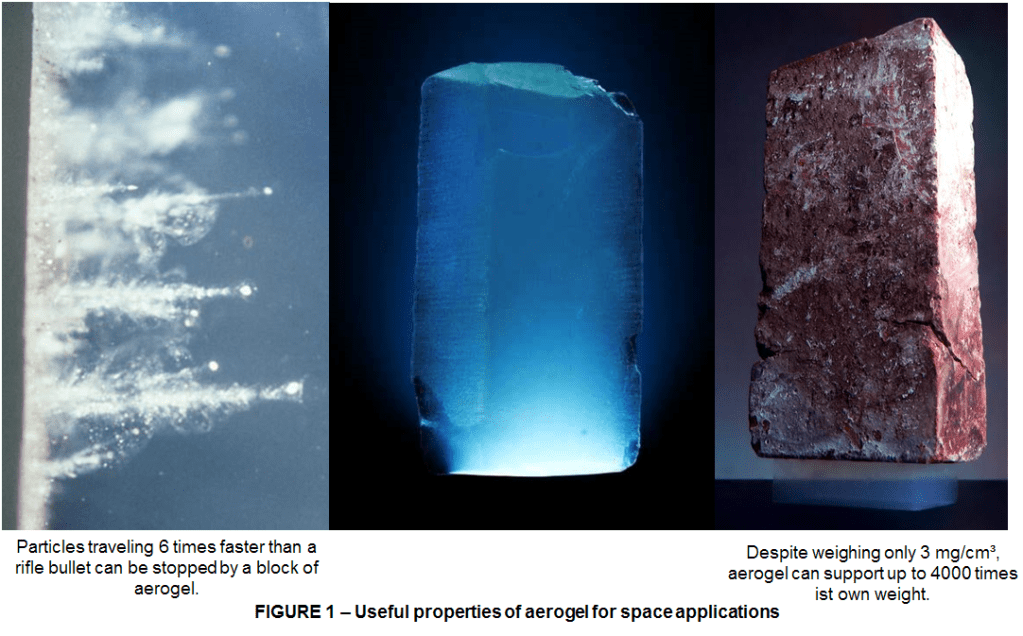

The first problem with this idea is that objects in Space tend to be traveling rather fast. Space dust is often going at speeds of 50 kilometers per second, which equates to 180,000 kilometers per hour, a lot faster than a bullet. Catching an object like that is not easy. As with stopping a bullet with, say, your body either the force of the bullet exceeds the rupture pressure of your skin, meaning it goes through you, or you employ a bulletproof vest made of a high rupture strength material, such as Kevlar, which results in a compressed and deformed bullet. Either way, it’s a risky business.

However, in principle, it is quite possible – just as when catching a cricket ball or baseball with “soft” hands, the trick is to spread and dissipate the ball´s energy rather than bracing yourself for a single, high-pressure impact. What NASA needed, then, was a way to slow the dust down from 180,000 km/hour to zero without damaging the dust or the spacecraft – ideally a material with a very low density, so that the dust particles would be slowed gently without being damaged; ideally one that could do so within the space of a few millimeters; and ideally one that would be transparent, so that scientists could find the tiny specks of dust once they were buried in it. That such a material existed was a minor miracle. That NASA had already used it in space flights was extraordinary. It was, of course, silica aerogel.

The mechanism by which aerogel pulls off this feat is the same as the one used to protect stunt actors in movies when they fall off tall buildings: a mountain of cardboard boxes, each box absorbing some of the energy of the impact as it collapses beneath the actor’s weight, and the more boxes, the better. In the same way, each foam wall within aerogel absorbs a tiny amount of energy when it is struck by the dust particle, but since there are billions of them per cubic centimetre, there are enough of them to bring it to a halt relatively unharmed. NASA built an entire space mission around the ability of aerogel to gently collect stardust.

On 7 February 1999, the Starcecraft Stardust was launched, containing all of the equipment necessary to take a trip through the Solar System, while also being programmed to by past a comet called Wild 2. The idea was that it would collect interstellar dust from deep space as well as the dust being ejected from a comet, allowing NASA to study the material composition of both. In order to do this, they developed a tool that resembled a giant tennis racquet, but instead of holes between the strings there was aerogel.

