At most workplaces one of the common mindset the management team has, it that “The best business plan wins”.Therefore in case something goes wrong or not quite according to the plan they always complain that the “plan was not the best”.

Ok, then let me ask: Why the business world is ruled by so many incompetent people which are easily promoted in management position without having done anything remarkable, except the fact they were just in some favorable circumstances?

Does The Best Plan Always Wins? Absolutely not. The more in detail you plan, the more in detail you’ll fail. The level of details you put in that plan, is equivalent with the level of how deep you go in trouble afterwards. You don’t need to waste your time trying to plan something in too much details which in almost 100% of cases it won’t happen as foreseen anyway.

The movie “Mission Impossible” with Tom Cruise is a very good analogy with the real life, showing us how the best plan actually fails. You may have noticed that the title of this movie is “Mission Impossible” for a reason. In fact, what Tom Cruise is doing, it turns to be “Mission Possible”.

In the movie the flow of actions are very diverse and the suspense is always there, showing that everything which was well planned in advance didn’t truly happen as expected. Instead Tom had to deal with all sort of difficult situations which he all the time make them turn in his favor, but not because he planned to be like that, but because he played his role perfectly and his intelligence made him succeed without planning anything in advance at all. He had good fellows around him and they trusted in each other. But this is in the movie, in real life the opposite is happening. So as we talk about work, let’s put this in the context of working in an organization. Comparing the “Mission Impossible” movie scenario with daily background at workplaces, exactly the opposite is happening.

If you’ve recently been promoted to team leader, the first thing you’ll be expected to do is create a plan. You’ll be asked – before you even start, most likely – what your plan is for your team, or, more specifically, what your 90 day plan is for your team?You’ll have to sit down, think hard, survey your team members (many of whom you will have inherited), and then do your best Tom Cruise impression and make your plan. You’ll be most probably asked to do the following 6 settings:

- Expand the teams capabilities

- Create a team identity

- Anticipate & influence change

- Inspire the team towards higher levels of performance

- Enable & empower group members to accomplish their work

- Encourage team members to eliminate low-value work

And when you do this: you’ll quickly realize one of the many differences between your team and Cruise’s: his team works alone, while yours appears to be connected to a whole host of other teams, each with their own version of the plan. In fact, poke your head above the parapet of your team for a second and look out across all the other teams in the company, and you’ll discover something of a planning frenzy. Every team is about to go, or is away on, or is just back from, or is just debriefing from, their off-site, during which they formulated, or perhaps reformulated, their current version of the plan.

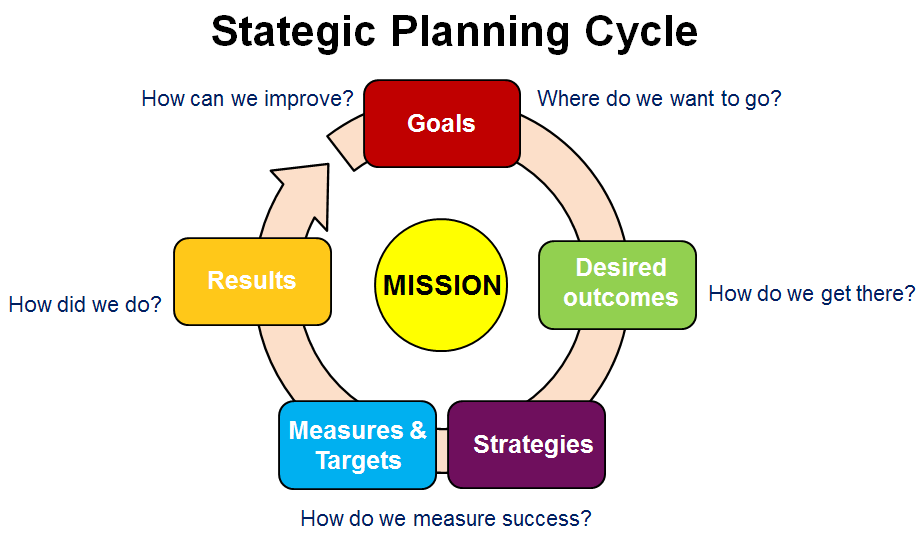

It won’t be immediately obvious to you, but after a few years you’ll discern that there is a pattern to this planning, a predictable rhythm that repeats itself year after year: in September, in advance of the November board meeting, the leaders of your company will go away on a senior leadership retreat. They may do a SWOT analysis (Strengths/Weaknesses/Opportunities/Threats – and it’s just as fun as it sounds); they may bring in outside consultants to help them; and after much analysis and debate and proposal and counter-proposal, the white smoke will emerge from the chimney, and the leaders will emerge with: THE STRATEGIC PLAN

They will then present this plan to the board, and once it’s approved, they will share it with their direct reports. This plan will then be sliced up into many other plans (departmental plans, divisional plans, geographic plans, and so on), each slice-finer and more detailed than the preceding one, until you, too, are asked to take your team off – site and construct your version of the plan.

