In corporate world, regardless the industry and the job you have ,your boss will always set goals for you. That’s a fact. These companies take “cascading goals” as equivalent with being successful.Translated in reality, I mean for regular employees, none of these are of any importance. People don’t need to receive a set goals for their work, they need to understand the meaning of their work. Goal at workplace are equally useless as the feedback at workplace. Unfortunately in the majority of companies/organization they still advocate this idea that people must have “a set of goals” for their work. Due to this wide-spread concept between big corporation, it seems to be general accepted that in order to be successful in business , it’s necessary to cascade goals. But again, That’s a completelly false assumption. No, goals are not necessary to be set or cascaded at all. And above that, it is completely useless to evaluate someone’s performance strictly based on how much of his/her imposed goals have been reached at the end of the fiscal year. What companies must cascade instead is MEANING.

Goals are everywhere at work – it’s hard to find many companies that do not engage in some sort of annual or semi-annual goal-setting regimen. At some point in the year, usually at the start of a fiscal year or after bonuses and raises have been paid, the organization’s senior leaders set their goals for the upcoming 6 or 12 months, and then share them with their teams. Each team member looks at each of the leader’s goals, and figures out what to do to advance that goal, and thus sets a sort of minigoal that reflects some part of the leader’s goal. This continues down the chain, until you, and every other employee, has a set of goals that are miniversions of some larger goal further up in the organization. In some organizations, goals are also grouped into categories, so that each person is asked to set, say: strategic goals, operational goals, people goals, and innovation goals.

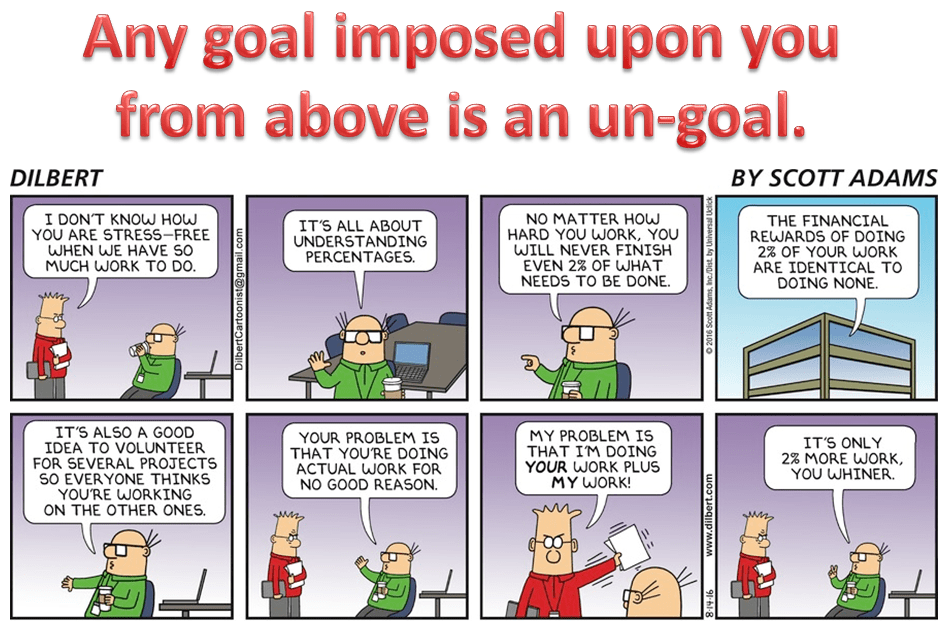

Once the goals have been created, each is then approved by the person’s immediate leader, and then by the leader above that person, and so on, with each layer assessing whether each goal is sufficiently challenging, and whether it’s properly aligned with the goals above, up and up and up the chain. As the year unfolds, you may well be asked to record what percentage of your goals you’ve completed. This “percent complete” data is then aggregated into bigger and bigger groups so that the company can, at any point during the year, say things like, “65 % of our teams have completed 46 % of their goals. We need to speed up!”