So the particles were travelling about 6km/s relative to aerogel, so when they hit the aerogel , because the aerogel’s a very low density material, very, very porous material, the particles actually enter the aerogel and as they travel through the aerogel, they basically break apart the network that makes up the aerogel and they lose energy in the process and eventually come to a stop. This is good for capturing particles, because if a particle like that were to hit a solid surface, then it just stops, you know immediately and vaporizes.

During the summer and autumn of 2002, while in deep space, millions of kilometers from any planet, the Stardust spacecraft opened a hatch and poked out its giant tennis racquet fitted with aerogel. It had no opponent in this game of interstellar tennis and the balls it was looking for were microscopically small: the remains of other stars long gone, the leftover ingredients of our own Solar System still flying around. The Stardust spacecraft couldn´t hang around in deep space too long because it had an appointment to keep with the comet Wild 2 now hurtling from the outer reaches of the Solar System and approaching the center, which it does every 6.5 years. Having withdrawn its aerogel tennis racquet, the spacecraft sped off for its meeting. It took over a year to get to the right position, but on 2 January 2004 the spacecraft found itself on a collision course with comet, which was 5 kilometers in diameter and speeding off around the sun. Once it had maneuvered itself into the slipstream of the comet, 237 km behind it, the spacecraft opened its hatch and once again poked out its aerogel tennis racquet, this time using the B-side, and started to collect, for the first time in human history, virgin comet dust. Having collected the comet dust, the Stardust spacecraft returned to Earth, arriving back 2 years later.

As it approached the Earth it veered away, jettisoning a small capsule, which fell under Earth’s gravity, entering the atmosphere at a speed of 12.9 km/s, the fastest re-entry speed ever recorded, and so becoming for a while a shooting star itself. After 15 seconds of free-fall, and having reached red-hot temperatures, the capsule deployed a drogue parachute to slow down the rate of descent. A few minutes later, at a height of 3km above the Utah desert, the capsule jettisoned the drogue chute and deployed the main parachute. At this point the recovery crews on the ground had a good idea of where the capsule was going to land and headed out into the desert to welcome it back from its 7-year, 4-billion-kilometre round trip. The capsule hit the sand of the Utah desert at 10.12 GMT on Sunday, 15 January 2006.

However, until they opened the capsule and started examining the aerogel samples scientists had no idea whether they held any answers to anything. Perhaps the space dust would have passed straight through the aerogel. Or perhaps the violence and deceleration of re-entry would have disintegrated the aerogel into meaningless powder. Or perhaps there would be no dust at all. They need not have worried. Once they got the capsule back to the NASA laboratories and opened it up, they found that the aerogel was fully intact and almost completely perfect. There were minuscule puncture marks in the surface and it was these that were subsequently shown to be the entry points for the space dust. Aerogel had done the job that no other material could do: it had brought back pristine samples of dust from a comet formed before the Earth even existed.

Since the return of the aerogel capsule, it has taken NASA’s scientists many years to find the tiny pieces of dust embedded within the aerogel, and the work continues to this day. The dust they are looking for is invisible to the naked eye, and so it must be found by microscopic examination of the samples, which has taken years. The project is so massive that NASA has enlisted the public to help with the search. The scheme Stardust@Home trains volunteers to use their home computers to look through thousands of microscopic images of the aerogel samples and try to spot the signs that a piece of space dust is present. The work so far has thrown up a number of interesting results the most surprising of which is that most of the dust from the comet Wild 2 shows the presence of aluminium-rich melt droplets. It’s very hard to understand how these compounds could have formed in a comet that had only ever experienced the icy conditions of Space, since they require temperatures of more than 12000 °C to do so. Since comets are thought to be frozen rocks that date back to the birth of the Solar System, this has come as a bit of a surprise to say the least. The results seem to indicate that the standard model of comet formation is wrong, or there is a lot more we don’t understand about how our Solar System formed.

Meanwhile, having completed its mission the Stardust spacecraft has now run out of onboard fuel. On 24 March 2011, when it was 312 million kilometres away from Earth, it responded to a final command from NASA to shut down communications. It acknowledged this command, and said its final goodbye. It is currently travelling off into deep space, a kind of man-made comet.

So should we expect to see aerogel in our everyday lives anytime soon? I have already good reasons to believe, YES we should.

Leave a comment