We do this because we believe that plans are important. If we could just get the plan right, we think, and weave every team’s plan into the broader company plan, then we could be confident that our resources were allocated appropriately, that the correct sequence and timing were laid out, that each person’s role was clearly defined, and that we had enough of the right people to fill each required role. Buoyed by this confidence, we’d know that we’d only have to galvanize our teams to give their all, and success would follow. At the same time, there is a yearning quality to all this planning. We are attempting to shape our future, and our plans can feel like scaffolding stretching out into the months ahead, upon which we’ll build our better world – their function is perhaps as much to reassure us as it is to make that world real. Plans give us certainty, or at least a bulwark against uncertainty. They help us believe that we will, indeed, walk out of the casino with the cash.

And yet, just as this cycle of big plans leading to medium plans leading to small plans is familiar to you, so – surely – is the nagging realization that things rarely, if ever, turn out the way you hope they will. Sure, planning is exciting in the beginning, but the more you sit in all these planning meetings, the more a feeling of futility creeps in. While it all looks great on paper, tidy and perfect, you sense it’s never really going to play out like this, and that as a result you’ll soon be back in yet another planning meeting. You’ll leave this one with the broad contours of your plan sketched out, and you’ll agree on the next steps necessary to refine those contours into something specific and actionable, and then the meeting to make things actionable will get postponed a bit, and then, when it finally happens, it will drift off in another direction. And then, when your team finally gets around to nailing the details, some new idea or thought or realization will emerge that leads you to rethink what you started off with. Tom Cruise never had to deal with this. But in the real world you’ll have to. The defining characteristic of our reality today is its ephemerality – the speed of change. There are at least 6 important criteria you have to consider as follows:

- Urgency

- Degree of support

- Amount and complexity of change

- Competitive environment

- Knowledge and skills available

- Financial and other resources.

Everywhere we look we see this speed of change. When you put your plan together in September, it’s obsolete by November. And if you look at it in January, you might not even recognize the roles and action items you wrote out in the fall. Events and changes are happening faster than they ever have before, so dissecting a situation and turning it into a meticulously constructed plan is an exercise in engaging in a present that will soon be gone. The amounts of time and energy it takes to make a plan this thorough and detailed are the very things that doom it to obsolescence. The thing we call planning doesn’t tell you where to go; it just helps you understand where you are. Or rather, were. Recently. We aren’t planning for the future, we’re planning for the near-term past.

And where are the people who are making the plan? So far behind the front lines of the company that they don’t have enough real-world information upon which to make the plan in the first place. How can you make a plan to sell a particular sort of product to a particular sort of customer when you’re not out selling every day? You can’t, not really. You can make a theoretical sales “model” based on your conceptual understanding of an abstract situation, or on an averaged data set that summarizes trends. But if it’s not grounded in the real-world details of each actual sales conversation-when do the prospects’ eyes glaze over, when do the prospects lean forward, when do they start to finish your sentences-your plan will always be more assumptive than prescriptive.

Your people want and need to engage with the world that they’re really in, and to interact with the world as it really is. By harnessing them to a prefabricated plan, you’re not only constraining your people but, quite possibly, also revealing how out of touch with reality you are. This is not to say that planning is utterly useless. Creating space to think through all of the information you have in your world, and trying to pull that into some sort of order or understanding, has some value. But when you do that, know that all you’ve done is understand the scale and nature of the challenges your team is facing. You’ll have learned little about what to do to make things better. The solutions can be found in the tangible and changing realities of the world as it really is, whereas your plans are necessarily abstract understandings of the recent past. Plans scope the problem, not the solution.

So, though you are told that the best plan wins, the reality is quite different. Many plans, particularly those created in large organizations, are overly generalized, quickly obsolete, and frustrating to those asked to execute them. It’s far better to coordinate your team’s efforts in real time, relying heavily on the informed, detailed intelligence of each unique team member.If you move information across an organization as fast as possible, and do so to empower you will get a immediate and responsive action. Underlying the assumption that people are wise, and that if you can present them with accurate, real time, reliable data about the real world in front of them, they’ll invariably make smart decisions.It’s not true that the best plan wins. It is true that the best intelligence wins.

“Talent wins games, but team work and intelligence wins championships” – Michael Jordan

Leave a comment