And, at the end of the year, you’re asked to write a brief self-assessment reflecting how you feel you’ve done on each goal, after which your team leader will review this assessment and add his own, in some cases also saying whether he thinks each goal was actually met, or not. After HR has nudged him a couple of times, he’ll input all this information into the company performance management system, where upon it’ll serve as a permanent record of your performance for the year, and will guide your pay, promotion opportunities, and even continued employment.

If you’re in sales for example, your sales quota will work in a similar way – an overall corporate sales goal is sliced into parts and distributed across the organization. The only difference being that your quota, or your team’s quota, is usually just a single number handed down to you from above, defining you and your work throughout the year – which is why salespeople, in most companies, are referred to not as people but simply as “quota carriers.”

The names we give these goals have changed over the years. It started with MBOs, (Management by Objectives). Then came SMART goals, (goals that are: Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Realistic, and Time-bound), followed shortly by KPIs (Key Performance Indicators). The latest incarnation, OKRs (Objectives and Key Results), originated at Intel and is now used for defining and tracking goals and measuring them against your “key results.” Across all the different technologies and methodologies, massive amounts of time and money are invested in this goal-setting. When companies like these shell out close to €1 billion on something every year, there must be some truly extraordinary benefits. What are they?

Well, every company is different, of course, and each makes its own calculus, but the three most common reasons put forth for all this goal-setting are:

- The 1st = that goals stimulate and coordinate performance by aligning everyone’s work;

- The 2nd = that tracking goals’ “percent complete” yields valuable data on the team’s or company’s progress throughout the year;

- The 3rd = that goal attainment allows companies to evaluate team members’ performance at the end of the year.

So, companies invest in goals because goals are seen as a stimulator, a tracker, and an evaluator – and these three core functions of goals are why we spend so much time, energy, and money on them. And this is precisely where the trouble begins. In terms of goals as a simulator of performance, one great fear of senior leaders is that the work of their people is misaligned, and that effort is being wasted in activities that drag the company hither and yon, like a rudderless boat in a choppy sea. The creation of a cascade of goals calms this fear, and gives leaders the confidence that everyone on the boat is pulling on the oars in the same direction. Of course, none of this alignment is worth very much, if the goals themselves don’t result in greater activity – if the boat doesn’t actually go anywhere. As it happens, no research exists showing that goals set for you from above stimulate you to greater productivity. In fact, the weight of evidence suggests that cascaded goals do the opposite: they limit performance. They slow your boat down.

Alright then, but, what about evaluating employees? Can we evaluate a person based on how many goals he or she has achieved? Many companies do this, for sure. But here’s the snag: unless we can standardize the difficulty of each person’s goals it’s impossible to objectively judge the relative performance of each employee.

Let’s say we have two employees we’re evaluating, Sarah and Albert. Each is aiming to complete five goals, and at year’s end Sarah has achieved three goals and Albert has achieved five. Does that mean Albert is a higher performer? Not necessarily. Maybe one of Sarah’s five goals was “Govern an empire” and one of Albert’s five goals was “Make a cup of tea.” For us to use goal attainment to evaluate Sarah and Albert, we need to be able to perfectly calibrate each and every goal for difficulty – we need each manager, with perfect consistency, to be able to weigh the stretchiness or slackness of a given goal in exactly the same way as every other manager. And as it happens this sort of calibration is a practical impossibility, so we can’t. Sorry, Albert.

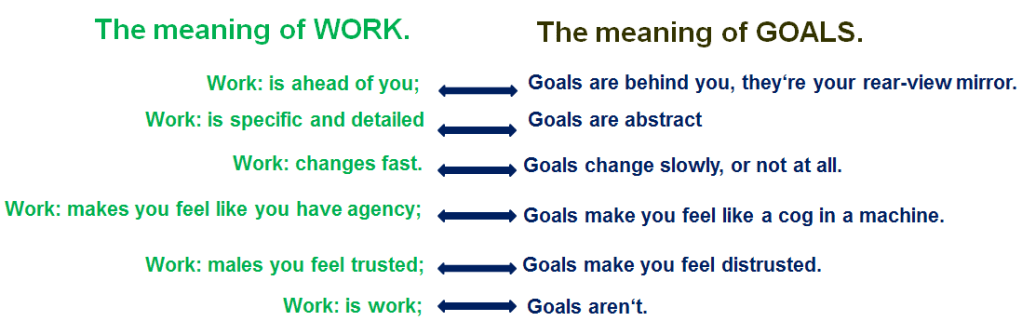

Despite this evidence, however, it remains true that goals, and cascaded goals in particular, have an intuitive appeal to many leaders who find themselves in search of ways to ensure efficient and aligned execution in their organizations. And, at the same time, it also remains true that for those of us in the trenches, our experience of goals feels non-intuitive, mechanical, fake, even demeaning. Why is that?

Well, in the real world, this is what’s going on. Firstly, and oddly, when you sit down to write your goals, you already have a pretty good idea of the work that you’re about to do. After all, it’s not as though you roll up to the office on a Monday morning desperately trying to figure out how you’re going to fill the time. So what the goal-setting process is asking you to do is to write down work that you already know you’re going to do. Your work goals aren’t out ahead of you, pulling you along like our marathoner’s goal; instead they’re just behind you, being tugged along by your own preexisting understanding of the work you’re going to do anyway.

The goal categories – strategic, operational, innovation, people, and so on – are odd simply because work doesn’t come in categories. You don’t plan your time by thinking, “Well, on Tuesday I’ll do some operational, and hopefully make time for a bit of innovation on Thursday afternoon.” Work usually comes in projects, with deadlines and deliverables, and so when you’re asked to translate it back into category goals, you (and most every other employee) fudge it and force – fit your work to the categories, while hoping no one will mind too much.

And while it’s not unreasonable to hope that the work you do matches up to what your team leader wants you to do, setting goals that are a subset of his goals, or reviewing your goals against his, is actually a pretty strange way of going about this. Your team leader already knows what you’re doing, because in the real world you talk to him about it, all the time. If you’re off working on origami and he’d rather you were working on quilting, he’ll tell you. And when something changes, a few days later, and he needs you to shift your focus over to glass-blowing, again, he’ll just tell you. Even if he doesn’t tell you, and you continue to potter away at something that’s all of a sudden out of whack, the very last thing he’d think of doing to communicate this to you is to go back into your goal form, change your goals, and hope you’ll notice.

In the real world, there is work-stuff that you have to get done. In theory world, there are goals.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Goals can be a force for good.

This doesn’t mean, though, that there is nothing we should cascade in our organizations. Since goals, done properly, are only and always an expression of what a person finds most meaningful, then to create alignment in our company we should do everything we can to ensure that everyone in the company understands what matters most.

So, in addition to giving our teams and their members a real-time understanding of what is happening in the world, we need to give them a sense of which hill we’re trying to take. Instead of cascading goals, instead of cascading instructions for actions, we should cascade meaning and purpose.Whereas cascaded goals are a control mechanism, cascaded meaning is a release mechanism. It brings to life the context within which everyone works, but it leaves the locus of control – for choosing, deciding, prioritizing, goal setting – where it truly resides, and where understanding of the world and the ability to do something about it intersect: with the team member.

Therefore the prevailing assumption is that we need goals because our deficit at work is a deficit of aligned action. We’re mistaken. What we face instead is a deficit of meaning, of a clear and detailed understanding of the purpose of our work, and of the values we should honor in deciding how to get it done.

PEOPLE DON’T NEED TO BE TOLD WHAT TO DO; THEY WANT TO BE TOLD WHY.

Greetings! Very helpful advice within this post! It is the little changes that produce the largest changes. Thanks for sharing!

LikeLike

You’re welcome 🙂 I’m glad to hear you find my post helpful.

LikeLike

If we have to set goals like “Govern an Empire” or “Make a cup of tea”, we are bound to fail. Making such silly and foolish targets are against professional working. As you rightly pointed out, the measure of employee engagement, actual performance and its assessment will depend on how diligently we set the goals.

LikeLike